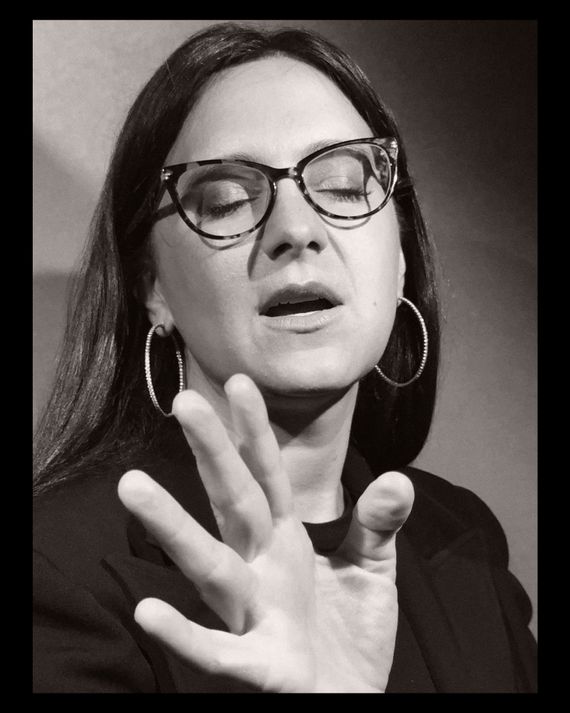

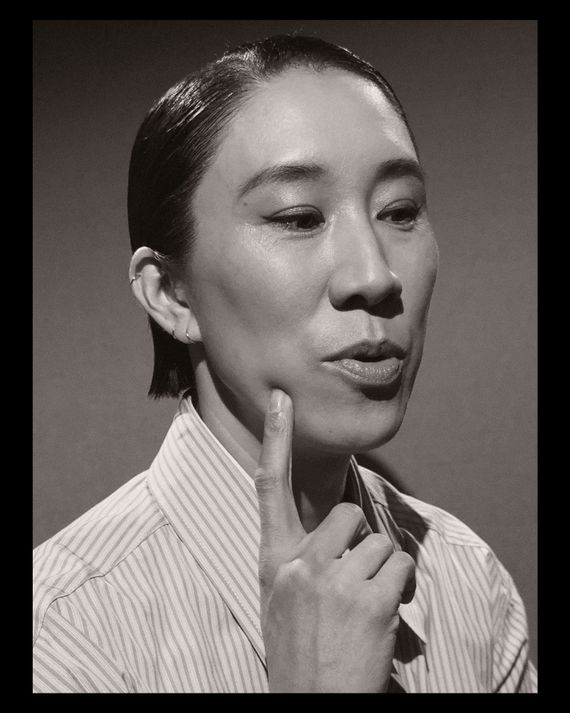

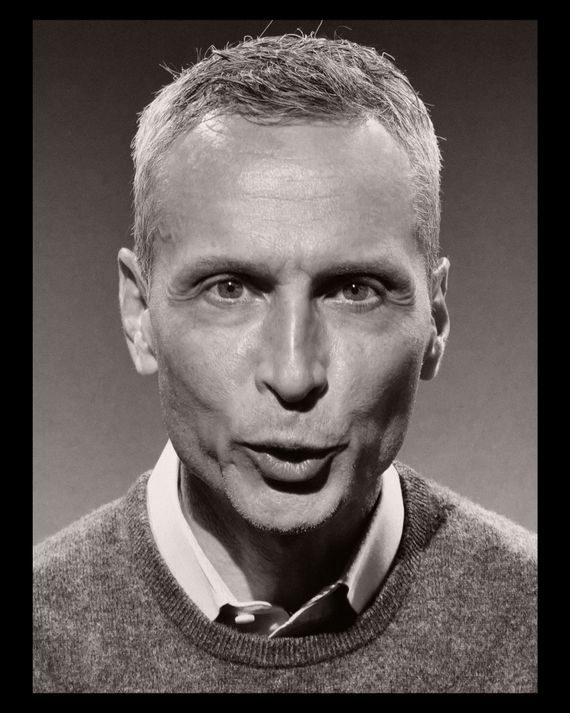

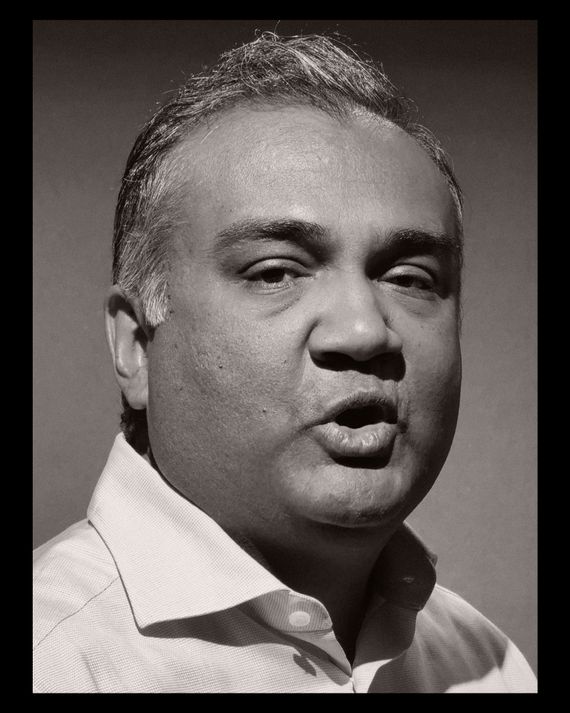

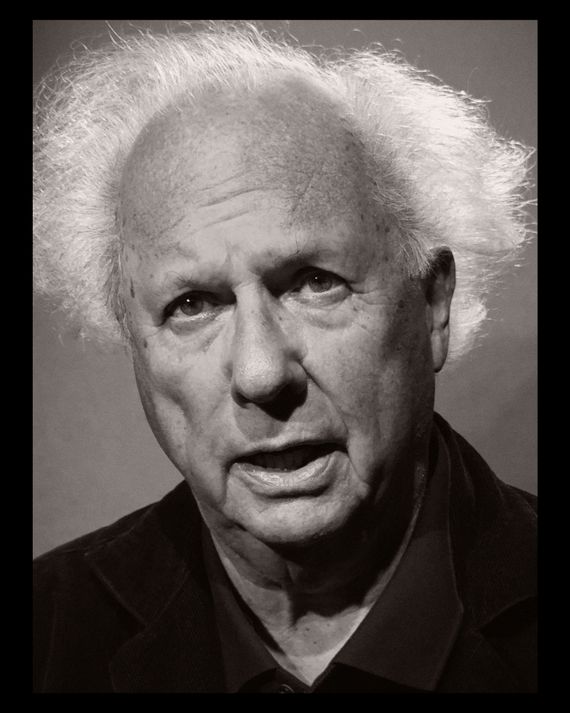

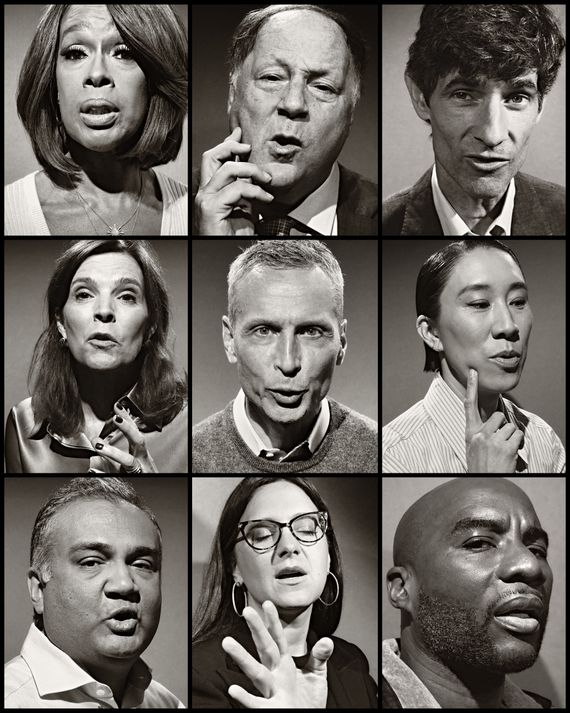

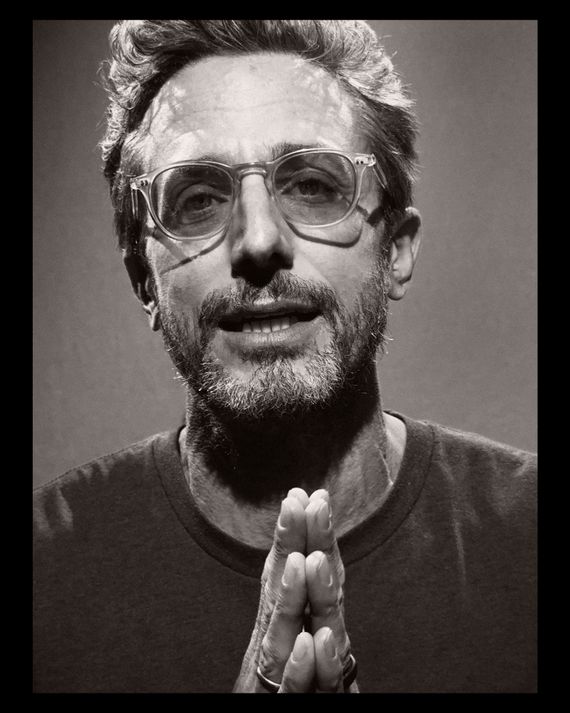

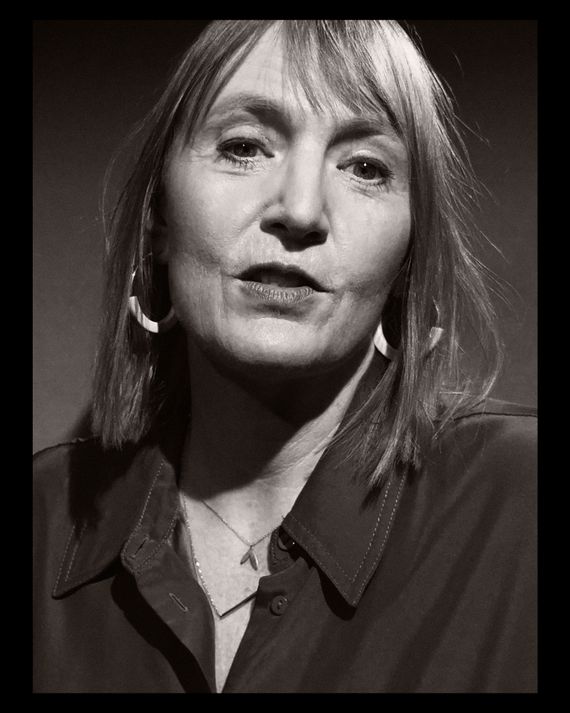

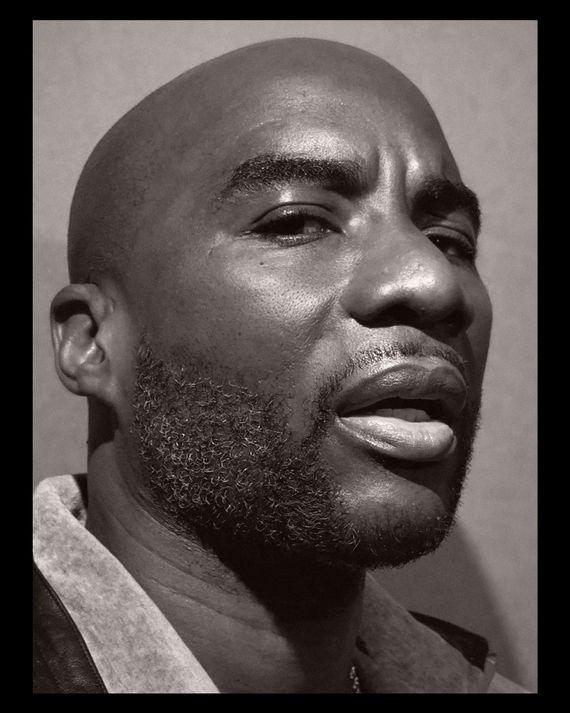

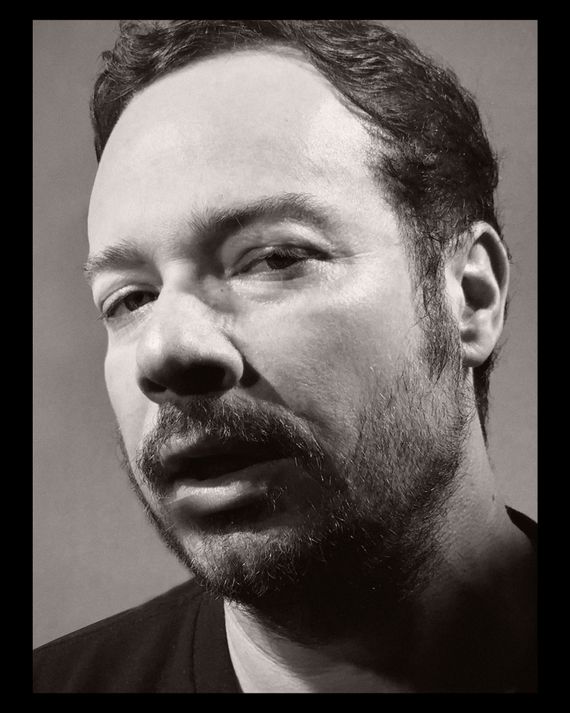

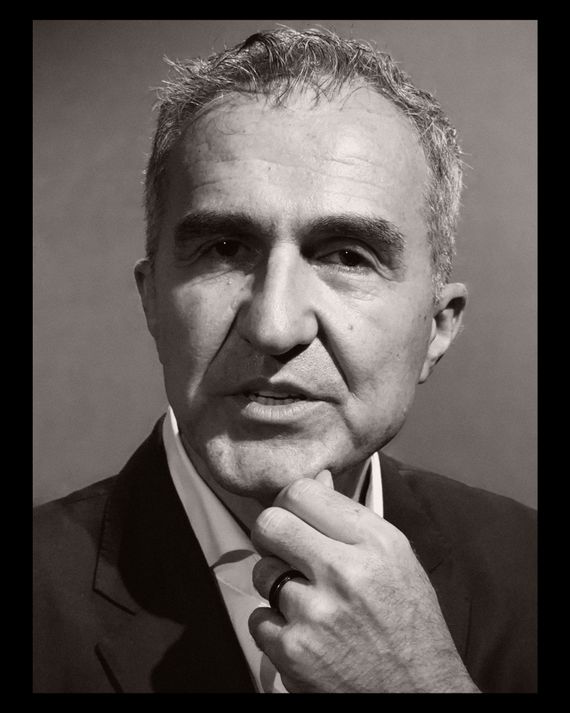

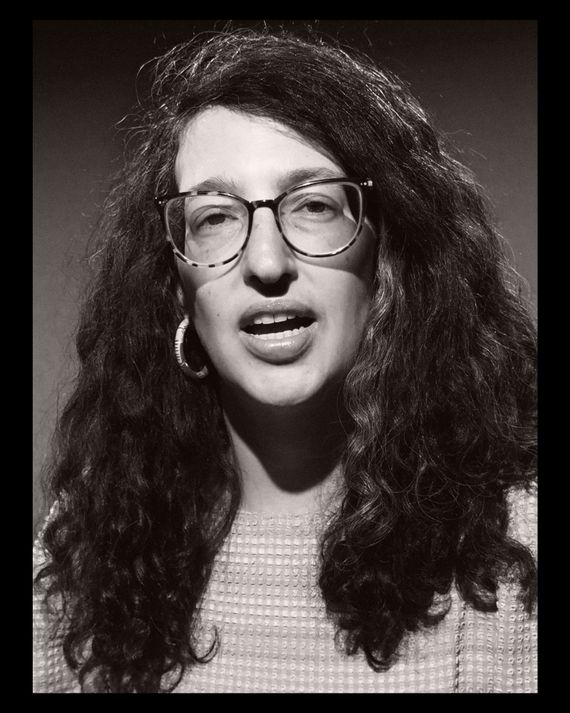

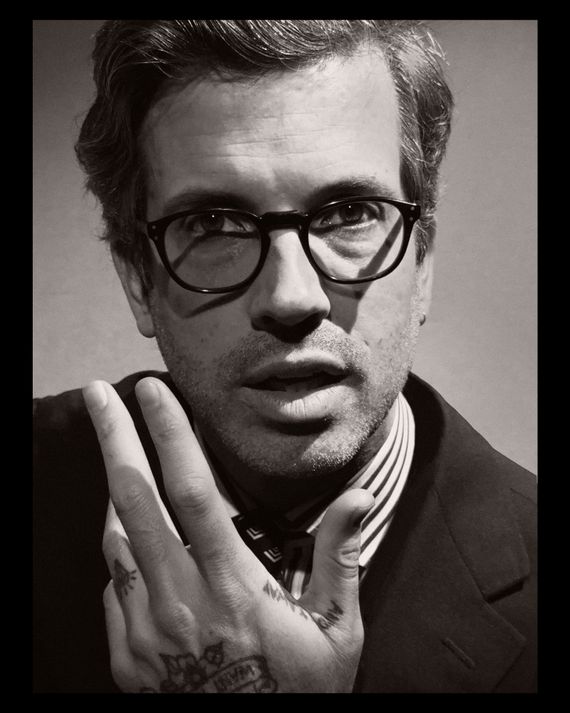

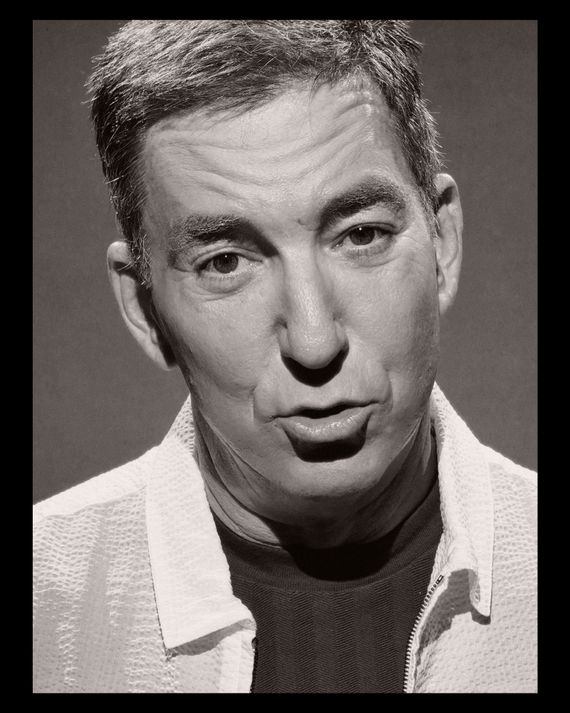

照片:保罗·库伊克为《纽约杂志》拍摄

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

本文刊登在《一个伟大的故事》中,这是纽约的阅读推荐通讯。请在此注册以便每晚接收。

On and off the record with:

记录内外的对话:

记录内外的对话:

Imran Amed, founder and editor-in-chief, The Business of Fashion. | Willa Bennett, editor-in-chief, Cosmopolitan and Seventeen. | Jeremy Boreing, co-founder and co-CEO, The Daily Wire. | Graydon Carter, founder and co-editor, Air Mail. | Sewell Chan, executive editor, Columbia Journalism Review. | Leroy Chapman Jr., editor-in-chief, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. | Charlamagne tha God, co-host, The Breakfast Club; founder, the Black Effect Podcast Network. | Eva Chen, vice-president of fashion, Meta. | Joanna Coles, chief creative and content officer, The Daily Beast. | Kaitlan Collins, anchor, CNN’s The Source. | Sam Dolnick, deputy managing editor, the New York Times. | Mathias Döpfner, CEO, Axel Springer SE. | Stephen Engelberg, editor-in-chief, ProPublica. | Bryan Goldberg, CEO, Bustle Digital Group. | Emily Greenhouse, editor, The New York Review of Books. | Glenn Greenwald, host, System Update; co-founder, The Intercept. | John Harris, co-founder and global editor-in-chief, Politico. | Radhika Jones, editor-in-chief, Vanity Fair. | Almin Karamehmedovic, president, ABC News. | Jon Kelly, co-founder and editor-in-chief, Puck. | Lauren Kern, editor-in-chief, Apple News. | Gayle King, co-host, CBS Mornings. | Jessica Lessin, founder and editor-in-chief, The Information. | Hamish McKenzie, co-founder, Substack. | Wendy McMahon, president and CEO, CBS News and Stations and CBS Media Ventures. | Kevin Merida, former executive editor, the Los Angeles Times. | John Micklethwait, editor-in-chief, Bloomberg. | Janice Min, founder and CEO, Ankler Media. | Neal Mohan, CEO, YouTube. | Matt Murray, executive editor, the Washington Post. | Samira Nasr, editor-in-chief, Harper’s Bazaar. | Mel Ottenberg, editor-in-chief, Interview. | Bill Owens, executive producer, CBS’s 60 Minutes. | Jonah Peretti, co-founder and CEO, BuzzFeed, Inc. | Jimmy Pitaro, chairman, ESPN. | Ramesh Ponnuru, editor, National Review. | Keith Poole, editor-in-chief, the New York Post Group. | Betsy Reed, editor, The Guardian US | Alison Roman, writer and chef. | Maer Roshan, co-editor-in-chief, The Hollywood Reporter. | Carolyn Ryan, managing editor, the New York Times. | Ben Shapiro, host, The Ben Shapiro Show; co-founder, The Daily Wire. | Sam Sifton, assistant managing editor, the New York Times; founding editor, New York Times Cooking. | Bill Simmons, founder and managing director, The Ringer; head of podcast innovation and monetization, Spotify. | Ben Smith, co-founder and editor-in-chief, Semafor. | Andrew Ross Sorkin, founder and editor-at-large, the New York Times’ DealBook; co-anchor, CNBC’s Squawk Box. | Simone Swink, senior executive producer, ABC’s Good Morning America. | Jake Tapper, anchor and chief Washington correspondent, CNN. | Nicholas Thompson, CEO, The Atlantic. | Emma Tucker, editor-in-chief, The Wall Street Journal. | Jim VandeHei, co-founder and CEO, Axios; co-founder, Politico. | Bari Weiss, founder and editor, The Free Press. | Will Welch, global editorial director, GQ and Pitchfork. | Gus Wenner, CEO, Rolling Stone. | Michael Wolff, author. | Matthew Yglesias, writer, Slow Boring; co-founder, Vox.com. | Jeff Zucker, CEO, RedBird IMI.

伊姆兰·阿梅德,《时尚商业》创始人兼主编。| 威拉·贝内特,《时尚》与《十七岁》主编。| 杰里米·博林,共同创始人兼首席执行官,《每日线报》。| 格雷登·卡特,创始人兼共同主编,《航空邮件》。| 苏威尔·陈,执行主编,《哥伦比亚新闻评论》。| 莱罗伊·查普曼 Jr.,《亚特兰大宪法报》主编。| 查拉马恩·塔·戈德,《早餐俱乐部》共同主持人;《黑人效应播客网络》创始人。| 艾娃·陈,Meta 时尚副总裁。| 乔安娜·科尔斯,《每日野兽》首席创意与内容官。| 凯特兰·柯林斯,CNN《消息源》主播。| 山姆·多尔尼克,《纽约时报》副主编。| 马蒂亚斯·多普夫纳,阿克塞尔·施普林格公司首席执行官。| 斯蒂芬·恩格尔伯格,ProPublica 主编。| 布莱恩·戈德堡,Bustle Digital Group 首席执行官。| 艾米莉·格林豪斯,《纽约书评》编辑。| 格伦·格林沃尔德,《系统更新》主持人;《拦截者》共同创始人。| 约翰·哈里斯,Politico 共同创始人及全球主编。| 拉迪卡·琼斯,《名利场》主编。| 阿尔敏·卡拉梅赫梅多维奇,ABC 新闻总裁。| 乔恩·凯利,Puck 共同创始人兼主编。| 劳伦·科恩,Apple News 主编。 | 盖尔·金,CBS 早间新闻联合主持人。 | 杰西卡·莱辛,《信息》创始人兼主编。 | 哈米什·麦肯齐,Substack 联合创始人。 | 温迪·麦克马洪,CBS 新闻及电台和 CBS 媒体投资公司总裁兼首席执行官。 | 凯文·梅里达,前《洛杉矶时报》执行主编。 | 约翰·米克尔斯韦特,彭博社主编。 | 贾尼斯·敏,Ankler Media 创始人兼首席执行官。 | 尼尔·莫汉,YouTube 首席执行官。 | 马特·穆雷,《华盛顿邮报》执行主编。 | 萨米拉·纳斯尔,《哈泼斯·巴扎》主编。 | 梅尔·奥滕伯格,《采访》主编。 | 比尔·欧文斯,CBS《60 分钟》执行制片人。 | 乔纳·佩雷蒂,BuzzFeed, Inc.联合创始人兼首席执行官。 | 吉米·皮塔罗,ESPN 董事长。 | 拉梅什·波努鲁,《国家评论》编辑。 | 基思·普尔,《纽约邮报》集团主编。 | 贝茜·里德,《卫报》美国版编辑。 | 艾莉森·罗曼,作家和厨师。 | 梅尔·罗尚,《好莱坞报道者》联合主编。 | 卡罗琳·瑞安,《纽约时报》执行编辑。 | 本·夏皮罗,《本·夏皮罗秀》主持人;《每日邮报》联合创始人。 | 山姆·西夫顿,《纽约时报》助理执行编辑;《纽约时报烹饪》创始编辑。 比尔·西蒙斯,创始人兼董事总经理,《The Ringer》;播客创新与货币化负责人,Spotify。| 本·史密斯,联合创始人兼主编,Semafor。| 安德鲁·罗斯·索金,创始人兼特约编辑,《纽约时报》DealBook;CNBC《Squawk Box》联合主播。| 西蒙娜·斯温克,高级执行制片人,ABC《早安美国》。| 杰克·塔珀,主播兼首席华盛顿记者,CNN。| 尼古拉斯·汤普森,首席执行官,《大西洋》。| 艾玛·塔克,主编,《华尔街日报》。| 吉姆·范德海,联合创始人兼首席执行官,Axios;Politico 联合创始人。| 巴里·韦斯,创始人兼主编,《自由新闻》。| 威尔·韦尔奇,全球编辑总监,GQ 和 Pitchfork。| 古斯·温纳,首席执行官,《滚石》。| 迈克尔·沃尔夫,作家。| 马修·伊格莱西亚斯,作家,Slow Boring;Vox.com 联合创始人。| 杰夫·扎克,首席执行官,RedBird IMI。

When this magazine revived the annual “Power Issue” last year, we assembled a list of secretly powerful New Yorkers in an effort to explain how the city actually works. This year, we were curious to understand how the news media is surviving in a time of imploding business models and record public distrust. We gathered 57 of the most powerful people in media — and rather than simply anoint them, we put them to work. What follows is a tour through the state of journalism, assembled from dozens of hours of extremely candid conversations.

当本杂志去年复刊年度“权力特刊”时,我们汇集了一份秘密强大的纽约人名单,以解释这座城市的实际运作。今年,我们想了解在商业模式崩溃和公众信任度创纪录低迷的时期,新闻媒体是如何生存的。我们聚集了 57 位媒体界最有影响力的人物——而不是简单地任命他们,我们让他们参与工作。接下来是通过数十小时极为坦诚的对话汇编而成的新闻现状巡礼。

Some executives we spoke to are in the business of keeping legacy institutions like the New York Times or the Washington Post viable; some are trying to build new media companies like Puck, The Ankler, or The Free Press; some are sole proprietors of their own brands via newsletters or audio. We focused largely on the news media: the organizations and individuals responsible for producing and distributing information to the public, whether it concerns politics or fashion or sports. And because news organizations are obviously no longer the only places — or, in some cases, even the main places — people get their news today, we didn’t look just at traditional news outlets. We also included people like Neal Mohan, head of YouTube, the platform where zoomers are increasingly likely to get their news, and Lauren Kern, head of Apple News, essentially the world’s largest newsstand.

我们采访的一些高管致力于让《纽约时报》或《华盛顿邮报》等传统机构保持活力;一些则试图建立像 Puck、The Ankler 或 The Free Press 这样的新媒体公司;还有一些则通过新闻通讯或音频独立经营自己的品牌。我们主要关注新闻媒体:那些负责向公众生产和传播信息的组织和个人,无论是涉及政治、时尚还是体育。由于新闻机构显然不再是人们获取新闻的唯一地方——在某些情况下,甚至不是主要地方——我们不仅关注传统新闻媒体。我们还包括了像 YouTube 的负责人 Neal Mohan 这样的人,年轻人越来越可能在这个平台上获取新闻,以及 Apple News 的负责人 Lauren Kern,基本上是世界上最大的报摊。

In This Issue 本期内容

All of these media insiders have watched up close as the business that undergirds journalism changed dramatically in the past decade, and almost all of them would agree that it hasn’t, for the most part, been for the better. We wanted to understand not just what this new state of media looks like but what the future of getting reliable news out in the world might actually be. Which news organizations are struggling most to find their footing, and which seem to have figured out how to find an audience? Can any of those companies get people to pay for their journalism? What’s the point of print? Are Facebook, Google, and X the enemies of the press or still, somehow, its salvation? What happened to the industry that scaled up to manufacture clickbait? And who’s going to train the next generation of journalists? Is getting 9,000 steady paying readers better than trying to reach a mass audience? And can anyone besides TikTok and Facebook even reach a mass audience these days?

所有这些媒体内部人士都近距离观察到,支撑新闻业的商业在过去十年中发生了剧烈变化,几乎所有人都同意,这种变化大多数情况下并不是向好的方向发展。我们想要了解的不仅是这种新媒体状态的样子,还有未来如何在世界上传递可靠新闻。哪些新闻机构在寻找立足点方面最为挣扎,哪些似乎已经找到了吸引观众的方法?这些公司中有谁能够让人们为他们的新闻付费?印刷媒体的意义何在?Facebook、谷歌和 X 是新闻界的敌人,还是在某种程度上仍然是它的救赎?那个曾经扩大规模以制造点击诱饵的行业发生了什么?谁将培养下一代记者?拥有 9000 名稳定付费读者是否比试图接触大众观众更好?如今除了 TikTok 和 Facebook,还有谁能够接触到大众观众?

Some unquestionably powerful figures declined to participate, and to avoid the obvious conflicts, we didn’t include any current employees from, or any conversations about, New York or its parent company, Vox Media. We also allowed those who spoke to us to be anonymous as often as they wished since our driving interest was in having genuinely honest conversations with people important enough that they can’t always be candid when quoted by name.

一些无可争议的权威人士拒绝参与,为了避免明显的冲突,我们没有包括任何来自纽约或其母公司 Vox Media 的现任员工,也没有涉及相关对话。我们还允许与我们交谈的人在他们希望的情况下保持匿名,因为我们最关心的是与那些足够重要的人进行真正诚实的对话,他们在被点名引用时并不总能坦率。

One question that emerged was whether any organization or individual has the ability to influence culture or shape perspectives as was once common in this business; that role today seems to rest more with social platforms and search engines, as well as the singular figure of Elon Musk. Our sources struggled to identify how power in the media works now. It’s not that no one has power anymore, but their reach is increasingly narrow and threatened by the rapidly eroding agreement over the facts.

一个出现的问题是,是否有任何组织或个人能够像过去那样影响文化或塑造观点;如今,这一角色似乎更多地落在社交平台和搜索引擎上,以及埃隆·马斯克这一独特人物身上。我们的消息来源在识别媒体权力如何运作时遇到了困难。并不是说现在没有人拥有权力,而是他们的影响力越来越狭窄,并受到对事实迅速侵蚀的共识的威胁。

Still, we found a lot of optimism about the media business and its future. Even those who are gloomy about the state of the industry see a lot of good work being done in their own shops and those of their rivals. As one editor-in-chief impishly put it, “Everyone who’s not having fun and just doing 20th-century stuff is so boring. It’s too much work to not have fun in it. The media universe will keep transforming, and some changes will be for the better. Five years from now, we’ll all be different because it feels like we’re on the cusp of some crazy new thing.”

尽管如此,我们发现对媒体行业及其未来充满了乐观。即使是那些对行业现状感到沮丧的人,也看到自己和竞争对手的工作中有很多优秀的成果。正如一位主编顽皮地说:“那些不享受乐趣、只做 20 世纪工作的家伙真无聊。没乐趣的工作太累了。媒体宇宙将不断转型,有些变化将是积极的。五年后,我们都会有所不同,因为我们感觉正处于某种疯狂新事物的边缘。”

Contents: 内容:

The Advertising Business | AI | Air Mail | Apple News | Axios | Jeff Bezos | The Bosses | A Brief History | CNN.com | Condé Nast | Covers | Entry-Level Journalists | Facebook | Google | Local News | The Los Angeles Times | Media Gossip | Media Moguls | Rupert Murdoch | Elon Musk | Newsletters | The New York Times | Print | Puck | Punchbowl News | The Scoop Business | Semafor | Subscriptions | Substack | TV News | The Wall Street Journal | The Washington Post | Who Controls the Media? | YouTube

广告业务 | 人工智能 | 空邮 | 苹果新闻 | Axios | 杰夫·贝索斯 | 领导者 | 简史 | CNN.com | 康泰纳仕 | 封面 | 入门级记者 | Facebook | Google | 本地新闻 | 洛杉矶时报 | 媒体八卦 | 媒体大亨 | 鲁珀特·默多克 | 埃隆·马斯克 | 新闻通讯 | 纽约时报 | 印刷 | Puck | Punchbowl 新闻 | 独家商业 | Semafor | 订阅 | Substack | 电视新闻 | 华尔街日报 | 华盛顿邮报 | 谁控制媒体? | YouTube

‘The News Media Business Is …’

“新闻媒体行业是……”

“Collapsing as always, I’m reliably told.” — Ben Smith • “Going to hell in a handbasket. There may be, down the road, a way out of it, but I just don’t know what it is.” — Graydon Carter • “Like the fire swamp in The Princess Bride. It is treacherous in places, you could go up in flames, you could be attacked by a rodent of unusual size, but you can be a little bit of a pirate and anticipate those threats and figure out how to defuse them.” — Radhika Jones • “It’s in flux, and the small and strong will survive.” — Janice Min • “I don’t feel like employees understand how precarious it is at all.” — Carolyn Ryan • “Going to look very different over the next five years than it did for the previous 50.” — Jeff Zucker • “I think you’d have to be crazy to begin a career in journalism right now.” — A media executive who knew better than to say it on the record

“总是崩溃,我可靠地被告知。” — 本·史密斯 • “一切都在走向地狱。未来可能会有出路,但我不知道是什么。” — 格雷登·卡特 • “就像《公主新娘》中的火沼泽。某些地方非常危险,你可能会被火焰吞噬,可能会被一种不寻常大小的啮齿动物攻击,但你可以稍微像个海盗,预见这些威胁并想办法化解它们。” — 拉迪卡·琼斯 • “一切都在变化,强者和小者将会生存。” — 贾尼斯·敏 • “我觉得员工根本不明白形势有多么不稳定。” — 卡罗琳·瑞安 • “未来五年将与过去五十年大相径庭。” — 杰夫·扎克 • “我认为现在开始新闻事业的人得是疯了。” — 一位知道不该公开说这话的媒体高管

First, a Brief History of How We Got Here.

首先,我们如何走到这里的简要历史。

According to five media executives.

根据五位媒体高管的说法。

The Trouble Started When the Internet Crushed the Old Advertising Business …

麻烦始于互联网冲击了传统广告行业……

“We lost our business model because of the internet, which everybody knows, but not for the reasons they think. It was simply that the tech companies built a better advertising model and we weren’t able to respond quickly enough. The newspapers lost their classified ads, the local newspapers lost their monopoly on distribution for certain regions, and the magazines lost their monopoly on distribution among different interest groups. If you wanted to, 20 years ago, sell golf balls, you bought an ad in Golf magazine; now, you buy a Facebook ad targeted to people who have re-upped their golf-club memberships. So there just was a better way of advertising. And we did not see that at the beginning of this tech revolution. We were so excited about infinite free distribution we didn’t see that the whole premise of the business model that supported this thing was getting undercut relatively quickly. We didn’t respond appropriately and didn’t build the right business models quickly enough. Then by the time we did, most of us had our lunch eaten. What is one main way The Atlantic and other serious publications drive subscriptions? They buy ads on Facebook.” — Nicholas Thompson, CEO, The Atlantic

“我们失去了商业模式,这大家都知道,但原因并不是他们想的那样。实际上是科技公司建立了更好的广告模式,而我们未能迅速做出反应。报纸失去了分类广告,当地报纸失去了在特定地区的分发垄断,杂志失去了在不同兴趣群体中的分发垄断。如果你想在 20 年前卖高尔夫球,你会在《高尔夫》杂志上买广告;而现在,你会在 Facebook 上购买针对续费高尔夫俱乐部会员的广告。因此,广告的方式变得更好。而在这场科技革命的初期,我们并没有意识到这一点。我们对无限免费的分发感到兴奋,以至于没有看到支撑这一切的商业模式的整个前提正在相对快速地被削弱。我们没有做出适当的反应,也没有迅速建立正确的商业模式。等我们开始行动时,大多数人的午餐已经被别人吃掉了。《大西洋月刊》和其他严肃出版物推动订阅的主要方式是什么?他们在 Facebook 上购买广告。”“—— 尼古拉斯·汤普森,《大西洋月刊》首席执行官”

Then, Some Digital Brands Chased New Ads by Building Enormous Audiences …

然后,一些数字品牌通过建立庞大的受众群体追逐新的广告……

“One brand-new thing in the teens was this fantasy that you could become tech-rich off journalism. Certain places began playing a scale game, thinking they could get a toehold against Google and Facebook. Of course, to grow as fast as they thought they would need to, they decided they had to take venture money — that felt like, We want to be a tech company, and we’re going to do what tech people do. It had shades of WeWork, trying to tell a story about yourself that investors could get behind while raising money, when really you’re doing what everyone else is, which is pretty straightforward: making content and trying to sell sponsorship against it. Then everyone got underwater. I liken it to everyone who got an easy mortgage on a home in 2007 not knowing they were already in default.” — Janice Min, founder and CEO, Ankler Media

“十几岁时一个全新的想法是,您可以通过新闻业变得富有。某些地方开始玩规模游戏,认为他们可以在谷歌和脸书面前占据一席之地。当然,为了像他们想象的那样快速增长,他们决定必须接受风险投资——这感觉就像,我们想成为一家科技公司,我们要做科技公司所做的事情。这有点像 WeWork,试图讲述一个投资者可以支持的故事,同时筹集资金,而实际上你所做的和其他人一样,都是相当简单的:制作内容并试图为其销售赞助。然后每个人都陷入困境。我把它比作 2007 年那些轻松获得房屋抵押贷款的人,他们并不知道自己已经违约。” — 贾尼斯·敏,Ankler Media 创始人兼首席执行官

Which Has Put Them Completely at the Mercy of Facebook and Google.

这使他们完全处于 Facebook 和 Google 的掌控之中。

“Nobody wants to be in a position where their company is overwhelmingly reliant on any trillion-dollar entity for distribution or monetization, right? That’s just a very vulnerable position to put your business in. There are plenty of recent examples of companies that learned the hard way.” — Jon Kelly, editor-in-chief, Puck

“没有人希望自己的公司在分销或货币化方面过于依赖任何一家万亿级企业,对吧?这无疑是让你的业务处于一个非常脆弱的境地。最近有很多公司通过艰难的方式学到了这一点。” — 乔恩·凯利,Puck 主编

“I was very hopeful that the big tech platforms would see us as very complementary. There was an amazing ten-year run of a symbiotic relationship and then the social platforms got powerful and strangled a lot of the companies that were the most focused on making content for them. It was painful for us. We are finally on the other side of this shift and building our business on direct traffic. But it was a death sentence for some of the publishers that were really focused on getting their audience from Facebook.” — Jonah Peretti, CEO, BuzzFeed

“我曾非常希望大型科技平台能将我们视为非常互补的伙伴。我们经历了十年的共生关系,期间非常美好,但社交平台变得强大,扼杀了许多专注于为他们制作内容的公司。这对我们来说是痛苦的。我们终于走出了这一转变,正在基于直接流量建立我们的业务。但这对一些非常依赖 Facebook 获取受众的出版商来说,简直是死刑。” — 乔纳·佩雷蒂,BuzzFeed 首席执行官

“Google really undermined professional journalism when they moved away from PageRank. It’s one thing to place less emphasis or weight on authority. It’s another to actively harm those publishing houses that have reputations and authority. And I think that they spent the past ten years seeing how far they can push their monopoly and what they can get away with. What they found is they can get away with a great deal.” — Bryan Goldberg, CEO, Bustle Digital Group

“谷歌在放弃 PageRank 时确实削弱了专业新闻业。减少对权威的重视是一回事,主动伤害那些拥有声誉和权威的出版机构则是另一回事。我认为,他们在过去十年里一直在观察他们的垄断能推得多远,以及他们能逃避多少责任。他们发现,他们可以逃避很多。” — 布斯特数字集团首席执行官布莱恩·戈德堡

The Media’s Most Promising New Business Idea? Make Something Worth For.

媒体最有前景的新商业想法?创造值得付费的内容。

It’s pretty simple, explains Bloomberg editor-in-chief John Micklethwait: “You produce good content; you get people to pay for it; the money you get from those people paying for it, you produce more good content. If you don’t have a system whereby you have consumers paying for your content, then you are generally in a perilous state.” It helps that many people use Bloomberg’s content to direct their investment decisions, so they will definitely pay for it. But his larger point stands for everyone building a paywall. “The business no longer is ‘You want to sell a couch? We’ll charge you a lot of money to reach every one of our readers,’” says ProPublica’s Stephen Engelberg. “It’s now ‘Do you want to have the journalism that keeps democracy alive? Would you be willing to pay $10 a month?’” Not every outlet charges, of course. But if you can persuade readers to subscribe, you’ve created a more direct model for making money off them. “Subscription revenue is the important business metric,” says an editor-in-chief. What’s unknown is how many subscriptions readers will pay for. “A sustainable business model for journalism is going to need people willing to pay for five or seven or ten new subscriptions instead of one or two,” explains Columbia Journalism Review’s Sewell Chan. “The Times or The Wall Street Journal presumably, or maybe CNN if they’re wildly successful, is spot No. 1. And everybody else, from Vanity Fair to the Miami Herald, is competing for spot No. 2. That’s not sustainable for our industry.”

这很简单,彭博社总编辑约翰·米克尔斯韦特解释道:“你制作优质内容;让人们为此付费;你从这些付费的人那里获得的钱,用来制作更多优质内容。如果你没有一个让消费者为你的内容付费的系统,那么你通常处于危险状态。”许多人使用彭博社的内容来指导他们的投资决策,因此他们肯定会为此付费。但他更大的观点适用于所有建立付费墙的人。“商业不再是‘你想卖沙发吗?我们会收你很多钱,让你接触到我们每一位读者,’”普罗公共事务的斯蒂芬·恩格尔伯格说。“现在是‘你想要维持民主的新闻吗?你愿意每月支付 10 美元吗?’”当然,并不是每个媒体都收费。但如果你能说服读者订阅,你就创造了一种更直接的盈利模式。“订阅收入是重要的商业指标,”一位总编辑说。未知的是,读者愿意为多少个订阅付费。 “一个可持续的新闻商业模式需要人们愿意为五个、七个或十个新订阅付费,而不是一个或两个,”哥伦比亚新闻评论的苏威尔·陈解释道。“《纽约时报》或《华尔街日报》,或者如果 CNN 非常成功的话,可能是第一名。而其他所有媒体,从《名利场》到《迈阿密先驱报》,都在争夺第二名。这对我们的行业来说是不可持续的。””

In the Subs Business, Niche Is the New Scale.

在子业务中,细分市场是新的规模。

To many, the most instructive failure of 2024 was The Messenger, an all-things-to-all-people news site run by ex Condé Nast and People executives with a “chief growth officer” formerly of Gawker Media. It planned on building out a 550-person newsroom and flooding the internet with viral scoops but instead burned through most of its $50 million in funding within a year and shut down. “I’m always suspicious when someone has a huge splashy launch saying they’re going to get up to 300 million page views in six months and reach a massive national audience,” says Betsy Reed, editor of The Guardian US. “I just feel like you can’t do that out of the gate. You need to have a much clearer grasp of who you’re reaching and why you’re going to be relevant.” What actually has succeeded this year are operations — many of them run through Substack — that have low overhead and a focused appeal. Some longtime media executives find this new world befuddling. “I’m surprised that people are okay with the subscription model, where they don’t have that many listeners or viewers but are making money, so they’re just good with it,” says one of them. “The Substack writers, people with Patreon podcasts. My generation was wired completely differently. We wanted to be read or listened to by as many people as possible. And now this new generation is like, I’m totally cool with having 9,000 die-hard fans.”

对许多人来说,2024 年最具启发性的失败是《信使》,这是一个由前康泰纳仕和《人物》高管运营的全方位新闻网站,首席增长官曾在 Gawker Media 工作。该网站计划建立一个 550 人的新闻编辑部,并在互联网上发布病毒式新闻,但在一年内就耗尽了 5000 万美元的资金并关闭了。“当有人大肆宣传他们将在六个月内获得 3 亿次页面浏览量并吸引大量全国观众时,我总是感到怀疑,”《卫报》美国版的编辑贝茜·里德说。“我觉得你不能一开始就做到这一点。你需要更清楚地了解你要接触的人是谁,以及你为什么会相关。”实际上,今年成功的是一些运营——许多通过 Substack 进行——它们的开销低且吸引力集中。一些长期的媒体高管发现这个新世界令人困惑。“我很惊讶人们对订阅模式感到满意,尽管他们没有那么多听众或观众,但仍然在赚钱,所以他们对此感到满意,”其中一位表示。“Substack 的作家,拥有 Patreon 播客的人。” 我的一代人完全不同。我们希望被尽可能多的人阅读或倾听。而现在这一代人则觉得,拥有 9000 个死忠粉丝完全没问题。”

Up for Punchbowl.

为 Punchbowl 出资。

The Congress-focused media company Punchbowl News, which was founded by Politico veterans Jake Sherman and Anna Palmer in 2021, is well read inside the Beltway. “It’s so small and it’s so particular, and yet it seems like it has impact,” says Carolyn Ryan of the Times. “I don’t even know how many reporters they have — it feels like just a handful — but they really seem to have a sense of mission and what value they bring.” That value is priced at $350 a year — a lot for a general reader, but, as with Politico Pro, such subscriptions are often treated as a business expense by anyone with a need to be in the know. “Instead of them being like, Okay, this newsletter is designed so that 10 million people will open it and read it,” says The Daily Wire’s Ben Shapiro, “they’ve designed a letter that’s meant for 10,000 people to open and read it but to pay a higher rate in order to do that.” (There have been reports that the Washington Post is looking at buying it, which the Post denies.)

专注于国会的媒体公司 Punchbowl News 由 Politico 的资深人士 Jake Sherman 和 Anna Palmer 于 2021 年创立,在华盛顿特区内广受欢迎。“它如此小巧而独特,但似乎却有影响力,”《纽约时报》的 Carolyn Ryan 说。“我甚至不知道他们有多少记者——感觉只有一小部分——但他们似乎真的有一种使命感和他们所带来的价值。”这个价值的年费为 350 美元——对于普通读者来说,这个价格不算便宜,但对于任何需要了解信息的人来说,这种订阅通常被视为商业开支。“与其说他们设计这个通讯是为了让 1000 万人打开并阅读,不如说,”《每日线》的 Ben Shapiro 说,“他们设计了一封信,旨在让 1 万人打开并阅读,但为了做到这一点,付出更高的费用。”(有报道称《华盛顿邮报》正在考虑收购该公司,但《邮报》对此予以否认。)

For $12.99 a Month, Apple News Subsidizes Seriousness …

每月 12.99 美元,苹果新闻补贴严肃性……

Apple News has essentially created an iPhone-based newsstand with actual human editors culling news from a variety of sources for its users, some of whom pay for access to journalism that publishers offer only to subscribers. “It’s going back to a very old-fashioned skill of human curation of what you’re going to highlight,” says The Ankler’s Janice Min. “It’s a little bit like the legacy-media jamboree.”

苹果新闻基本上创建了一个基于 iPhone 的新闻摊位,实际的人类编辑从各种来源为用户筛选新闻,其中一些用户为仅向订阅者提供的新闻内容付费。“这回归了一种非常传统的人类策展技能,决定你要突出什么,”《Ankler》的贾尼斯·敏说。“这有点像传统媒体的盛会。”

The editorial program is run by Lauren Kern, a former editor at New York and The New York Times Magazine. Her team spotlights features as well as breaking news stories, “narrowing down the best possible source of information at that particular time” in order to figure out, as Kern puts it, “how we reach the broadest possible audience with the best possible information.”

该编辑项目由劳伦·科恩(Lauren Kern)负责,她曾是《纽约杂志》和《纽约时报杂志》的编辑。她的团队不仅关注特写报道,还关注突发新闻,“在特定时间内缩小最佳信息来源”,以便如科恩所说,“我们如何以最佳信息覆盖尽可能广泛的受众。”

“Apple News provides a huge lift to our stories,” says Betsy Reed. “We reach this vast audience that otherwise we wouldn’t achieve on our own.” “If you’re a small publisher,” says Sewell Chan, “Apple News is like a godsend. It’s free traffic.”

“苹果新闻为我们的故事提供了巨大的支持,”贝茜·里德说。“我们能够接触到这个庞大的受众,否则我们无法单独实现。” “如果你是一个小型出版商,”苏威尔·陈说,“苹果新闻就像是上天的恩赐。这是免费的流量。”

Publishers behind the Apple News+ paywall also get paid in a system a bit like Spotify’s. All those monthly fees get pooled, and a portion is allocated to publishers based on how many minutes people spend on their stories. (The monthly rate works out to a few cents for every “engaged minute” an article attracts.) This Apple money has recently grown to be a significant contribution to many outlets’ overall business — and one that, they calculate, more than makes up for any direct-subscription revenue it cannibalizes.

苹果新闻+付费墙背后的出版商也以一种类似于 Spotify 的方式获得报酬。所有的月费被汇集在一起,部分资金根据人们在他们的故事上花费的分钟数分配给出版商。(每篇文章吸引的“参与分钟”大约能换来几分钱的月费。)这笔苹果资金最近已成为许多媒体整体业务的重要贡献——他们计算认为,这笔收入足以弥补其所侵蚀的任何直接订阅收入。

If It Doesn’t Turn on Publishers. Like Every Other Tech Giant Has So Far.

如果它不启动出版商。就像其他科技巨头迄今为止所做的那样。

What’s to stop Apple News from turning off the spigot? Not much. “I think there’s a lot of media businesses that are relying on Apple News right now and probably in too much of a way,” says Rolling Stone’s Gus Wenner. Like other relationships with tech companies that go awry, “it’s a double-edged sword: It can be good, but it’s out of your hands and it can get pulled away.”

有什么能阻止苹果新闻关闭供给吗?没什么。“我认为现在有很多媒体企业过于依赖苹果新闻,”《滚石》杂志的古斯·温纳说。就像与其他科技公司关系不顺时一样,“这是一把双刃剑:它可能是好的,但它不在你的掌控之中,随时可能被抽走。”

Who’s Gonna Pay for CNN.com?

谁来为 CNN.com 买单?

With cable fees under pressure from cord-cutting, CNN CEO Mark Thompson, who previously was responsible for building the paywall around the New York Times, has introduced a subscription plan starting at $3.99 a month. If even a fraction of CNN.com’s 150 million unique monthly viewers choose to pay, the plan would provide a windfall. Will what worked for a newspaper work for cable news?

随着因用户取消有线电视而导致的有线费用压力加大,CNN 首席执行官马克·汤普森(Mark Thompson)推出了一项订阅计划,起价为每月 3.99 美元。 如果 CNN.com 每月 1.5 亿的独立访客中即使只有一小部分选择付费,这项计划将带来丰厚的收益。 对于报纸有效的做法是否也能适用于有线新闻?

“If he can find a way to package video for consumer subscribers, then that’s interesting. The evidence so far is that it’s gone the other way around: The people who’ve got successful subscription models tend to be print people who’ve added video as part of that,” says an editor. “So there is a suspicion that to make a consumer-news thing work, you need to have a version of what we used to call ‘print’ in it.”

“如果他能找到一种方式将视频打包给消费者订阅者,那就很有意思。目前的证据表明,情况正好相反:那些成功的订阅模式往往是那些将视频作为一部分的印刷媒体,”一位编辑说。“因此,有一种怀疑,认为要让消费者新闻的东西运作起来,你需要有我们曾经称之为‘印刷’的版本。”

“All eyes are on Mark Thompson and what happens at CNN, in part because of how he overhauled the Times, and he seems like somebody who might try something a little bit more daring. He’s also got more at stake,” says a TV executive who notes that while CNN’s ratings and advertising are having problems, “it also has tremendous global resources, and how could it find different ways to deliver what people want? I mean, that’d be pretty exciting to watch and see.”

“所有的目光都集中在马克·汤普森和 CNN 的未来上,部分原因是他如何彻底改革了《纽约时报》,而且他似乎是一个可能会尝试一些更大胆做法的人。他的利益也更多,”一位电视高管表示,尽管 CNN 的收视率和广告面临问题,“但它也拥有巨大的全球资源,它如何找到不同的方式来满足人们的需求呢?我的意思是,这将是非常令人兴奋的观看和观察。”

But not everyone is expecting much. “They haven’t figured out just fundamentally what they’re for, what their use is,” says one pessimistic editor-in-chief. And their past experiments have failed spectacularly. Remember CNN+?

但并不是每个人都抱有太大期望。“他们根本还没有弄清楚他们的目的是什么,他们的用途是什么,”一位悲观的主编说道。而他们过去的实验也以惊人的方式失败了。还记得 CNN+吗?

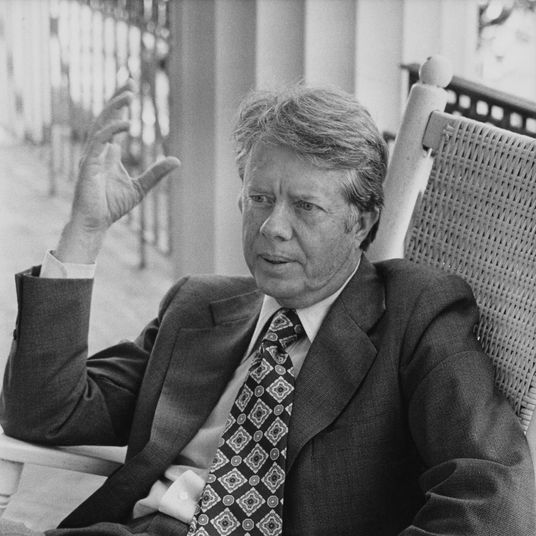

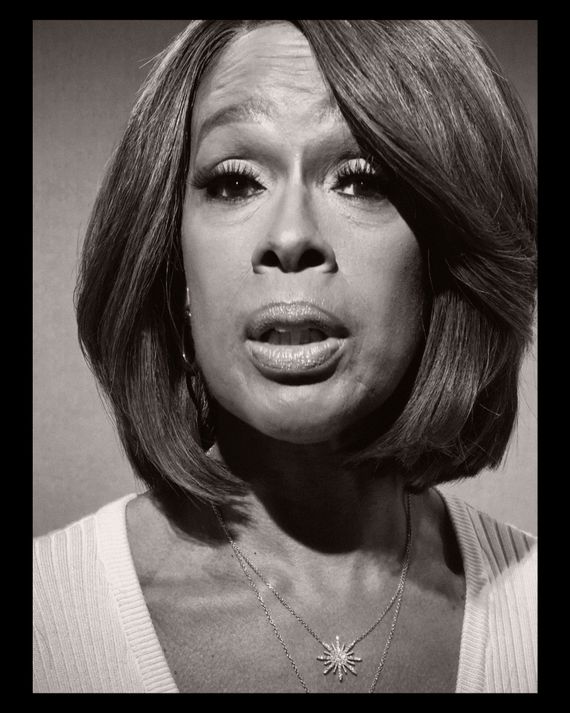

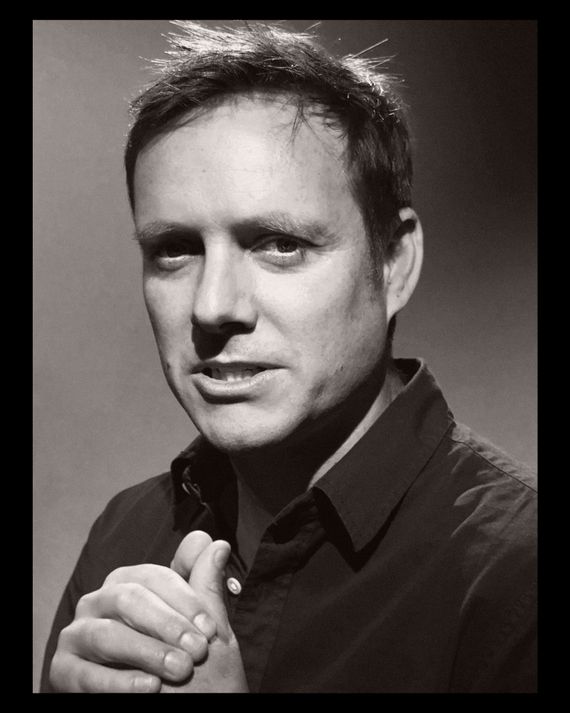

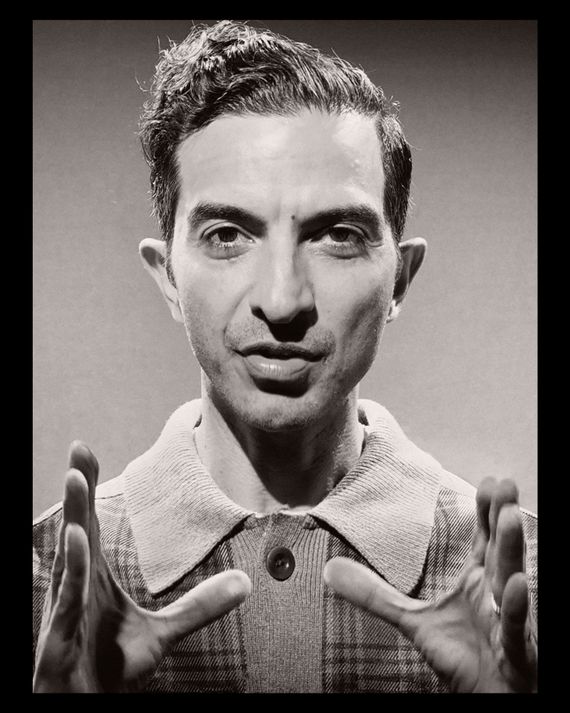

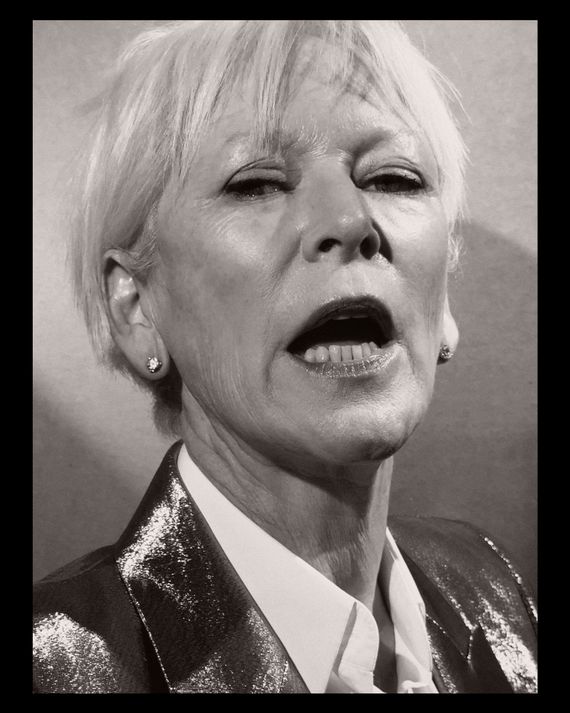

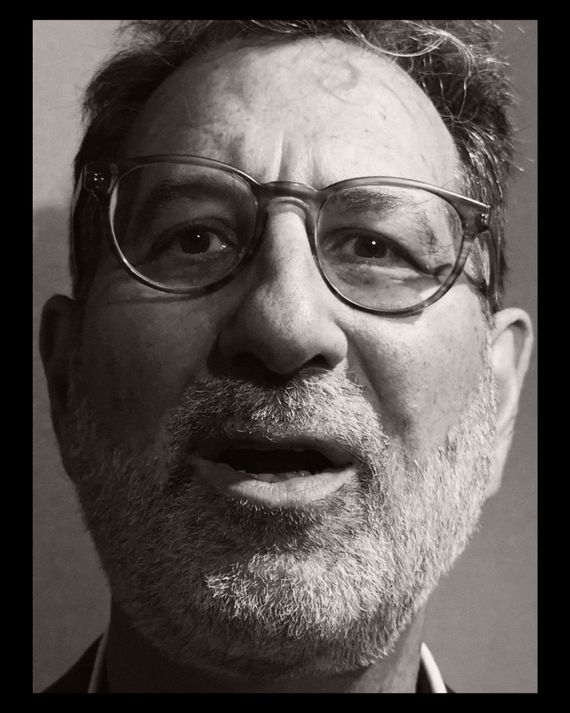

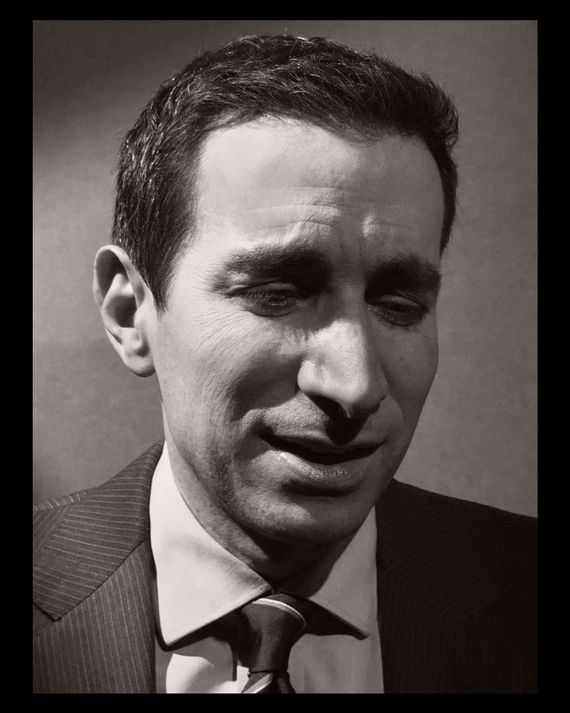

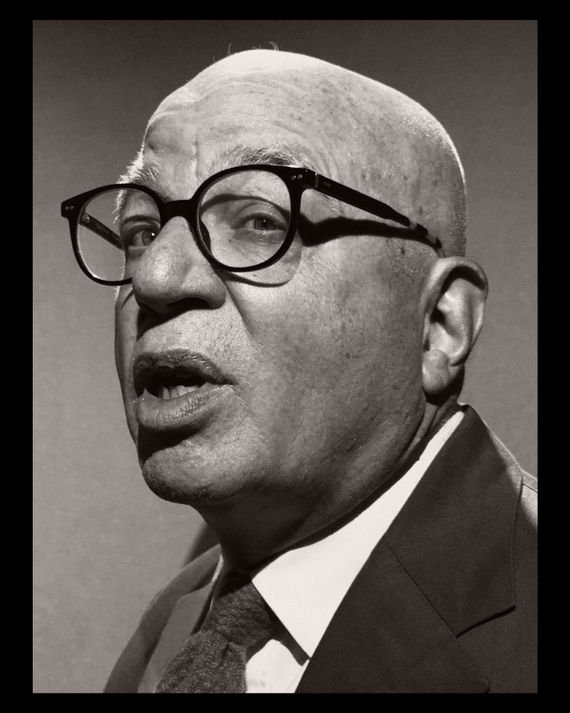

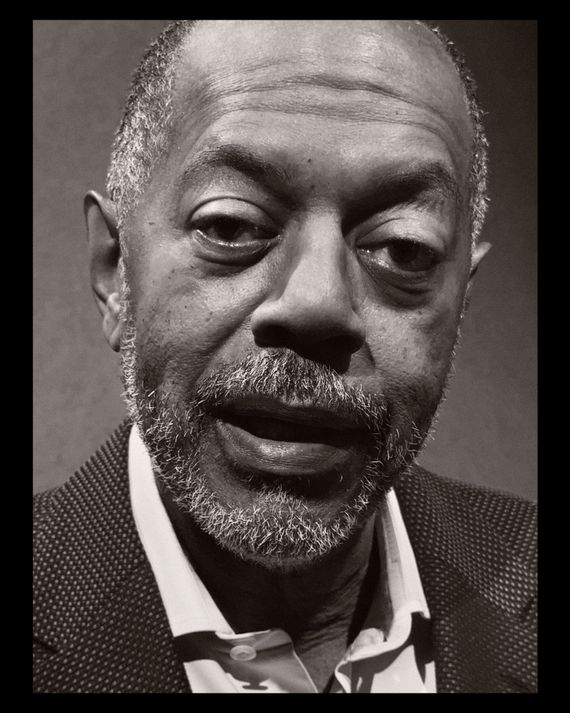

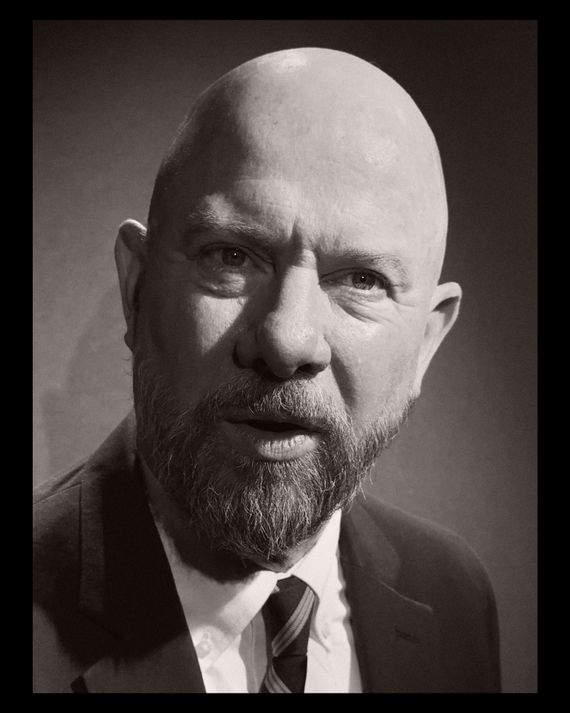

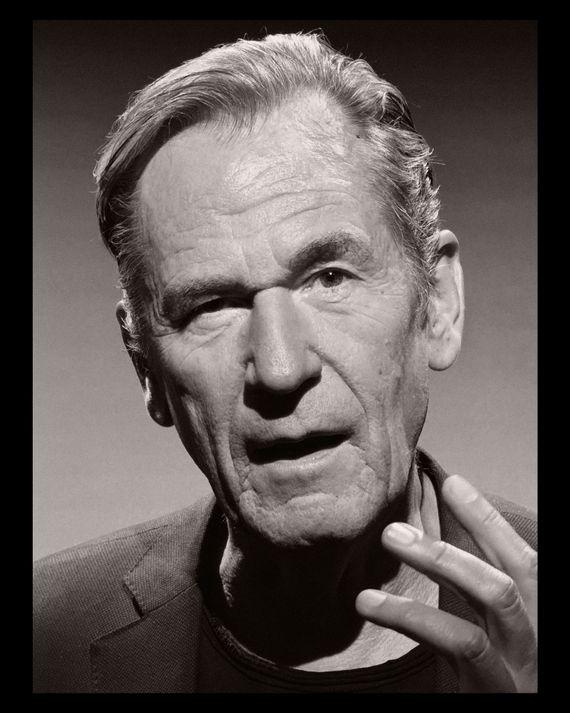

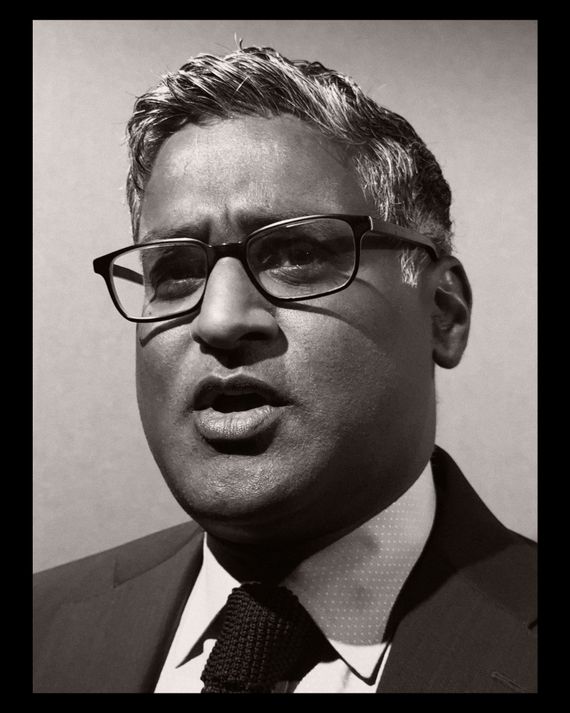

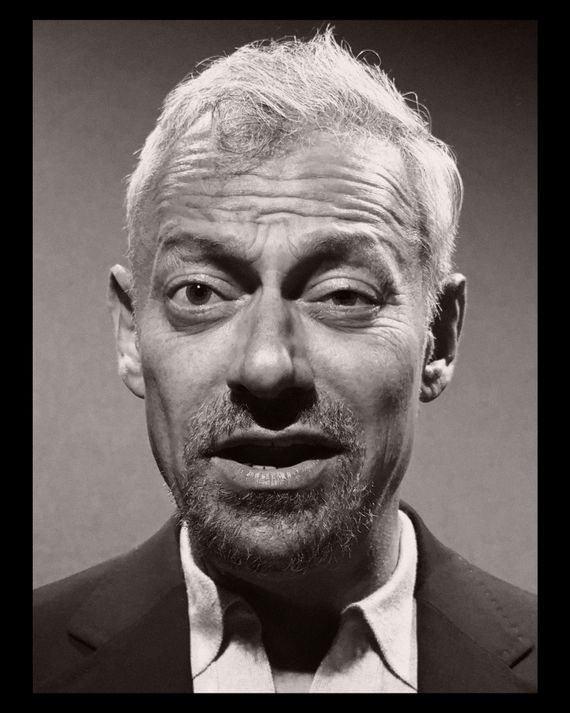

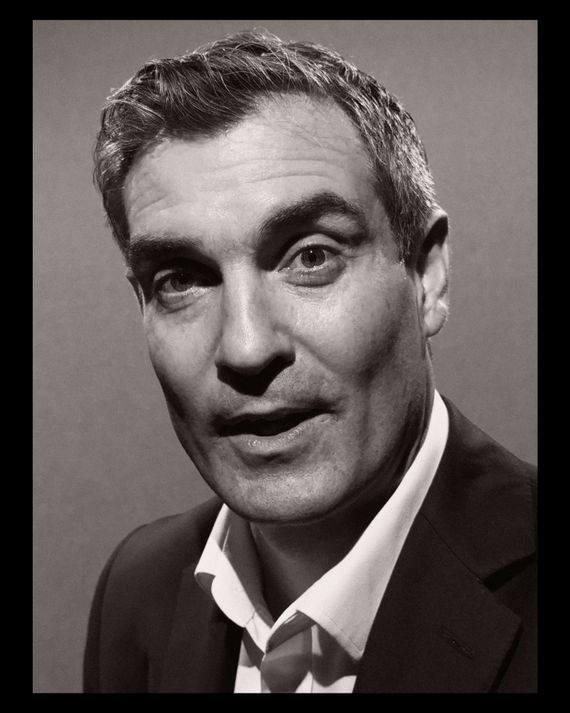

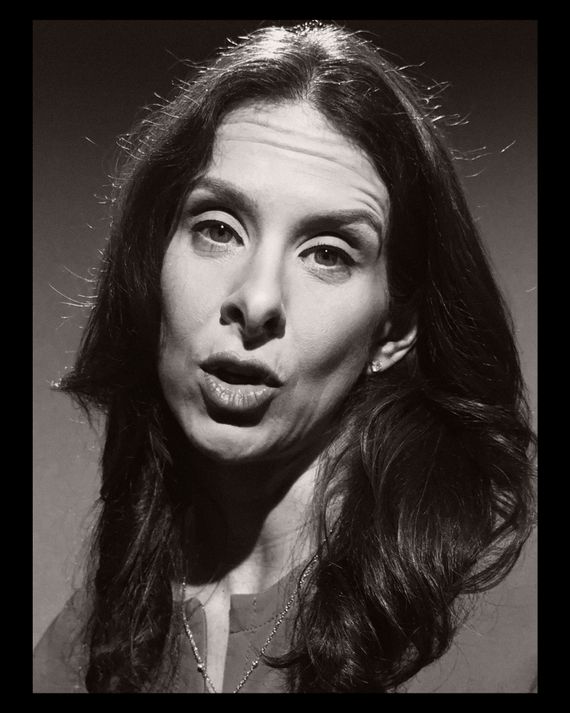

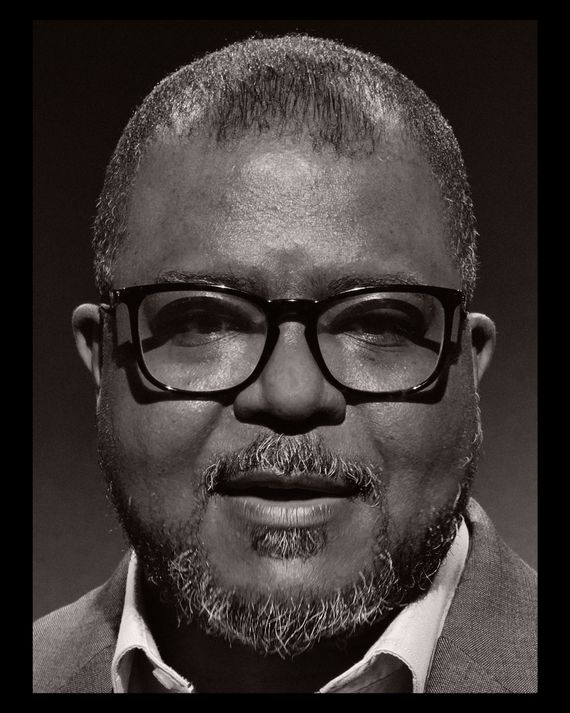

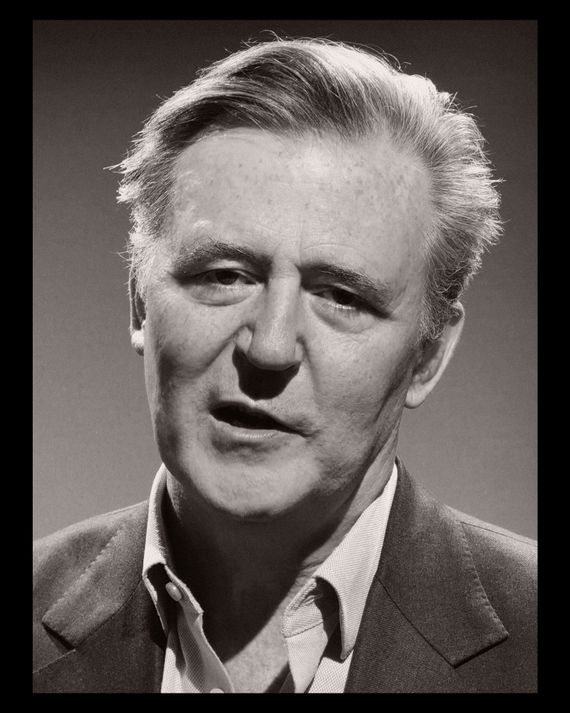

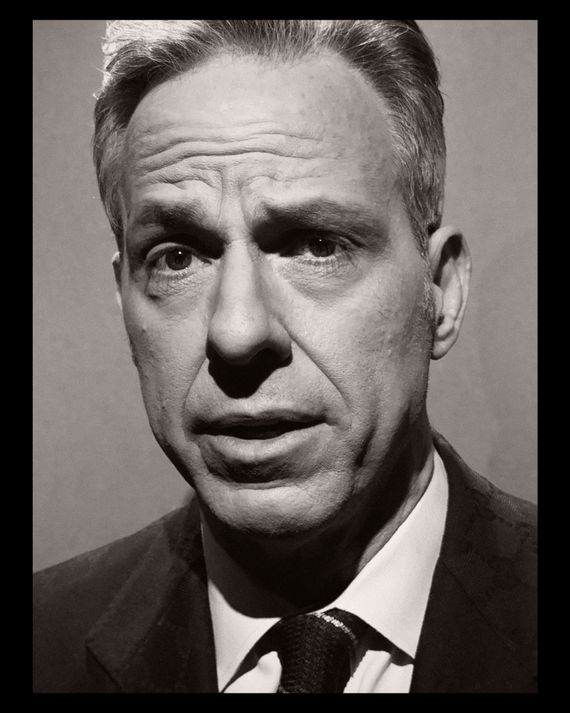

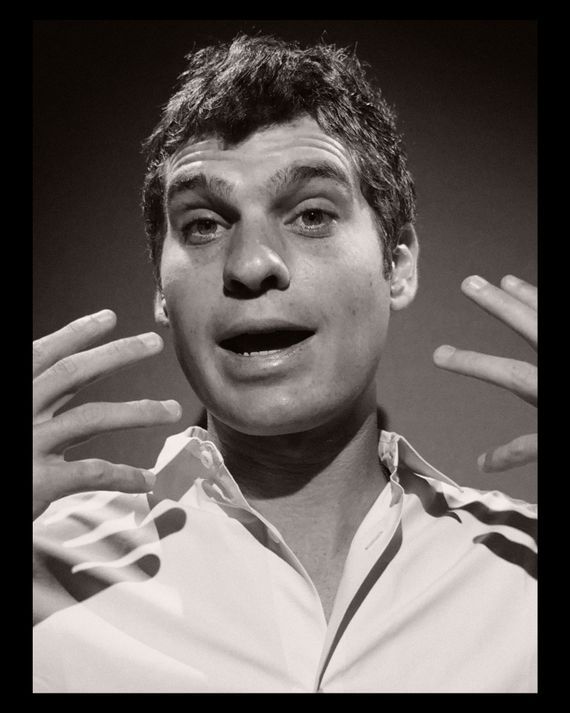

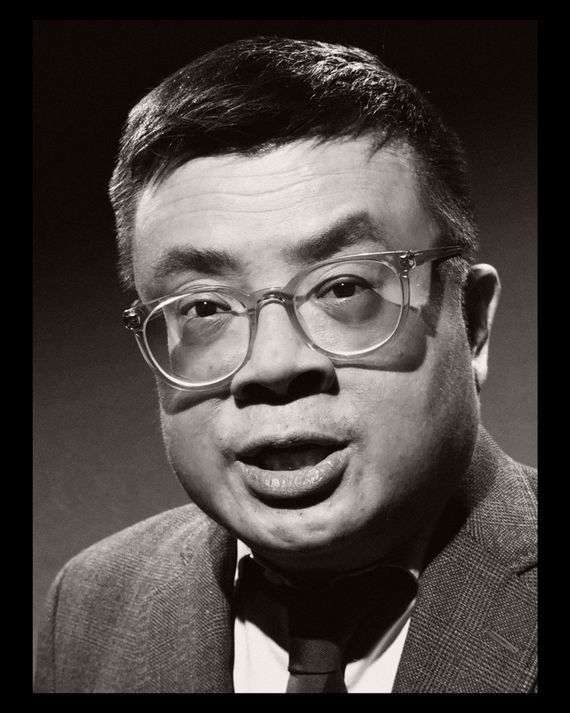

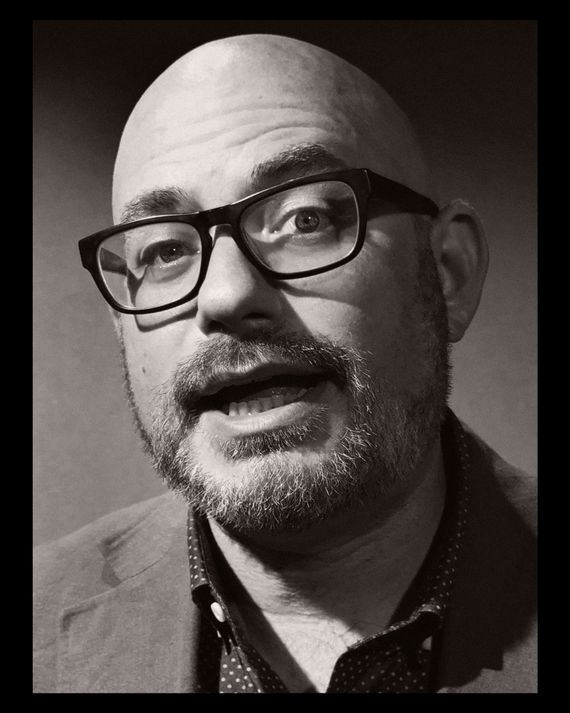

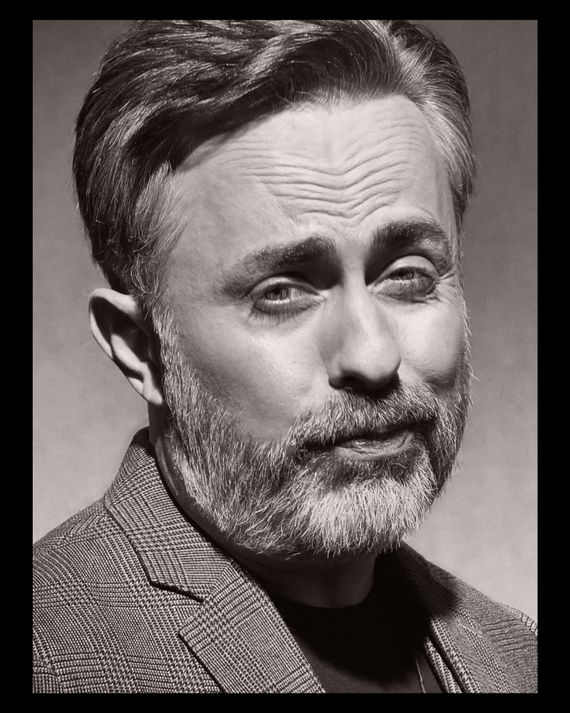

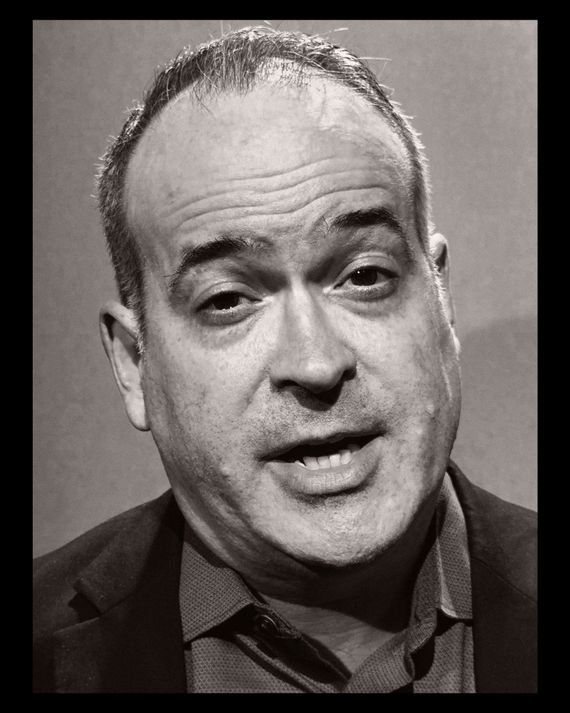

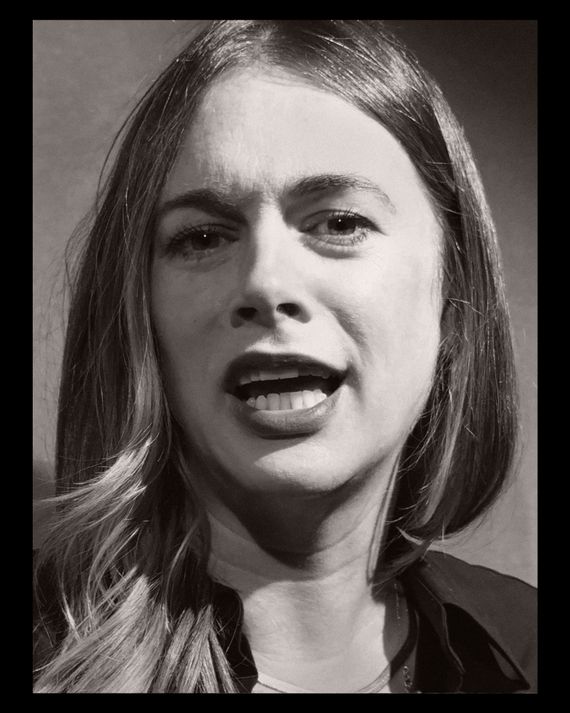

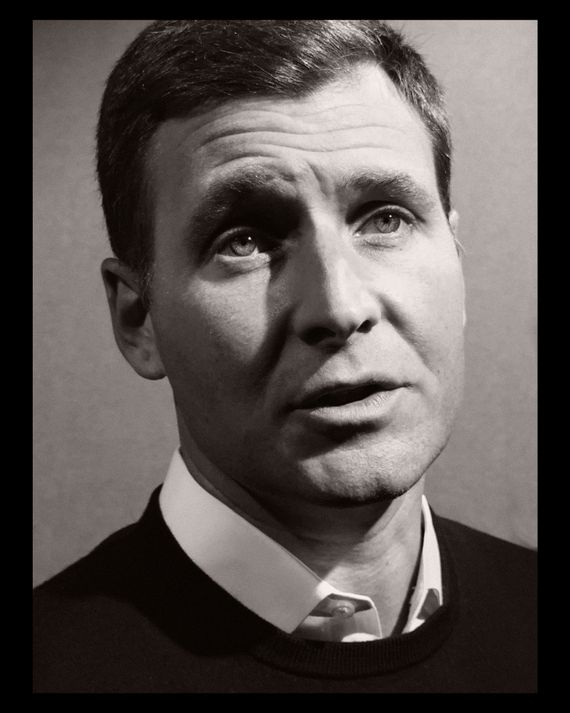

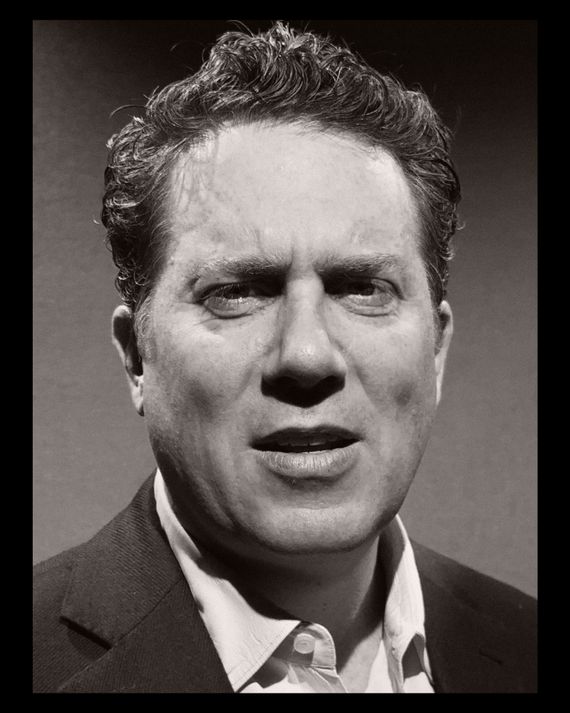

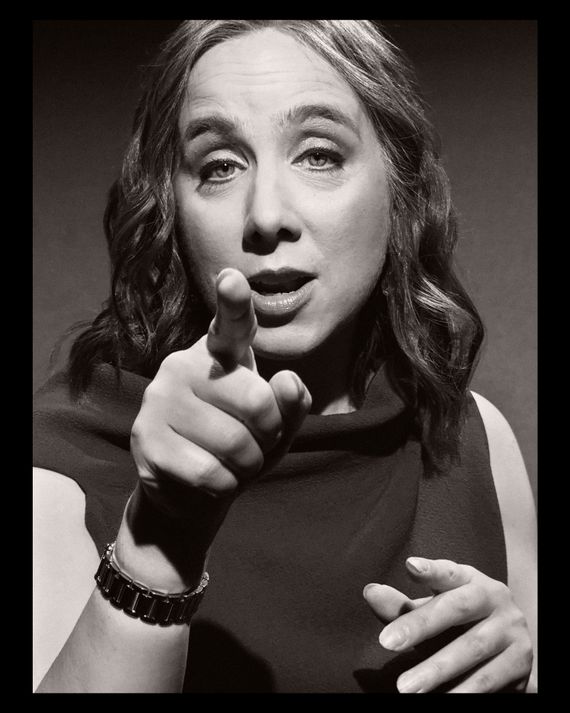

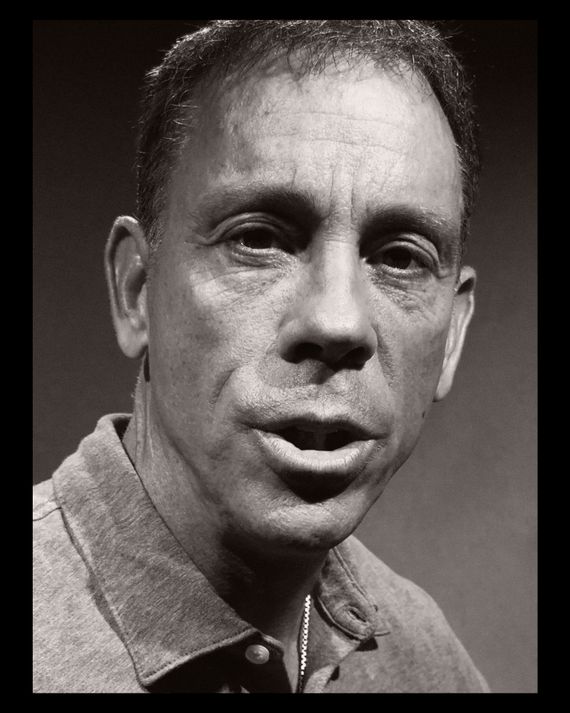

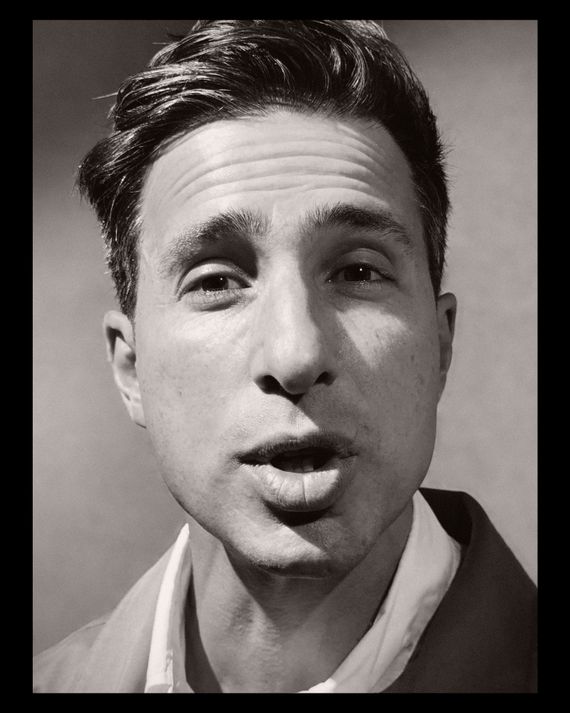

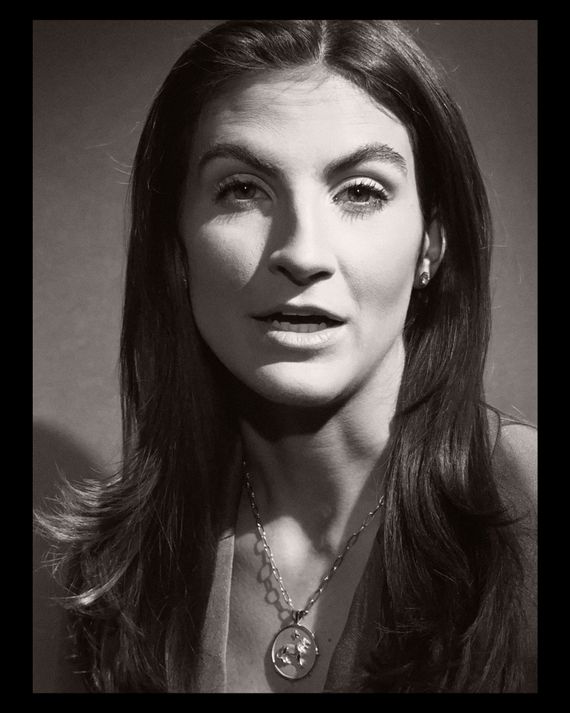

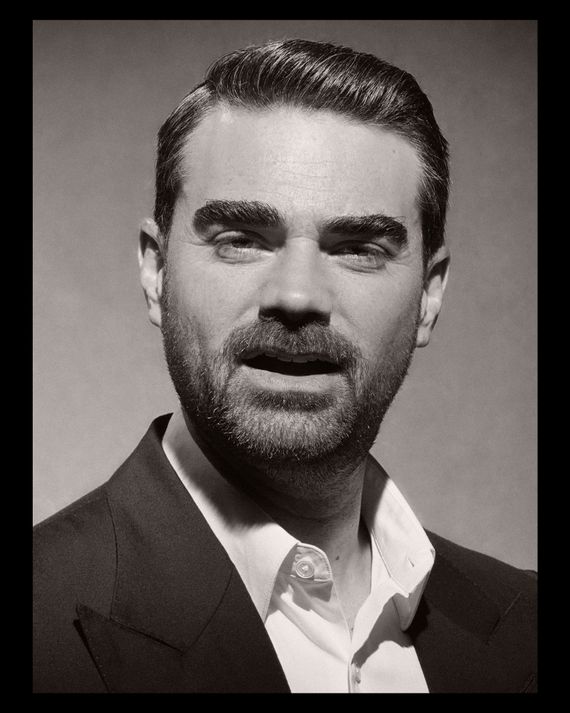

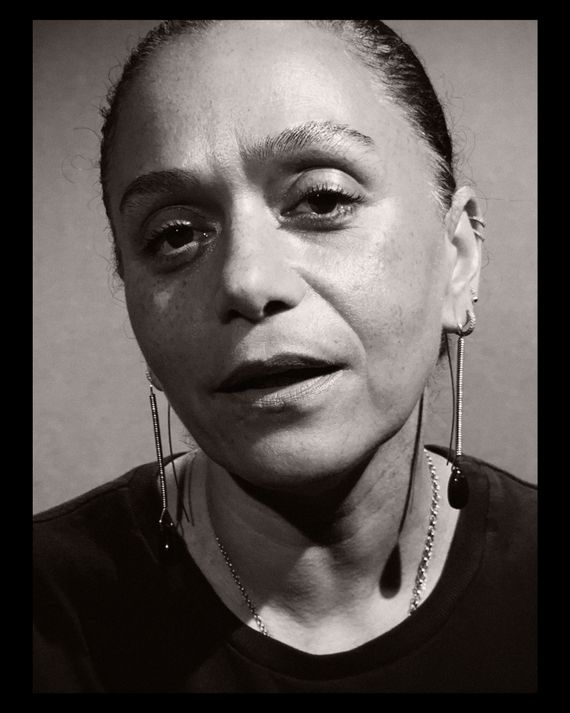

Portfolio by Paul Kooiker

保罗·库伊克的作品集

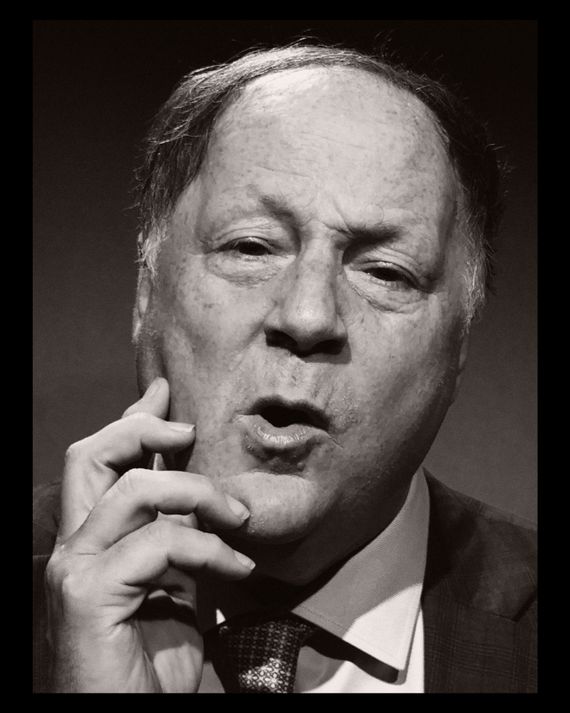

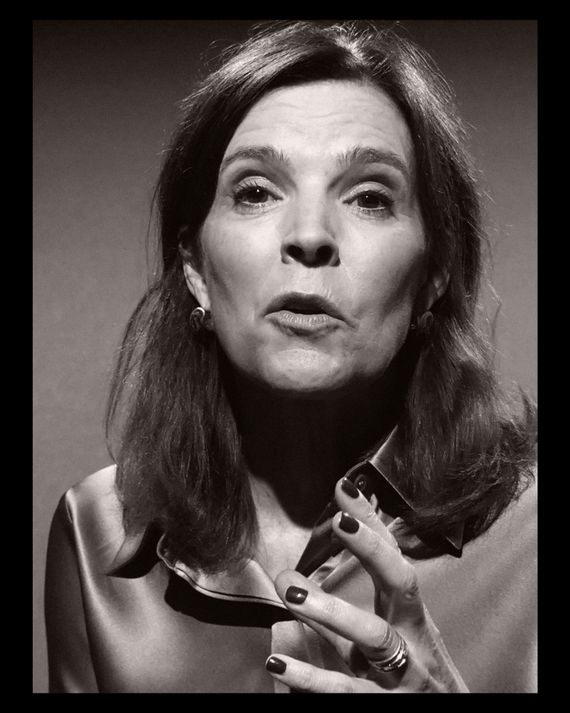

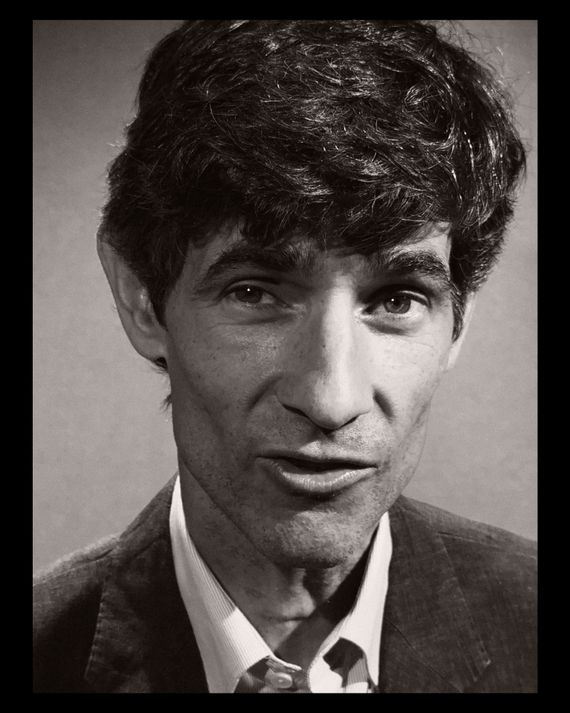

Photographed over 12 days in ten cities on the iPhone 16.

在十个城市用 iPhone 16 拍摄,历时 12 天。

盖尔·金,CBS 早间新闻联合主持人。

约翰·哈里斯,Politico 的联合创始人和全球主编。

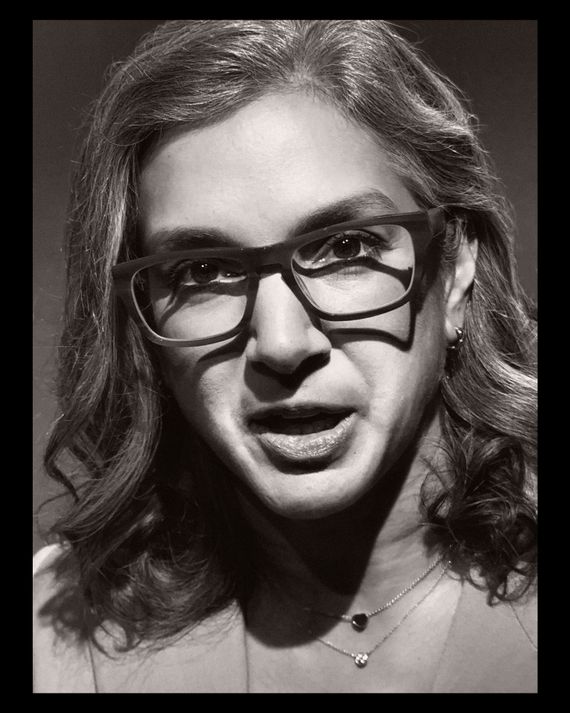

从左到右:哈米什·麦肯齐,Substack 联合创始人。伊姆兰·阿梅德,《时尚商业》创始人兼主编。

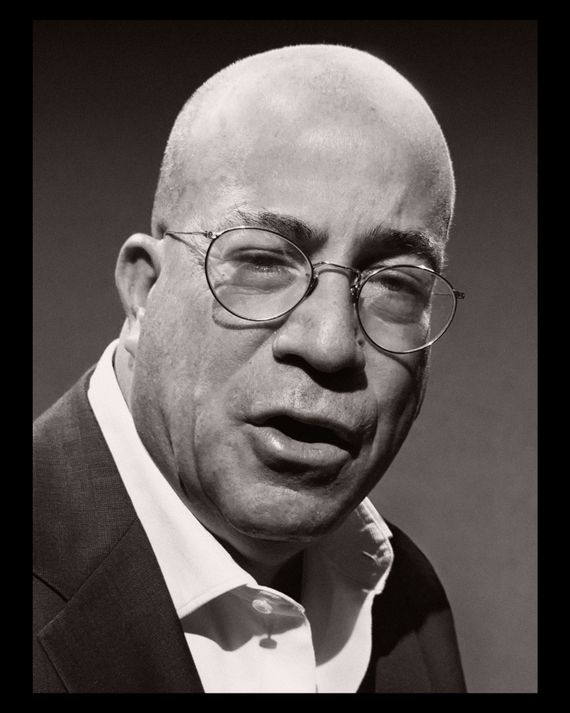

从左到右:杰夫·扎克,首席执行官,红鸟 IMI。拉迪卡·琼斯,主编,《名利场》。

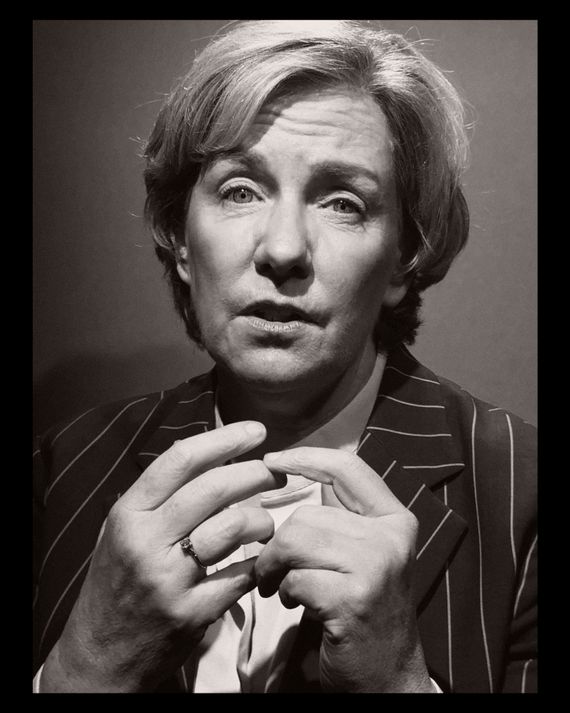

从左到右:比尔·欧文斯,执行制片人,CBS 的《60 分钟》。卡罗琳·瑞安,管理编辑,《纽约时报》。

从左到右:乔纳·佩雷蒂,BuzzFeed, Inc. 联合创始人兼首席执行官;贝茜·里德,《卫报》美国版编辑。

查拉马涅·塔·戈德,《早餐俱乐部》联合主持人;黑人效应播客网络创始人。

从左到右:布莱恩·戈德堡,Bustle Digital Group 首席执行官;乔安娜·科尔斯,《每日野兽》首席创意与内容官。

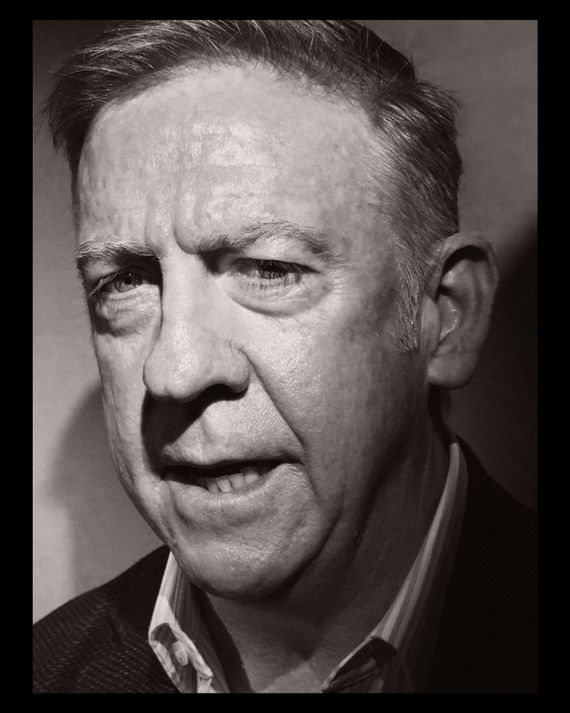

从左到右:斯蒂芬·恩格尔伯格,ProPublica 主编;安德鲁·罗斯·索金,《纽约时报》DealBook 创始人兼特约编辑;CNBC《Squawk Box》联合主持人。

艾玛·塔克,《华尔街日报》主编。

尼古拉斯·汤普森,《大西洋月刊》首席执行官。

Everybody Is Jealous of the New York Times.

人人都嫉妒《纽约时报》。

It’s a tale of two cities. It’s almost like it’s the one percent and the 99 percent,” says a journalist surveying the field beyond the Times’ walled garden. As the rest of the industry scrambles for scraps, the Times has become the Amazon of legacy media — an everything store for blue-state America’s information needs (and more). “They’ve got Wordle and all the journalism,” says Hamish McKenzie. “Almost all the journalism talent and quality gets sucked up because it’s becoming the megalith, the giant in the room that can’t be stopped.”

这是两个城市的故事。几乎就像是 1%和 99%之间的差距,”一位记者在观察《纽约时报》围墙外的情况时说道。随着行业其他部分争相争夺残羹冷炙,《纽约时报》已成为传统媒体的亚马逊——为蓝州美国的信息需求(以及更多)提供一切。“他们有 Wordle 和所有的新闻报道,”哈米什·麦肯齐说。“几乎所有的新闻人才和质量都被吸引过去,因为它正在成为一个巨头,房间里无法被忽视的庞然大物。”

“They sit on 10 million paid subs; that’s unlikely to dwindle. That’s just a very powerful base to operate from,” notes one rival editor-in-chief. “They figured it out first — how to make a killing off recipes and games that could sustain the rest of their journalism,” says former CNN boss Jeff Zucker. It’s gotten to the point that, according to one estimate, the Times now employs some 7 percent of newspaper journalists nationwide. “When other people are doing something better, they hire their people away,” says a digital media executive.

“他们拥有 1000 万付费订阅用户;这不太可能减少。这是一个非常强大的运营基础,”一位竞争对手的主编指出。“他们首先找到了办法——如何通过食谱和游戏赚取丰厚利润,以维持他们的其他新闻报道,”前 CNN 总裁杰夫·扎克说。根据一项估计,时报现在雇佣了全国约 7%的报纸记者,情况已经发展到这个地步。“当其他人做得更好时,他们就会挖走那些人,”一位数字媒体高管表示。

Right now, the Times is so far ahead it’s hard to imagine anybody catching up. “There’s a conversation that comes up all the time with people starting or working in journalistic enterprises, which is, ‘What’s going to be our Wordle?’” says Bari Weiss. And can anybody else do that? “Not to pick on the Times, but every answer to success can’t be, ‘Let’s point to the Times,’” says another media executive. “You’re not going to be able to replicate the Times’ success.” Just look at the new supersize app, which combines all of the paper’s many offerings. “It’s like, ‘Our newsroom of 2,000 people is just one of ten things you can be choosing,’” says an editor-in-chief.

目前,《纽约时报》遥遥领先,令人难以想象有人能够追赶上。“在与那些刚开始或在新闻机构工作的人交谈时,总会出现一个话题,那就是,‘我们的 Wordle 会是什么?’”巴里·韦斯说。还有其他人能做到这一点吗?“不是要针对《纽约时报》,但成功的每个答案都不能是,‘让我们指向《纽约时报》’,”另一位媒体高管说。“你无法复制《纽约时报》的成功。”看看这个新的超级应用程序,它结合了报纸的众多产品。“这就像是,‘我们的新闻编辑部有 2000 人,只是你可以选择的十个选项之一,’”一位主编说。

But Not Necessarily for Its Journalism.

但不一定是因为它的新闻报道。

“I envy their business model; I don’t envy their newsroom. I think it’s bloated and kind of self-indulgent,” says a top newspaper editor.

“我羡慕他们的商业模式;我不羡慕他们的新闻编辑部。我认为它臃肿且有些自我放纵,”一位顶级报纸编辑说道。

“They pivoted from being a newspaper for everyone to being a newspaper for their core reader,” says Bustle’s Bryan Goldberg. “From a purely business standpoint, that was the right decision, but I also think it made the world a much worse place, and that’s a difficult thing to reconcile.”

“他们从一个面向所有人的报纸转变为一个面向核心读者的报纸,”Bustle 的布莱恩·戈德堡说。“从纯商业的角度来看,这是正确的决定,但我也认为这让世界变得更糟,这是一件很难调和的事情。”

Some are eager to (anonymously) second-guess the Times’ business decisions, too. “They’ve been terrible with podcasts for the most part,” says one media executive. “They spent $550 million on The Athletic when they could have just spent $100 million and gotten all the best sportswriters. It’s like, Oh, you guys don’t know what you’re doing.”

有些人也急于(匿名)对《纽约时报》的商业决策进行猜测。一位媒体高管表示:“他们在播客方面大部分时间表现糟糕。他们花了 5.5 亿美元收购《体育新闻》,而本可以只花 1 亿美元就能得到所有最优秀的体育记者。就像是,你们根本不知道自己在做什么。”

But a lot of that just feels like sour grapes. “It’s amazing to me that they’re the piñata of American journalism,” says Stephen Engelberg. “Whatever they write, somebody’s constantly whacking. They do more good stories in a week than many of us do in months. And you have to tip your hat to people who can get inside the Supreme Court in real time. That’s really something.”

但很多听起来只是酸葡萄心理。“他们在美国新闻界就像一个打击靶,这让我感到惊讶,”斯蒂芬·恩格尔伯格说。“他们每周写的好故事比我们很多人几个月写的还要多。而且你必须向那些能够实时进入最高法院的人致敬。这真是了不起。”

“Part of the problem in the media business has been the collapse of brands, and the Times has managed to maintain its,” says Michael Wolff. For a journalistic buccaneer like Wolff, the operations of that brand machinery feel soul-crushing. “You want to work at the Times? I’d rather kill myself.” The feeling is likely mutual.

“媒体行业问题的一部分在于品牌的崩溃,而《纽约时报》设法保持了它的品牌,”迈克尔·沃尔夫说。对于像沃尔夫这样的新闻海盗来说,这种品牌运作的感觉令人窒息。“你想在《纽约时报》工作?我宁愿自杀。”这种感觉可能是相互的。

The Wall Street Journal Might Be the Only Real Rival to the Times Now.

《华尔街日报》可能是现在唯一真正的《纽约时报》竞争对手。

One of the most lauded legacy enterprises that is not the Times is The Wall Street Journal — and most of the credit goes to its editor, Emma Tucker, who arrived early last year and was immediately confronted with Russia’s arrest of reporter Evan Gershkovich. She also had to get up to speed on covering a presidential election in a country that isn’t hers while remaking a somewhat bloated and stultified newsroom into one closer to the lighter-on-its-feet U.K. model. And she somehow did it. “I think that they’ve passed the Washington Post,” observes one veteran journalist.

《华尔街日报》是最受赞誉的传统媒体之一,尽管它不是《纽约时报》,但大部分功劳归功于其编辑艾玛·塔克,她在去年初上任,立即面临俄罗斯逮捕记者埃文·格什科维奇的事件。她还必须迅速适应在一个并非她自己国家的总统选举报道,同时将一个有些臃肿和呆板的新闻编辑部改造成更接近灵活的英国模式。她不知怎么地做到了这一点。一位资深记者观察到:“我认为他们已经超越了《华盛顿邮报》。”

Her makeover of the paper into a livelier, more audience-conscious read has been widely praised. “I rarely considered The Wall Street Journal near the top of my ‘fun read’ list in the past,” says Timesman and CNBC co-anchor Andrew Ross Sorkin, but it’s become “a lot more interesting and readable. I think every day I find more features that are accessible and surprising. I feel the heat of what they’re doing. I feel it in the headlines.” New York Post editor-in-chief and fellow Rupert Murdoch employee Keith Poole enthuses, “She’s brought a way of telling a story from the headline down that’s much more instantly engaging and a much faster drumbeat of scoops.”

她对这份报纸的改造使其变得更加生动,更加关注读者,受到了广泛赞誉。“过去我很少把《华尔街日报》视为我‘有趣阅读’列表的前列,”《纽约时报》的安德鲁·罗斯·索尔金(Andrew Ross Sorkin)说,“但它变得‘更加有趣和易读。我觉得每天都能发现更多可接触和令人惊讶的特写。我能感受到他们所做事情的热度。我在头条新闻中感受到了这一点。’《纽约邮报》主编、鲁珀特·默多克的同事基思·普尔(Keith Poole)兴奋地表示:“她带来了一种从标题到内容讲述故事的方式,这种方式更加引人入胜,新闻的节奏也更快。”

From Elon Musk exposés to being early on Joe Biden’s cognitive decline, “she’s pissed off a lot of people along the way, but it’s a more interesting and surprising read now,” notes another editor. She had several advantages coming in, though: The Journal was early to having a paywall, which its business readers were willing to pay for (and expense). Since Murdoch bought it in 2007, it has become the national center-right quality newspaper. Which means people who can’t abide the Times can instead get the Journal. The L.A. Times and the Washington Post, meanwhile, have arguably been fighting for the same educated, blue-bubble reader.

从埃隆·马斯克的揭露到早期关注乔·拜登的认知衰退,“她在这个过程中惹恼了很多人,但现在的阅读体验更有趣、更令人惊讶,”另一位编辑指出。尽管如此,她在进入时有几个优势:华尔街日报早早就设立了付费墙,而其商业读者愿意为此付费(并报销)。自从默多克在 2007 年收购以来,它已成为全国性的中右翼优质报纸。这意味着那些无法忍受《纽约时报》的读者可以选择《华尔街日报》。与此同时,洛杉矶时报和《华盛顿邮报》无疑在争夺同样的受过教育的蓝色气泡读者。

And in the end, Tucker also got Gershkovich released.

最终,塔克也促成了格尔什科维奇的获释。

8 Shout-Outs 8 个致敬

Who else is having a good year?

还有谁在过得不错呢?

2Way 双向

“I was at a dinner party and was told that someone well known was told the only person you have to read to understand what’s happening right now is Mark Halperin. So I immediately log on to 2Way and I’m like, Wow, it’s like $5,000 or $3,000. He does these nightly Zoom calls, which are like live cable television but with audiences that he’s curating. I was just sitting at home watching CNN at my parents’ house and thought, Why am I doing this? I should’ve been dialing into his Zoom and hearing from him and all these experts whom he’s bringing to the table about whether Biden was going to step aside. It was awesome. Nancy Pelosi’s former chief of staff was one of the speakers, then he went to Jill Abramson … I’ve been kind of blown away by this, honestly, because it feels like something really new and really authoritative.” — Jessica Lessin

“我参加了一个晚宴,听说有位知名人士说,想要理解现在发生的事情,唯一需要阅读的人就是马克·哈珀林。所以我立刻登录了 2Way,发现费用大约是 5000 美元或 3000 美元。他每晚进行 Zoom 视频通话,就像直播的有线电视,但观众是他精心挑选的。我当时在父母家看 CNN,心想,为什么我要这样做?我应该拨打他的 Zoom,听听他和他邀请的专家们关于拜登是否会退位的看法。这真是太棒了。南希·佩洛西的前幕僚长是演讲者之一,然后他又请到了吉尔·阿布拉姆森……老实说,我对此感到非常震惊,因为这感觉像是一些真正新颖且权威的东西。” — 杰西卡·莱辛

The NBA NBA

“No one is having a better year than the NBA right now. They’ve just completed a historic negotiation that makes their media rights almost as valuable as the National Football League’s own media package. And they have an incredible business model with proven, engaged owners, and they — the owners and Adam Silver — have done an excellent job of convincing the three or so biggest entertainment companies that their sport is vital to long-term survival in the industry.” — Jon Kelly

“目前没有哪个行业的表现能比 NBA 更好。他们刚刚完成了一项历史性的谈判,使他们的媒体版权几乎与国家橄榄球联盟的媒体套餐同样有价值。而且他们拥有一个令人难以置信的商业模式,拥有经过验证的、积极参与的老板们,老板们和亚当·西尔弗一起,成功地说服了三家左右最大的娱乐公司,认为他们的运动对行业的长期生存至关重要。” — 乔恩·凯利

The Ringer 响铃者

“It seems to be having a lot of fun, and they’re trying a lot of stuff. It feels like they’ve got momentum.” — Sam Dolnick

“他们似乎玩得很开心,尝试了很多东西。感觉他们有了势头。” — 山姆·多尔尼克

Ezra Klein and Bari Weiss

埃兹拉·克莱因和巴里·韦斯

“The stars of 2024. This is their year.” — Matthew Yglesias

“2024 年的明星。这是他们的一年。” — 马修·伊格莱西亚斯

The Daily Wire 每日电线

“I think the way they’ve been able to leverage cultural commentary and expand beyond the traditional audience that consumes political content — that’s pretty enviable.” — Glenn Greenwald

“我认为他们能够利用文化评论并扩展到传统政治内容受众之外的方式——这非常令人羡慕。” — 格伦·格林沃尔德

Barstool Sports 巴斯图尔体育

“I mean, look, it’s so far afield from the way I approach the world, but they totally have figured out how to capture the attention of a particular cohort and generation of people.” — A top journalist

“我的意思是,看看,这与我看待世界的方式相去甚远,但他们完全找到了吸引特定群体和一代人的注意力的方法。” — 一位顶级记者

Call Her Daddy 叫她爸爸

“What Alex Cooper’s building with her company — whenever you’re able to take one platform, which is the Call Her Daddy podcast, and turn that into a network that has other podcasts on there that are just as big — you have to salute that.” — Charlamagne Tha God

“亚历克斯·库珀通过她的公司所建立的事业——无论何时你能够将一个平台,即《Call Her Daddy》播客,转变为一个拥有其他同样受欢迎播客的网络——你都必须为此致敬。” — 查拉梅恩·萨尔戈德

Where These Insiders Get Their Gossip Fix.

这些内部人士从哪里获取八卦信息。

“The group chats, the private texts, voice memos. Don’t ever put anything in writing.” — Alison Roman • “I think I would say from the source.” — Michael Wolff • “Sometimes my colleagues and partners, but I have about three or four people I talk to almost every day.” — Jon Kelly • “The parties I host.” — A media executive • “Well, I get a lot of my gossip from Ben Shapiro.” — Jeremy Boreing • “The New York Post.” — Gus Wenner • “I feel like the D.C. bureau of the New York Times has better gossip than the one in New York. Always. Anybody who’s not in the main office knows more than the people there or has gossip about it. They’re all trying to figure out what’s happening all the time.” — A top journalist • “Group chats. Word of mouth on the street. Instagram.” — Mel Ottenberg • “I read our staff Slack channels, so I’m vicariously reading Lainey Gossip and the Daily Mail. Then obviously I have group chats, and most of those are on Signal.” — Radhika Jones • “Cocktail parties, of course.” — Ramesh Ponnuru

“群聊、私人短信、语音备忘录。永远不要把任何事情写下来。” — 艾莉森·罗曼 • “我想我会说来自源头。” — 迈克尔·沃尔夫 • “有时是我的同事和合作伙伴,但我大约有三到四个人几乎每天都在交流。” — 乔恩·凯利 • “我举办的聚会。” — 一位媒体高管 • “好吧,我从本·沙皮罗那里获得了很多八卦。” — 杰里米·博林 • “《纽约邮报》。” — 古斯·温纳 • “我觉得《纽约时报》华盛顿分社的八卦比纽约的更好。总是如此。任何不在总部的人都知道比那里的员工更多,或者有关于它的八卦。他们都在试图弄清楚发生了什么。” — 一位顶级记者 • “群聊。街头的口耳相传。Instagram。” — 梅尔·奥滕伯格 • “我阅读我们的员工 Slack 频道,所以我间接地在阅读 Lainey Gossip 和《每日邮报》。然后显然我有群聊,其中大多数是在 Signal 上。” — 拉迪卡·琼斯 • “鸡尾酒会,当然。” — 拉梅什·波努鲁

Is the Future of Journalism in Your Inbox?

新闻的未来在你的收件箱中吗?

Substack launched in 2017, offering journalists tired of giving all their insights away for free on what was then known as Twitter (or of trying to entice readers to their paywalled blog) a plug-and-play service to launch email newsletters people could pay to subscribe to. And now even Tina Brown has signed on.

Substack 于 2017 年推出,为那些厌倦了在当时被称为 Twitter 的平台上免费分享所有见解的记者(或试图吸引读者订阅其付费博客的记者)提供了一种即插即用的服务,帮助他们推出人们可以付费订阅的电子邮件通讯。现在,连蒂娜·布朗也加入了。

But the email pile-in goes beyond the solo proprietors, whether zoomer or boomer. With the decline of social media in general as a way to distribute news, even the legacy news operations got in the game, launching specialized newsletters hoping to drive traffic back to their paywalled websites or as a sort of concierge content-delivery service for their subscribers interested in a particular topic or writer. “I’m bullish because it’s relatively low cost and easy to do, and a great voice is all you really need,” says the Times’ Sam Dolnick. “It’s a direct relationship between the writer and reader.”

但电子邮件的涌入不仅限于独立经营者,无论是年轻一代还是老一代。随着社交媒体作为新闻传播方式的整体衰退,甚至传统新闻机构也开始参与其中,推出专业化的新闻通讯,希望能将流量引回他们的付费网站,或者作为一种为对特定主题或作者感兴趣的订阅者提供的礼宾式内容传递服务。“我对这个持乐观态度,因为这相对成本低且易于操作,而真正需要的只是一个出色的声音,”《纽约时报》的萨姆·多尔尼克说。“这是一种作家与读者之间的直接关系。”

But for a newsletter to work, it has to give that reader something they think they need — intellectual companionship or insight or entertainment. Ben Shapiro calls such products “textual extensions of a podcast.”

但要使新闻通讯有效,它必须提供读者认为他们需要的东西——智力上的陪伴、洞察力或娱乐。本·沙皮罗称此类产品为“播客的文本延伸”。

“Somebody like Nate Cohn, who is our polling expert — you can read a newsletter that might be just 800 words and come away feeling smarter,” as Carolyn Ryan puts it.

“像我们的民调专家内特·科恩这样的人——你可以阅读一篇可能只有 800 字的通讯,读完后会觉得更聪明,”卡罗琳·瑞安这样说。

Email isn’t glamorous. “I hate the name, and somebody’s going to have to come up with something sexier. The term newsletter sounds like something that comes out of a church basement,” says Graydon Carter, whose publication, Air Mail, has brought more magazine glamour to emails than any of its peers. “But the brilliant thing about it is it’s free home delivery, and there’s no printing or shipping. If this sort of technology had existed, nobody would ever have invented a magazine or a newspaper.” Everybody gets email and opens at least some of it. “I think the most moronic thing I’ve ever heard, in terms of conventional wisdom in media, was that we reached peak newsletters,” says Axios’ Jim VandeHei.

电子邮件并不华丽。“我讨厌这个名字,必须有人想出更性感的名字。‘通讯’这个词听起来像是从教堂地下室里出来的,”格雷登·卡特说,他的出版物《航空邮件》为电子邮件带来了比任何同行都更多的杂志魅力。“但它的精彩之处在于,它是免费的送货上门,没有印刷或运输。如果这种技术早就存在,没人会发明杂志或报纸。”每个人都能收到电子邮件,并且至少会打开其中的一部分。“我认为我听过的最愚蠢的媒体传统智慧就是我们达到了通讯的巅峰,”Axios 的吉姆·范德海说。

So How Is Going Solo Going?

那么独自一人过得怎么样?

In some ways, the Substack career track has taken the place of the dream of the low-overhead, self-sustaining blog. As Substack’s Hamish McKenzie attests, it means writers “being able to make money directly from the readers instead of hoping that they’ll amass some kind of audience from which will trickle down some advertising dollars or some brand deals or something like that.”

在某种程度上,Substack 的职业道路取代了低成本、自给自足博客的梦想。正如 Substack 的哈米什·麦肯齐所言,这意味着作家“能够直接从读者那里赚钱,而不是寄希望于他们能积累某种观众,从中获得一些广告收入或品牌交易之类的东西。”

There’s no question it works for some people. “I know a lot of writers who have been able to leave their media jobs because they can have a Substack and do really, really, really well, and sometimes they make more money,” says Willa Bennett of Seventeen and Cosmopolitan.

毫无疑问,这对某些人有效。“我认识很多作家,他们能够辞去媒体工作,因为他们可以拥有一个 Substack,并且做得非常非常好,有时他们赚得更多,”《十七岁》和《时尚》杂志的 Willa Bennett 说。

But most people don’t have enough of a preexisting following to make a living off it.

但大多数人没有足够的现有粉丝来以此谋生。

“It’s great for Casey Newton, but there’s not that many people it’s great for,” says one media executive. “My understanding of it is that 5 percent of the writers are making 90 percent of the money, which I don’t find surprising,” says The Daily Beast’s Joanna Coles. Beyond subscriptions, that money includes sponsorships, ads, the works — like a mini-magazine.

“这对凯西·纽顿来说很好,但对其他人来说并没有那么好,”一位媒体高管说。“我了解到,5%的作家赚取了 90%的收入,这让我并不感到惊讶,”《每日野兽》的乔安娜·科尔斯说。除了订阅,这笔钱还包括赞助、广告等,像是一个迷你杂志。

And then there is the issue of quality control. “Some of them are fantastic, and some of them could really use editors and infrastructure,” notes one top editor. “And the trouble with platforms that are distributing them is that there’s not that kind of editorial infrastructure to vet, to push back, to say, ‘Wait a minute — is that actually a story?’ or ‘Is that headline fair?’ There just aren’t enough people to be the checks and balances. So in some ways, it’s much more similar to social media.”

然后还有质量控制的问题。“其中一些非常出色,而另一些则确实需要编辑和基础设施,”一位顶级编辑指出。“而分发这些内容的平台的问题在于,缺乏那种编辑基础设施来审核、反驳,或者说,‘等一下——这真的算是一个故事吗?’或者‘这个标题公正吗?’根本没有足够的人来进行制衡。因此在某种程度上,这更像是社交媒体。”

Some People Fork Out For …

一些人愿意花钱订阅的新闻通讯……

“I pay for Emily Sundberg’s and I pay for Rachel Karten’s.” — Alison Roman • “I pay for Drop Site News, which is the Substack started by my old colleagues from The Intercept. I pay for Zeteo, and I pay for Slow Boring.” — Betsy Reed • “I subscribe to Hunter Harris, Notes From Auntie’s Desk, Emilia Petrarca, Leandra Medine, Amy Odell, and a few others.” — Eva Chen • “John Ellis, Andrew Sullivan, Tina Brown, Joe Klein, Judd Legum, Roger Pielke Jr.” — Matt Murray • “I pay for Nate Silver, Noah Smith, Cartoons Hate Her, Tim Lee.” — Matthew Yglesias • “I pay for Ben Thompson’s newsletter.” — Nicholas Thompson • “I don’t pay for Opulent Tips, but it’s absolutely my favorite. Emily Sundberg. Casey Lewis. Amy Odell. Emilia Petrarca.” — Willa Bennett • “I pay for Andy Borowitz. And The Free Press.” — Graydon Carter • “Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Steve Schmidt.” — Gayle King • “I appear to be paying for probably 30 or 40 different Substacks, which I can’t figure out how to not pay for.” — Joanna Coles

“我为艾米莉·桑德伯格和瑞秋·卡滕付费。” — 艾莉森·罗曼 • “我为《投递站新闻》付费,这是我在《拦截者》工作的老同事们创办的 Substack。我为 Zeteo 付费,也为 Slow Boring 付费。” — 贝茜·里德 • “我订阅了亨特·哈里斯、阿姨的桌子笔记、埃米莉亚·佩特拉卡、莱安德拉·梅迪内、艾米·奥德尔和其他一些人。” — 伊娃·陈 • “约翰·埃利斯、安德鲁·沙利文、蒂娜·布朗、乔·克莱因、贾德·莱根、罗杰·皮尔克小。” — 马特·穆雷 • “我为内特·西尔弗、诺亚·史密斯、卡通恨她、蒂姆·李付费。” — 马修·伊格莱西亚斯 • “我为本·汤普森的通讯付费。” — 尼古拉斯·汤普森 • “我不为奢华小贴士付费,但它绝对是我最喜欢的。艾米莉·桑德伯格。凯西·刘易斯。艾米·奥德尔。埃米莉亚·佩特拉卡。” — 威拉·贝内特 • “我为安迪·博罗维茨和《自由新闻》付费。” — 格雷登·卡特 • “卡里姆·阿卜杜尔-贾巴尔和史蒂夫·施密特。” — 盖尔·金 • “我似乎为大约 30 或 40 个不同的 Substack 付费,但我不知道怎么才能不付费。” — 乔安娜·科尔斯

Get a Posse of Name-Brand Writers to Sell Their Wares Together and You Have … Puck

聚集一群知名品牌的通讯作家共同销售他们的产品,你就得到了……《帕克》

Nearly all the people interviewed for this project read at least one of the view-from-inside-a-particular-industry newsletters (from Hollywood to fashion to the art market) that make up the subcription-based Puck. “They have a lot of swagger. They have been successful in creating buzz. I know people who despise them. I’m meeting a lot of executives and studios and other places who don’t like them, but they consume them. They’re a little sloppy, too, and I wonder how much there is there,” says one media executive. Four more perspectives from four more media executives:

几乎所有参与此项目的受访者都阅读过至少一份来自特定行业内部视角的通讯(从好莱坞到时尚再到艺术市场),这些通讯构成了基于订阅的 Puck。“他们非常自信,成功地制造了话题。我知道有些人非常厌恶他们。我遇到了很多不喜欢他们的高管、制片厂和其他地方的人,但他们还是会消费这些内容。他们有点马虎,我在想这其中到底有多少价值,”一位媒体高管说道。以下是四位媒体高管的四个不同观点:

1. It’s Chatty. 它很健谈。

“I’m surprised by how much I read Puck. They’ve broken news, but that whole newsletter style — maybe that’s the future of what writing’s going to be now, a little conversational.”

“我对自己阅读 Puck 的频率感到惊讶。他们报道了新闻,但那种整个通讯的风格——也许这就是写作未来的样子,更加对话化。”

2. It’s Gossipy. 它很八卦。

“I think they know their audience and are doing work that you don’t find elsewhere. But it’s really just for wicked little gossip. And I think that most people are gossips, or at least most people in our industry. So to have somebody who’s just like, ‘Here’s some shit to talk about somebody,’ it’s kind of fun. And I think that’s a thing I could see building a business around. That’s not the kind of journalism that I get most excited about or aspire to, but I think that there’s a lane for that.”

“我认为他们了解自己的受众,并且做着你在其他地方找不到的工作。但这真的只是一些恶毒的小八卦。我觉得大多数人都是爱八卦的,或者至少我们行业的大多数人都是。所以有一个人就像是‘这里有些可以谈论某人的事’,这有点有趣。我认为这是一种我可以看到围绕其建立商业的方式。这不是我最感兴趣或渴望的那种新闻报道,但我认为这确实有其市场。”

3. It’s Maybe Too Much Fun to Be True.

也许这太好玩了,难以置信。

“I believe most of their reporting. I mean, in some ways, they’ve gotten things massively wrong that involve me, so maybe I shouldn’t put that there.”

“我相信他们的大部分报道。我的意思是,在某些方面,他们在涉及我的事情上犯了巨大的错误,所以也许我不应该把这个放在那里。”

4. And Private-Equity Financed.

4. 以及私募股权融资。

“They have taken on a lot of money, and I think it’s a little bit replicating the model of the previous decade. You’re just trying to outrun the money, but it eventually catches up.”

“他们已经获得了很多资金,我认为这有点像在复制上一个十年的模式。你只是在试图超越资金,但最终它会追上来。”

There’s No Business Like the Scoop Business.

没有比独家新闻更好的生意。

At a moment with no shortage of content, breaking news is what sets publications, especially the upstarts, apart.

“The biggest message is to get scoops. I just think that the talent dynamics in the industry are changing so fast, and that the value of doing pretty good work goes down every day, and that you need to either play a really essential supporting role or really break out, and there’s less and less space between those two things,” says Semafor’s Ben Smith.

“It is a great time to be in the excellent-journalism business, and it’s a shitty time to be in the mediocre-journalism business. I think there is a great business in hit-driven journalism — the biggest scoop, the biggest investigative story, maybe the top 20 percent of what great journalists and news organizations are doing,” says The Information’s Jessica Lessin. “The reality — and it’s not an easy reality to contend with — is there’s not a great business for the 80 percent.”

“I said to everyone here after a kind of mediocre pitch meeting: ‘Just to remind everyone, this right here is the business,’” says Bari Weiss of The Free Press. “‘There’s not another secret business. The business is the stories that you pitch and the scoops that you bring to me, and if they’re not good, the business will not grow.’”

But scoops don’t live very long anymore.

“We’re in this age when news breaks — which are the great bragging rights of any journalist — are so ephemeral,” says Janice Min. “They disappear almost instantly because everyone else jumps in and has a hot take.”

Inside in the Newsroom

What Happened to DEI?

The decadelong effort to diversify historically white and male newsrooms seems to have slowed. While some participants reaffirmed the idea behind DEI — “If your ambition is to really cover the world as it really is,” says Times assistant managing editor Sam Sifton, “then you need to have a newsroom that looks like the world outside” — there was a broad sense that the focus has shifted. “No one cares about diversity,” notes a (non-white) executive. “No one’s going to be like, Oh my God, another white guy getting the job. I think we took two steps forward, one step back.”

One executive says, “I think being performative about it is less of a thing now than it was two years ago, and thank God.” Instead, as a (white) executive puts it, those being hired are candidates who “are qualified for these jobs rather than just because they are not a white male.”

But one downside of DEI was that not everyone brought in under its impetus felt supported. One (white) editor says, “I have a lot of friends, especially some Black people in publishing who I am close with, who feel that there was a real tokenization. I have a friend who’s a literary agent who was brought into a large talent house and just left to start her own boutique thing. She was really being called on to bring in a certain kind of perspective — the ‘diverse thing.’ And that’s not really what her focus is.”

The Kids Are Too Soft.

Entry-level journalists “are not nearly as talented as the people ten and 15 and 20 years ago,” insists one newspaper vet. There are lots of reasons that may be the case. “It used to be that you would give someone the advice, ‘Go work for a small-town paper and then come to me,’” says Bari Weiss. “Well, they’re all gone.”

Combine that with the pandemic and the rise of WFH and you get young staffers who never had a chance to be mentored. “They’re probably maybe a little less qualified because they’re less trained; the whole attitude is less servile than it used to be,” notes an editor. “You have people who are — I don’t want to say working fewer hours, but the mode of dues paying has changed a lot.”

One executive expressed frustration with Gen Z this way: “They want everything right away. They want everything fast. They’re super-ambitious in the wrong ways. The people that seem to me to succeed are the ones that just do good work, really push themselves, and assume the right people are going to notice. And guess what? The right people always notice. The stuff you never want to deal with is somebody who’s been there for nine months already asking what your long-term, seven-year plan is. It’s like, ‘You just got here. I don’t have a plan for you yet.’” Another editor-in-chief carps, “My biggest pet peeve is when it feels like I’m the teacher and they’re in sixth grade doing a homework assignment.”

The Bosses Are Feeling Bossy Again.

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a group of owners and managers, the rise of media unions over the past decade was treated mostly as a nuisance.

“I’ve always been supportive of unions, but I think the unions today are different and the guilds today are different,” says one executive. “They more mirror the activists’ posture on social issues and everything else.” The New York Times, as usual the industry bellwether, has clamped down on employee dissent under executive editor Joe Kahn after a staff revolt forced the ouster of “Opinion” editor James Bennet in 2020. A top newspaper editor says, “You have to know where to draw the line in a news organization between activism and professionalism. Kahn has finally drawn a line with that, and good for him.” Other organizations have struggled with the same issue. “You see what happened at the Washington Post; essentially, it’s anarchy,” says an anonymous executive. “The staff took over the publication and started dictating moves.”

Outside the activist front, some felt unions hadn’t delivered to their members. Nearly everyone recognized that management’s relationship to staff has probably changed permanently, at least compared with when interns were forced to work for free and assistants were expected to dog-sit for their bosses on weekends and worse. “You could just make people do whatever, whenever,” says Janice Min of the go-get-me-a-salad days of magazine editors pushing around their underlings. “Now, there’s just a much greater sense of boundary.” Still, there was some nostalgia for a time when a boss could push their charges to the limit. “I’m not saying you have to come to the office, but the people who do the best work — all of them — work really hard all the time. And you can’t say that anymore,” says an executive.

As with DEI, there is a sense, at least among managers, that, in the face of larger disruptions, the media labor revolution has gone as far as it is going to go. Starting wages have been raised, severance deals were better formalized, rules were negotiated as to what happens to the TV or film rights to an employee’s articles. But many executives suggest you can squeeze only so much out of a barely profitable business.

“Between the years, like, 2016 and 2021, the relationship between employers and employees shifted, and it’s shifted back, basically,” says one editor-in-chief. “That was a temporary phenomenon that really strikes me as over.”

What They Wish They Could Tell Their Staff.

“Journalism with a capital J is no good to anyone if nobody’s reading it.” — Emma Tucker • “The newsroom has to understand that it needs to align itself with the wider business goals. It can’t operate in isolation. We’re in such a fight for everyone’s time, and with paid subscription, we’re also in a fight for their money. Every editor is probably thinking, when they’re assigning something now, What is the ROI on this?” — Janice Min • “You want to write about Hamas in Israel? No one’s going to advertise against that. If you write a story about a female entrepreneur who’s made it up from poverty, I can sell infinite ads.” — Top editor No. 1 • “Thousands of people would kill for these jobs.” — Top editor No. 2 • “This job is really, really hard, and you don’t do it by sitting at a desk text-messaging.” — Top editor No. 3 • “Could be worse. You could be in academia.” — No. 4 • “It’s a hard job and it takes a lot of hours and you don’t always get clapped on the back and not everybody gets a sticker.” — No. 5

The Subject That Divided the Newsroom: Israel and Palestine.

In the year since October 7, leaders of news organizations have had to defend their coverage, not only to the readers, but also to their staff.

“I worried constantly last fall over alienating our contributors, our readers, and especially our colleagues. The past year has helped me learn and defend the position that we don’t all stand at exactly the same place on the left, and it’s perfectly healthy to follow the voices of our writers and help them to best articulate their beliefs. I also feel proud — I’m not joking when I say this — that no one has quit because of what we’ve done.” — Emily Greenhouse

“The most divisive issue internally in the last decade, more so than George Floyd.” — A digital media executive

“I have never experienced anything as intense as that moment, and I’ve been leading newsrooms for a long time. The depth and intensity of emotion, and the microscopic scrutiny of every word and every headline, is like nothing I’ve been through.” — A top editor

“Breaking through the individual personal circumstances that people are feeling and the framing and different degrees of activism people bring to the most fraught subject in the world — and finding a way to talk to people directly about those things in an honest way that makes clear your expectations without them feeling challenged, threatened, or that you have an agenda to drive — it’s very hard.” — An editor-in-chief

“This story is a different level. There’s no question about it. I think you have to be extra careful in the words you use and the way you tell the story.” — Gayle King

“It’s really, really difficult to cover a war when you only have access to one side. And so the lack of on-the-ground reporting from Gaza is really, really a handicap.” — Stephen Engelberg

“Every subject became politicized. Everything from our fashion coverage to our art coverage to our restaurant coverage became proxy for that war.” — A top editor

“I’m going to skip that one.” — An editor-in-chief

What Became of Media Moguldom?

Throughout the 2010s, the media business was a minter of great fortunes, and its proprietors — Rupert Murdoch, Barry Diller, Si Newhouse, etc. — were powerful, influential, and rich in the model of Citizen Kane. In the subsequent tumult of managed media decline, nobody has really replaced them. “It doesn’t feel like there are the kind of individuals wielding huge power in the way that they once seemed to loom over not just the industry but the culture,” says a top editor. “It feels like the older 70s-and-up crowd is kind of heading toward being done soon, but nobody really knows who the 50s and 60s people are,” says one media exec. People of that generation who made a play for it, like Jonah Peretti and Vice’s Shane Smith, have been humbled.

It’s not that there aren’t moguls. It’s just that they have less swag. “Technically, in terms of the reach of assets, I mean, it would be the Roberts family,” which owns Comcast, “or [Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David] Zaslav, I suppose, just by holding more assets and by holding a larger audience,” says Michael Wolff. “But there’s no resemblance to the executives who once ran this business.” “Graydon Carter, Lorne Michaels — you knew who all of them were,” says a media executive. “Richard Plepler. And they were all friends, and they all felt like they were running New York in a lot of ways. And I don’t know who that is anymore.”

Is Rupert Murdoch Still Powerful?

Yes: “The source of his power is Fox News, The Wall Street Journal, and the New York Post. It’s just an unbeatable combination that those three properties have a stranglehold on conservative thought in America.” — Jeff Zucker

No: “Well, that’s completely idiotic. Just showing the fact that nobody knows shit about what is going on in this business. First thing, Murdoch is 93 years old and barely sentient. Secondly, much of the empire that Murdoch had, hello, was sold off in 2018, which somehow people don’t quite focus on. He continues to have Fox News, which continues to be a significant voice in American politics, of course. But it is a less significant voice than it once was and will continue to be ever lesser — No. 1, because it’s in the cable-television business, which is in fast decline, and No. 2, because there actually are now real-time meaningful competitors in the conservative media space anyway. On top of which, what is left of the Empire is under enormous, enormous internal stress.” — Michael Wolff

Elon Musk Definitely Is.

“He’s the richest man in the world, who controls this massive platform that has a huge impact on what information and what media sources people are exposed to. And he has however hundreds of millions of followers himself, and he is actively and openly campaigning for Trump to be elected president. The degree of his power, it’s just mind-boggling and not in a good way.” — Betsy Reed

“He has a massive platform, and he exploits the shit out of it.” — Jim VandeHei

“The source of his power is his willingness to use it at the expense of his business to move politics in the short term.” — Ben Smith

“In 2016, if Rupert Murdoch had advocated for a VP candidate to Donald Trump, that person probably would’ve become the VP. He did that this time with Doug Burgum, and Trump didn’t pick Burgum. Ultimately, he was listening much more to the Elon Musks and Peter Thiels of the world.” — Kaitlan Collins

The Rise of the Billionaire Media Mogul Hobbyist.

There have always been wealthy people who want the status, influence, and attention you get from press ownership. “You’re asking if vanity and ego are still a thing in the world, and they will always be,” says one executive. The difference today is that media properties are no longer very good businesses, which means they often attract the interest of a different kind of rich person — either charitable or, possibly, delusional. Both types have a mixed record of late.

“I don’t think they’re serious players in the business sense,” says Hamish McKenzie of the current class of media benefactors. “I think they’re just owning — they’re picking up formerly prestigious brands as trophies for their shelves.” Billionaire ownership “keeps some people employed, and it keeps these loved institutions alive in some ways,” he says. But the publications supported like this “are mostly just on life support. They’re not actually major cultural players anymore.”

A billionaire owner “certainly makes it easier to have time to figure out your options,” says Politico’s John Harris. Because of that, a wealthy white knight is something many people working for financially shaky high-status operations are hoping for. “Someone will always take their money,” says Janice Min, likening it to the Medicis’ patronage.

But eventually, the good feeling wears off and the Medicis begin to resent their endless check writing to self-regarding journalists unwilling to adapt. “I haven’t really seen many billionaire benefactors who are kind of indifferent to the business performance of the property,” says Harris. “That’s just not the way it works,” adds an executive. “Marc Benioff wants Time to make money. People don’t get that because they think people much richer than them stop caring about money. Actually, that’s not the case. It’s people who are much richer than them who care obsessively about money.” Though they are often more patient than, say, venture-capital firms, eventually their charitable impulse runs low. “You don’t become a billionaire by letting your properties lose money indefinitely,” notes another executive.

Besides, having such support can, in that sense, be stifling to the business model. “The Washington Post and the L.A. Times are obviously the real case in point here,” says an editor-in-chief, “where billionaire ownership meant they never really took seriously building a business. And at some point, the billionaires get bored with that.”

“Just once, I would like to see a billionaire-backed business model in media, as opposed to just a billionaire subsidizing a broken business model,” says Jeremy Boreing.

Why Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong Hasn’t Turned Around the L.A. Times.

“It’s high on my list of organizations that have stumbled,” says Stephen Engelberg. Many people felt it was in a strong position compared with other regional papers — if nothing else because the region is so wealthy and influential. “I don’t think they figured out how to be indispensable in California,” notes a top editor. “I think that they tried to be a smaller New York Times, but there already is the New York Times,” says another top editor.

“Ownership is important. Never underestimate that, as they say. It’s a cliché, but it starts at the top,” says a veteran newspaperman. In 2018, Patrick Soon-Shiong, a biotech billionaire, bought it. “I think what happened there was a well-meaning but way-in-over-his-head owner who was basically extorted to rescue a beautiful but nearly doomed hostage for $500 million or whatever,” says an editor-in-chief. Then he put more money into it but didn’t fix the problems. “It’s gone wrong over too many years. The unionization has made everything more expensive. Print is dying, yet the staff is so not digitally focused enough,” they say. “The staff really didn’t have the skill sets necessary to achieve a turnaround. And the New York Times, by the way, in 2008, didn’t have those skill sets either, but it managed people out who refused to change it, bought out a whole bunch of older people, hired a whole bunch of new people, and then did not lay them off as the L.A. Times did.”

In 2021, Soon-Shiong hired Kevin Merida as editor, but he left early this year; it has been reported that the two clashed. Others in the newsroom have complained about the owner’s very progressive daughter taking too close an interest in the paper’s coverage. (The paper has since cut 20 percent of its newsroom.)

Another thing it never did: As the Hollywood trades went digital (with Jay Penske buying up Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, and Deadline) and The Ankler and Puck competed for the insider, the L.A. Times didn’t become a player in that — its home market. “Everything about them is so ideological, flat,” says a media executive. “I remember ‘Are Freeways Racist?’ as a perfect example of an L.A. Times story.”

So what is to be done? “My hope is that the L.A. Times fights its way out and follows more of the path of the Boston Globe,” a regional paper that has a solid digital subscription business, says another media executive. “But there’s kind of a cycle where you lose your best writers, you lose your best people, then you start to do things to try to make your model work, and then you’re in a real problem.”

The Trump Bump Gave the Washington Post a Bunch of New Subscribers — Then They Blew It.

It wasn’t so long ago that the Washington Post was on a roll with Jeff Bezos’s checkbook backing up Marty Baron’s editorial leadership. Bezos bought the Post in 2013 for $250 million after the paper’s lack of digital strategy — both Vox and Politico were founded by Post refugees — put its future in peril. He invested deeply to expand the newsroom. At the height of the so-called Trump Bump, under its “Democracy Dies in Darkness” slogan, digital subscriptions surged. But some argue the chaotic newsmaking presidency of Donald Trump masked a host of shortsighted business decisions. “The Post and the Times had a huge run-up during the Trump administration, and the Times used that time to diversify into games and health and lifestyle items, cooking, and the Post just acted as though this moment would last forever,” says a magazine editor. But after that, unlike the Times, the Post didn’t have a plan for what to invest in next that wasn’t politics, and after Baron left and was replaced by Sally Buzbee — then-publisher Fred Ryan’s pick — even that coverage seemed to lose its edge.

“They hadn’t built a sustainable editorial model that could support itself, post-resistance Trump era. And they hired some of the wrong people,” says another media executive. Meanwhile, the Post missed out on the arrival of a new era of political and policy coverage, allowing competitors to crib its audience.

“The Washington Post is screwed. They screwed themselves, maybe eternally,” says a digital-media executive. “Gross mismanagement, lack of a strategy, crappy culture, complex unions, allowing too many people from Politico to Axios to the New York Times to own categories they once had a chance to own.” As Bari Weiss says, “They should dominate D.C. They should get every scoop related to the federal government. And they just don’t.”

Even Bezos’s efforts to fix it of late have led to more tumult. This summer, it came out that his new publisher, Will Lewis, who arrived at the top of the year, had tried to shunt Buzbee into a new gig running a “third newsroom” focused on service and social-media journalism. But Buzbee quit, and Lewis’s hand-picked crony replacement for her, a Brit named Robert Winnett, was forced to step back after accusations of being too Fleet Street. Another onetime Lewis associate, Matt Murray, earlier replaced in the top Wall Street Journal job by Emma Tucker, was brought in to be interim editor. Now, many people think he’ll just end up staying on.

“I think what’s going on at the Post is a little concerning. This talk about a third newsroom, I don’t really understand it,” tsk-tsks a rival top editor. Others are less harsh. “I think the third-newsroom idea is great. Terrible branding, but it’s smart,” says a media executive. “The current commercial side of the Post is run by people who understand the subscription model. I think it’s much more clear now that they are focused,” says an editor. And as Ben Smith notes, “the Washington Post is still the Washington Post. Washington is still a place. Political news is still a thing. I think they’ll ultimately find their way to buying Punchbowl and trying to eat Politico’s lunch.”

What If Bezos Goes Shopping? The Lesson of Axios.

The rumor right now is that Will Lewis wants to get Jeff Bezos to open his wallet. That would be a throwback to 2021, when Axel Springer bought Politico for about $1 billion, and 2022, when the Times bought The Athletic for $550 million and Cox Enterprises dropped $525 million on Axios. The last two are viewed skeptically today. The Times continues to lose money on The Athletic, and, according to one media executive, “Cox way overpaid, and Axios doesn’t make any money.” (Earlier this year, Axios laid off about 10 percent of its workforce.) Not that Axios, which was founded by Politico and Post vets Jim VandeHei and Mike Allen (along with Roy Schwartz) in 2016 to create essentially a PowerPoint presentation of news (a.k.a. “Smart Brevity”), doesn’t have its defenders. “In moments of peak political excitement, Axios AM is still a version of the Times homepage to me,” says Jon Kelly. But as Janice Min notes, “Not to be dire, but it feels like Axios and The Athletic are going to go down as the two luckiest places that got hundreds of millions while you still could.”

Semafor Bets It Can Still Sell Enough Ads to Support Itself.

If it can only reach a truly elite audience and get enough of them to come to live events.

Semafor, founded by Ben Smith and Justin Smith in 2022, fancies itself a global news organization with a small team of journalists based in the U.S., Africa, and, most recently, the Gulf. “What I’m seeing is a curated, cost-effective, focused approach to thinking about how to share and talk about content,” says Matt Murray, “and a careful approach to growth. And it’s telling me something about how news is evolving.” Semafor launched having raised $25 million from various rich people, and because of the prominence of the Smiths in the business, many people signed up for its newsletters. Semafor’s scoops, when they come, often have resonance. But it’s still scrappy. Events — curated live journalism gatherings featuring heavy hitters across politics, business, and tech — turned out to be half of their business. Semafor claimed to have achieved several months of profitability in its first full year, with 50 percent of revenue coming from events, and last year made more than $10 million in revenue, split between advertising and events. Semafor also struck a deal with Microsoft, which is sponsoring an AI “breaking-news feed.” Early reports said the Smiths had planned to evolve into a paywall model, but they haven’t done so yet; instead, they are grabbing revenue where they can.

There Has to Be a Way for Local News to Survive.

“We have to be careful about not using the ‘in peril’ narrative too much, where people will think it’s already all dead and there’s nothing left to save,” says CJR’s Sewell Chan, who spent three years running the nonprofit Texas Tribune. Chan points to two bright spots in efforts to support local news: the National Trust for Local News, which acquires vulnerable community papers and invests in their development, and the American Journalism Project, which tries to rebuild local news by seeding local digital start-ups.

Audience interest in local stories is high, Apple News has found. “That’s part of what we’re trying to do — connect local news outlets with their audiences again,” says Lauren Kern of Apple News. “After the Apalachee school shooting earlier this fall, we relied on the Atlanta Journal-Constitution for coverage,” she notes. “The North Dakota state abortion ban was ruled unconstitutional, and we have the North Dakota Monitor to literally put at the top of a national news app.”

Among other experiments are small, sometimes worker-owned or nonprofit newsrooms around the country. San Francisco has 27 news organizations — about the same as it had a decade ago, thanks to a mix of nonprofits, radio stations, and, yes, the largesse of various rich people, of which the city has no shortage. In New York, there’s the swashbuckling Hell Gate and the more self-serious nonprofit The City. But there’s also the Murdoch-owned New York Post, which has survived by becoming, as its editor Keith Poole puts it, “a national digital brand.” That means it peddles national news, tabloid sensationalism, gossip, and Fox News–adjacent talking points that make it sometimes seem to despise the very city it’s based in. “We have to treat our news very differently locally and nationally. Not all readers will necessarily be interested in education policy in New York City,” Poole says. “We’re profitable — little-known fact. We’ve been profitable for the last three years in a row.”

The biggest threat to local news is hedge funds like Alden Global Capital that have gobbled up and then gutted regional papers across the country. “These are either zombie newspapers or soon-to-be-zombie newspapers. I don’t know if they’re going to make it,” says Stephen Engelberg.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, though, is owned by Cox Enterprises, a family-owned company that gave the paper a multiyear building plan. “There’s a difference between managing decline and investing in transformation,” says editor Leroy Chapman Jr. But, by and large, “the business model for local news is broken. It really is,” he adds. “There has to be, among the public and among elected officials, a recognition of how vital local news is to thriving communities” and “public investment” in protecting it. “We need some help to have a business model that lets us recoup fairly what we should, based upon what we produce, and that will provide the sort of thing our democracy needs, which is objective fact.”

A Brief Concerned Note About Air Mail.

“It’s like a digital version of a classic magazine. So that’s really a different kind of delivery. I think they can be a really valuable contribution to the voice, and I think they can be interesting. But I think (1) the economics are still tough, (2) the audience growth may be limited, and (3) it’s a lot of work to keep them interesting and hustle your audience and keep them engaged and keep them going.” — An editor-in-chief

What’s the Point of Print?

“Beats the shit out of me.” — Jim VandeHei

“Oh, you’re funny. Any media operator who looks at the unit economics of print will have a hard time answering that question.” — Jon Kelly

But Actually …

It’s not completely obsolete and has become a way for publications to attract and retain subscribers and lure in both celebrities and high-end writers who still care about appearing in print (just the other week, The Atlantic announced it was upping its frequency from ten to 12 print issues a year). And magazines are still riding the pandemic luxury-fashion boom; those fashion advertisers are hungry for glossy pages to appear in.

“Print is a luxury item.” — Mel Ottenberg, editor-in-chief, Interview magazine

“I’m trying to think of what to say instead of ‘a business card,’ but it really is like a business card. It’s a manifesto for what your brand stands for.” — Willa Bennett

“We obviously care deeply about print, but in terms of growth, it’s not where our focus is.” — Emma Tucker

“Keanu Reeves, Frank Ocean, Rob Pattinson, Beyoncé — they are not coming to a GQ Instagram shoot.” — Will Welch, global editorial director, GQ and Pitchfork

Covers, in Particular, Are Still Important …

Magazines Still Need Celebrity Covers …

“It’s an incredible point of access, and it gives us the opportunity to create an iconic image with a point and a purpose and a message that then permeates all our other platforms. Chappell Roan was shot by Inez & Vinoodh, and she’s at this incredible moment in her rise in her career, and it’s a deep interview and the writer spent days with her, and without print, that wouldn’t have happened. And then there’s video and all these other assets. Print is the tip of the spear, but the majority of it is digital. The impact of it, the symbolism of it, opens a door for us. That’s really, really critical.” — Gus Wenner