Abstract 抽象

In the context of (digital) human–machine interaction, people are increasingly dealing with artificial intelligence in everyday life. Through this, we observe humans who embrace technological advances with a positive attitude. Others, however, are particularly sceptical and claim to foresee substantial problems arising from such uses of technology. The aim of the present study was to introduce a short measure to assess the Attitude Towards Artificial Intelligence (ATAI scale) in the German, Chinese, and English languages. Participants from Germany (N = 461; 345 females), China (N = 413; 145 females), and the UK (N = 84; 65 females) completed the ATAI scale, for which the factorial structure was tested and compared between the samples. Participants from Germany and China were additionally asked about their willingness to interact with/use self-driving cars, Siri, Alexa, the social robot Pepper, and the humanoid robot Erica, which are representatives of popular artificial intelligence products. The results showed that the five-item ATAI scale comprises two negatively associated factors assessing (1) acceptance and (2) fear of artificial intelligence. The factor structure was found to be similar across the German, Chinese, and UK samples. Additionally, the ATAI scale was validated, as the items on the willingness to use specific artificial intelligence products were positively associated with the ATAI Acceptance scale and negatively with the ATAI Fear scale, in both the German and Chinese samples. In conclusion we introduce a short, reliable, and valid measure on the attitude towards artificial intelligence in German, Chinese, and English language.

在(数字)人机交互的背景下,人们越来越多地在日常生活中与人工智能打交道。通过这种方式,我们观察到以积极的态度拥抱技术进步的人类。然而,其他人则特别持怀疑态度,并声称预见到这种技术使用会带来重大问题。本研究的目的是引入一个简短的措施来评估德语、中文和英语对人工智能的态度(ATAI 量表)。来自德国 (N = 461;345 名女性)、中国 (N = 413;145 名女性) 和英国 (N = 84;65 名女性) 的参与者完成了 ATAI 量表,为此测试了析因结构并在样本之间进行了比较。来自德国和中国的参与者还被问及他们是否愿意与自动驾驶汽车、Siri、Alexa、社交机器人 Pepper 和人形机器人 Erica 互动/使用,这些都是流行的人工智能产品的代表。结果显示,五项 ATAI 量表包括两个负相关因素,评估 (1) 接受和 (2) 对人工智能的恐惧。发现德国、中国和英国样本的因子结构相似。此外,ATAI 量表也得到了验证,因为在德国和中国样本中,使用特定人工智能产品意愿的项目与 ATAI 接受量表呈正相关,与 ATAI 恐惧量表呈负相关。总之,我们介绍了一个简短、可靠且有效的衡量标准,以德语、中文和英语对人工智能的态度。

Similar content being viewed by others

其他人正在查看的类似内容

Explore related subjects 探索相关主题

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.发现来自相关学科顶级研究人员的最新文章、新闻和故事。

使用我们的提交前清单

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

避免稿件上的常见错误。

1 Introduction 1 介绍

Recent years have seen tremendous developments in products of technologies within artificial intelligence (AI). While some people appear to be open towards the rise of AI products in everyday life and appreciate the advantages, others seem sceptical and concerned about the emerging impact of AI products. Introducing a short and valid measure to assess individual differences in such attitudes was the aim of the present study to enable future research on human–AI interaction.

近年来,人工智能 (AI) 领域的技术产品取得了巨大发展。虽然有些人似乎对 AI 产品在日常生活中的兴起持开放态度并欣赏其优势,但其他人似乎对 AI 产品的新影响持怀疑和担忧态度。引入一种简短而有效的措施来评估这种态度的个体差异是本研究的目的,以便将来对人与人工智能互动的研究成为可能。

The term AI refers to a technology where software and/or machines are able to mimic (certain aspects of) human intelligence (for a more elaborate discussion see Fetzer [1]). As such, AI is a broad discipline encompassing a wide range of scientific disciplines such as computer science, engineering, biology, neuroscience, and psychology. During the last years, products in the field of AI are, undoubtedly, getting “smarter” in terms of the machine learning algorithms used. Recent examples are Google’s AlphaGo (an AI computer program that plays the game “Go”) defeat over a Chinese Go Master [2] or Google’s AutoML (Automatic Machine Learning; invented to teach AI software to build other AIs) creating an AI, which is smarter than the previous man-made one [3]. In line with this progress, recent years have seen dramatic developments in the construction of self-driving cars, a forthcoming billion-dollar industry. Here, AI will support humans, which will no longer need to pay attention to the roads while travelling. An example for such an ongoing project is the self-driving car of Google [4]. Further to this, several products relying on AI have already been launched for use in everyday life with considerable media attention in the past few years. Prominent examples are Siri developed by Apple, currently included in Apple devices, such as computers and smartphones (https://www.apple.com/siri/), and Alexa developed by Amazon (https://developer.amazon.com/alexa) [5]. Siri represents a digital service humans can give voice commands to in order to access information, such as the weather forecast and information on directions to navigate to a specified destination. Comparably, Amazon launched a service called Alexa, an AI product that — like Siri — reacts to human voice commands. One can instruct Alexa to play a song, or to add items to a shopping list, to name a few examples. Similarly, Google relies on AI for its voice assistants, as used in Google Home (Smart Home Assistant) and installed in current Android Smartphones (https://assistant.google.com/intl/en_uk/). Furthermore, AI research has led to the development of robots, including humanoid robots [6], which have the ability to be companions to humans and are, therefore, deemed as social robots. Pepper, for example, is a robot already used within over 2,000 companies around the world to interact with visitors and customers. It was developed by the company Aldebaran and is able to recognize faces and partake in conversations with humans (https://www.softbankrobotics.com/emea/en/pepper). Further examples for AI-based humanoid robots are those created by Hiroshi Ishiguro and his colleagues. Among others, the team built a humanoid female robot named Erica, which actually looks human-like and is declared “an autonomous conversational android with an unprecedented level of human-likeness and expressivity, as well as advanced multimodal sensing capabilities” [7], p 22. Another example would be Atlas®, which was created by Boston Dynamics [8]. It is described as “the most dynamic humanoid robot” [8] and its aim is to be deployed for rescue work in situations, which humans would not survive [8, 9].

人工智能一词是指软件和/或机器能够模仿人类智能(某些方面)的技术(更详细的讨论参见 Fetzer [1])。因此,AI 是一门广泛的学科,涵盖了计算机科学、工程、生物学、神经科学和心理学等广泛的科学学科。在过去几年中,AI 领域的产品无疑在使用的机器学习算法方面变得越来越“智能”。最近的例子是谷歌的 AlphaGo(一种玩“围棋”游戏的人工智能计算机程序)击败了中国围棋大师 [2],或者谷歌的 AutoML(自动机器学习;发明来教人工智能软件构建其他人工智能)创造了一个比以前的人造人工智能更聪明的人工智能 [3]。随着这一进步,近年来,自动驾驶汽车的制造取得了巨大发展,这是一个即将到来的价值数十亿美元的产业。在这里,人工智能将支持人类,人类在旅行时不再需要关注道路。这样一个正在进行的项目的一个例子是 Google 的自动驾驶汽车 [4]。此外,在过去几年中,一些依赖人工智能的产品已经推出用于日常生活,并受到媒体的广泛关注。突出的例子是 Apple 开发的 Siri,目前包含在 Apple 设备中,例如计算机和智能手机 (https://www.apple.com/siri/),以及 Amazon 开发的 Alexa (https://developer.amazon.com/alexa) [5]。Siri 代表一种数字服务,人类可以向其发出语音命令以访问信息,例如天气预报和导航到指定目的地的方向信息。 相比之下,亚马逊推出了一项名为 Alexa 的服务,这是一款与 Siri 一样对人类语音命令做出反应的 AI 产品。可以指示 Alexa 播放歌曲,或将商品添加到购物清单中,仅举几个例子。同样,谷歌的语音助手也依赖人工智能,就像在 Google Home(智能家居助手)中使用的那样,也安装在当前的 Android 智能手机 (https://assistant.google.com/intl/en_uk/) 中。此外,人工智能研究导致了机器人的发展,包括类人机器人 [6],它们能够成为人类的伴侣,因此被视为社交机器人。例如,Pepper 是一种机器人,已被全球 2,000 多家公司用于与访客和客户互动。它由 Aldebaran 公司开发,能够识别面孔并参与与人类的对话 (https://www.softbankrobotics.com/emea/en/pepper)。基于 AI 的人形机器人的更多例子是 Hiroshi Ishiguro 和他的同事创造的机器人。其中,该团队构建了一个名为 Erica 的人形女性机器人,它实际上看起来像人类,并被宣布为“一种自主对话机器人,具有前所未有的人类相似性和表现力水平,以及先进的多模态传感能力”[7],第 22 页。另一个例子是 Atlas®,它由 Boston Dynamics [8] 创建。它被描述为“最具活力的人形机器人”[8],其目标是在人类无法生存的情况下进行救援工作 [8, 9]。

The rise of AI in daily life bears several opportunities and future promises, including safer driving or improved medical care. For example, one is able to ask the AI assistants for help by voice command. This enables people to start a navigation system while already driving, making it unnecessary to stop the car to manually set it up, or even manually setting it up while driving. Also, AI is increasingly used in the medical sector. For instance, AI is used for robots to assist elderly patients or surgeons [10]. Also Pepper serves in hospitals in Belgium as a receptionist [11]. However, alongside such positive outcomes, naturally, the progress in AI research and AI development has several disadvantageous consequences and potential perils. As with every technological progress, machines are progressively being used to replace humans at work, which causes tremendous numbers of employment dismissals every year. In one study it was estimated that around 38% of the jobs, which are currently carried out by humans, will be cut due to automation in the USA by the year 2030 [12]. Needless to say, the “smarter” machines get (i.e., the more effective the AI gets), the more jobs can be carried out by these machines. In turn, these jobs will be taken from humans by the machines. However, some also argue that AI can create new job opportunities [13]. Moreover, concerns with respect to data privacy are increasingly debated with respect to the increasing engagement of AI products in daily life. Prominent examples are the big tech companies recording, listening to, and analysing private conversations of people via their AI products [14].

AI 在日常生活中的兴起带来了许多机会和未来前景,包括更安全的驾驶或更好的医疗保健。例如,可以通过语音命令向 AI 助手寻求帮助。这使人们可以在已经驾驶时启动导航系统,无需停下汽车进行手动设置,甚至无需在驾驶时手动设置。此外,人工智能越来越多地用于医疗领域。例如,人工智能被用于机器人协助老年患者或外科医生 [10]。此外,Pepper 还在比利时的医院担任接待员 [11]。然而,除了这些积极成果外,人工智能研究和人工智能开发的进展自然也带来了一些不利后果和潜在危险。与每一项技术进步一样,机器正逐渐被用来取代工作中的人类,这导致每年有大量的失业者。在一项研究中,估计到 2030 年,美国目前由人类从事的工作岗位中约有 38% 将因自动化而被削减 [12]。毋庸置疑,机器越“智能”(即 AI 越有效),这些机器可以执行的工作就越多。反过来,这些工作将被机器从人类手中夺走。然而,一些人也认为人工智能可以创造新的就业机会 [13]。此外,随着 AI 产品在日常生活中的参与度越来越高,人们对数据隐私的担忧也越来越受到争论。突出的例子是大型科技公司通过其 AI 产品记录、监听和分析人们的私人对话 [14]。

In line with the existing advantages, as well as the disadvantages, of AI products, it does not seem surprising that some people have a very open-minded opinion and accept the emergence of AI products and acknowledge their advantages for humans. In contrast to this, others seem to be ambivalent or even sceptical and fearful regarding the rise of AI products (LINK Institut (2018) as cited in Statista [15]). This leads as far as to prominent influencers in the field, such as Stephen Hawking and Elon Musk, publicly stating that progress in AI research has the potential to end humankind [16, 17].

根据人工智能产品的现有优点和缺点,有些人持非常开放的观点并接受人工智能产品的出现并承认它们对人类的优势也就不足为奇了。与此相反,其他人似乎对人工智能产品的兴起持矛盾态度,甚至持怀疑和恐惧态度(LINK Institut (2018),引自 Statista [15])。这导致该领域的杰出影响者,如斯蒂芬霍金和埃隆马斯克,公开表示人工智能研究的进展有可能终结人类 [16, 17]。

Given the varying attitudes towards AI, the main aim of this study is to develop and introduce a short, reliable, and valid measure to assess individual differences in the attitude towards AI. As AI is a worldwide phenomenon, it is important to present and test such a measure in various languages and across cultures. Therefore, German, Chinese, and English versions of the self-report measure will be subject to this study. The factorial structure of this measure, including invariance analyses across samples from Germany, China, and the UK, will be investigated. Moreover, potential gender differences in this measure will be examined. Thereby, it is tested whether the previously reported effects of more positive attitudes in males found with regard to technology acceptance, a field closely related to AI, extend to the current measure [18, 19]. Lastly, the associations of the newly developed measure with items on the willingness to use several specific AI products (self-driving cars, Siri, Alexa, Pepper, and Erica) in Germany and China will be investigated for validation. In detail, we expect a more positive attitude towards AI to be associated with a higher willingness to use such AI products. More negative attitudes should be associated with lower willingness to use such AI products.

鉴于对 AI 的态度各不相同,本研究的主要目的是开发和引入一种简短、可靠且有效的措施来评估对 AI 态度的个体差异。由于 AI 是一种世界性的现象,因此以各种语言和跨文化展示和测试这样的衡量标准非常重要。因此,自我报告措施的德语、中文和英语版本将受到本研究的约束。将研究该措施的因子结构,包括来自德国、中国和英国的样本的不变性分析。此外,将检查该措施中的潜在性别差异。因此,测试了先前报道的男性对技术接受度(与 AI 密切相关的领域)的更积极态度的影响是否延伸到当前的测量 [18, 19]。最后,将调查新开发的措施与德国和中国使用几种特定 AI 产品(自动驾驶汽车、Siri、Alexa、Pepper 和 Erica)的意愿项目的关联以进行验证。具体来说,我们预计对 AI 持更积极的态度与使用此类 AI 产品的意愿更高相关联。更多的消极态度应该与使用此类 AI 产品的意愿较低有关。

2 Materials and Methods

阿拉伯数字 材料和方法

2.1 Samples 2.1 样品

The initial dataset of the German sample included N = 465 participants. After exclusion of data of participants who took part in the study twice (N = 4 datasets), a final sample of N = 461 participants (N = 116 males, N = 345 females) remained. The sample was derived from the Ulm Gene Brain Behavior Project (Ulm University, Ulm, Germany) and, therefore, partly overlaps with samples of other studies reporting data derived from this project. These other studies, however, do not overlap thematically with the present study. The mean age of the present German sample was M = 22.31 years (SD = 5.06 years) with a median of 21 years. The majority of the participants were university students (N = 419; 91%).

德国样本的初始数据集包括 N = 465 名参与者。在排除两次参与研究的参与者的数据(N = 4 个数据集)后,仍保留 N = 461 名参与者(N = 116 名男性,N = 345 名女性)的最终样本。该样本来自 Ulm 基因脑行为项目(德国乌尔姆市乌尔姆大学),因此与报告该项目数据的其他研究样本部分重叠。然而,这些其他研究在主题上与本研究并不重叠。目前德国样本的平均年龄为 M = 22.31 岁 (SD = 5.06 岁),中位数为 21 岁。大多数参与者是大学生 (N = 419;91%)。

The initial Chinese dataset comprised N = 414 participants. One of the datasets of one participant who took part in the study twice (N = 1) was excluded. Therefore, the final sample consisted of N = 413 participants (N = 268 males, N = 145 females). Several participants of this sample (N = 284) were derived from the Chengdu Gene Brain Behavior Project (University of Electronic Science and Technology of China (UESTC), Chengdu, China) and, therefore, this sample partly overlaps with samples of other studies reporting data of this project. The remaining Chinese participants were recruited at Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Bejing, China. The mean age of the participants of the present Chinese sample was M = 21.19 years (SD = 2.41 years) with a median of 21 years. The majority of the participants were university students (N = 369; 89%).

最初的中文数据集包括 N = 414 名参与者。排除了一名参加两次研究 (N = 1) 的参与者的数据集之一。因此,最终样本由 N = 413 名参与者组成(N = 268 名男性,N = 145 名女性)。该样本的几名参与者 (N = 284) 来自成都基因脑行为项目(中国电子科技大学 (UESTC),中国成都),因此,该样本与报告该项目数据的其他研究样本部分重叠。其余的中国参与者是从中国北京的北京建筑大学招募的。目前中国样本的参与者的平均年龄为 M = 21.19 岁 (SD = 2.41 岁),中位数为 21 岁。大多数参与者是大学生 (N = 369; 89%)。

In order to investigate the English translation of the Attitude Towards Artificial Intelligence (ATAI) scale with regards to its psychometric properties, N = 84 participants (N = 19 males, N = 65 females, age: M = 25.21 years, SD = 7.71 years, median = 23 years), who were native English speakers, completed the English version of the ATAI scale (see section on Self-Report Measures). These participants were recruited in the UK at Goldsmiths, University of London, London, England. The majority of the participants were university students (N = 69; 82%).

为了调查对人工智能的态度 (ATAI) 量表的心理测量特性的英文翻译,N = 84 名参与者(N = 19 名男性,N = 65 名女性,年龄:M = 25.21 岁,SD = 7.71 岁,中位数 = 23 岁),他们是以英语为母语的人,完成了英文版的 ATAI 量表(参见自我报告测量部分)。这些参与者是在英国伦敦伦敦大学金史密斯学院招募的。大多数参与者是大学生 (N = 69; 82%)。

The data is available from the authors upon reasonable request (as we did not specifically ask participants for their consent to publish anonymized data, we cannot make the data freely available).

数据可在合理要求下从作者处获得(由于我们没有明确征求参与者同意发布匿名数据,因此我们无法免费提供数据)。

2.2 Procedure, Ethics, and Consent

2.2 元程序、道德和同意

The studies were conducted online in Germany, China, and the UK via the SurveyCoder tool (https://ckannen.com/). The local ethics committees at Ulm University, Ulm, Germany and the UESTC, Chengdu, China approved the present studies. There was no separate proposal submitted to Goldsmiths, University of London, London, England. All participants gave informed electronic consent prior to participation.

这些研究是通过 SurveyCoder 工具 (https://ckannen.com/) 在德国、中国和英国在线进行的。德国乌尔姆大学和中国成都 UESTC 的当地伦理委员会批准了本研究。没有向英国伦敦伦敦大学金史密斯学院提交单独的提案。所有参与者在参与前都给予了知情的电子同意书。

2.3 Self-Report Measures

2.3 自我报告措施

2.3.1 Item Generation

2.3.1 项目生成

Shortly before this research was conducted, a media debate was occurring in Germany focussing on the question on whether or not the rising impact of AI in daily life would result in a loss of jobs and/or would have some form of detrimental effects on humankind. In this debate, it became obvious that there are groups of people who do not openly embrace these technologies, while others use services, such as Alexa and Siri, very comfortably and without concern. The argument that AI will be the cause of many job losses was mentioned frequently in the context of reasons to fear AI. On the contrary, the opinion that people can live and work more effectively by using AI products was discussed in the context of acceptance of AI (see also representative study in Germany by Marsden [20]). Moreover, several AI products already in use in everyday life were discussed (e.g. Siri and Alexa). In brief, the key points of argument of this debate were the basis for the construction of the proposed scale assessing the attitude towards AI (ATAI scale) and additional items measuring the willingness to use specific AI products.

在进行这项研究之前不久,德国正在进行一场媒体辩论,重点是人工智能对日常生活的影响不断上升是否会导致失业和/或是否会对人类产生某种形式的不利影响。在这场辩论中,很明显,有一群人并不公开接受这些技术,而其他人则非常舒适且毫无顾虑地使用 Alexa 和 Siri 等服务。人工智能将成为许多失业原因的论点在恐惧人工智能的理由中经常被提及。相反,人们通过使用人工智能产品可以更有效地生活和工作的观点是在接受人工智能的背景下讨论的(另见 Marsden [20] 在德国的代表性研究)。此外,还讨论了日常生活中已经使用的几种人工智能产品(例如 Siri 和 Alexa)。简而言之,这场辩论的关键论点是构建评估对人工智能态度的拟议量表(ATAI 量表)的基础,以及衡量使用特定人工智能产品意愿的附加项目。

The items of the ATAI scale and the items about specific AI products were developed in German language, translated into Chinese and English, and then back translated into German independently by two bilingual researchers (forward and backward translations). Following this, the German original and the back translations were carefully checked for compatibility and the translations were adjusted if necessary. Additionally, native speakers checked the translations for linguistic and grammatical correctness.

ATAI 量表的项目和有关特定 AI 产品的项目以德语开发,翻译成中文和英文,然后由两名双语研究人员独立翻译成德语(正向和反向翻译)。在此之后,仔细检查了德文原译和反向翻译的兼容性,并在必要时调整了翻译。此外,母语人士会检查翻译的语言和语法正确性。

2.3.2 Attitude Towards Artificial Intelligence Scale

2.3.2 对人工智能的态度量表

The ATAI scale consists of five items. The German, Chinese, and English versions of the questionnaire are presented in Table 1. An 11-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “strongly disagree” to 10 = “strongly agree” was used as response scale. An 11-point Likert scale was used to get a fine-grained picture with respect to a person’s attitude towards AI, in particular as a short measure was constructed, here. Explicitly, it is mentioned that future research endeavors should check if other forms of Likert scaling are more appropriate in the context of the present scale.

ATAI 量表由五个项目组成。问卷的德文、中文和英文版本如表 1 所示。使用从 0 =“非常不同意”到 10 =“非常同意”的 11 点李克特量表作为响应量表。使用 11 点李克特量表来获得关于一个人对 AI 态度的精细图片,特别是在这里构建了一个简短的测量。明确地提到,未来的研究工作应该检查其他形式的李克特量表是否更适合当前的量表。

表 1 德语、中文和英语的 ATAI 量表项目

2.3.3 Trust in and Usage of Several Specific AI Products

2.3.3 信任和使用几种特定的 AI 产品

Participants from Germany and China were additionally introduced to five AI products by means of a picture and accompanying descriptive sentences. These AI products were self-driving cars, Siri, Alexa, Pepper, and Erica. After the introduction to each product participants were asked to rate their trust in each product as well as their willingness to use/interact with the product on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “strongly disagree” to 10 = “strongly agree”. Lastly, participants answered with “yes”/“no” when questioned if they actually use/interact or have used / interacted with each of the specific AI products.

来自德国和中国的参与者还通过图片和随附的描述性句子了解了五款 AI 产品。这些 AI 产品是自动驾驶汽车、Siri、Alexa、Pepper 和 Erica。在介绍每个产品之后,参与者被要求以 11 分制的李克特量表对他们对每个产品的信任度以及他们使用产品/与产品互动的意愿进行评分,范围从 0 =“非常不同意”到 10 =“非常同意”。最后,当被问及他们是否实际使用/交互或已经使用/交互每个特定的 AI 产品时,参与者回答“是”/“否”。

Please note that in the initial online survey (which is presented in the main manuscript) the items on AI products were presented before the ATAI scale. Also, a short introduction about AI in daily life was presented alongside these items. In order to exclude the possibility of the introduction influencing the results regarding the ATAI scale and its associations with the AI product items (e.g. the willingness to use them), we conducted a control survey with N = 82 participants from China. In the control survey, neither an introduction on AI, nor any information about the fact that the products were AI products was given. The results of the sample of the control survey are presented in the Supplementary Material. As the results are similar to the results presented in the main manuscript, we conclude that the introduction did not bias participants’ response style.

请注意,在最初的在线调查(在主要手稿中介绍)中,关于 AI 产品的项目是在 ATAI 量表之前提出的。此外,与这些项目一起还介绍了日常生活中人工智能的简短介绍。为了排除引入影响 ATAI 量表结果及其与 AI 产品项目的关联(例如使用它们的意愿)的可能性,我们对来自中国的 N = 82 名参与者进行了一项对照调查。在对照调查中,既没有提供 AI 的介绍,也没有提供任何关于产品是 AI 产品的信息。对照调查的样本结果在补充材料中介绍。由于结果与主要手稿中呈现的结果相似,我们得出结论,引言没有使参与者的回答风格产生偏差。

2.4 Statistical Analyses

2.4 统计分析

All analyses were implemented using the statistical software R version 3.5.2 [21], R-Studio version 1.1.463 [22], and several R-packages such as car [23], dplyr [24], effsize [25], gmodels [26], GPArotation [27], Hmisc [28], lavaan [29], ppcor [30], psych [31], and semTools [32].

所有分析均使用统计软件 R 版本 3.5.2 [21]、R-Studio 版本 1.1.463 [22] 和几个 R 包进行,例如 car [23]、dplyr [24]、effsize [25]、gmodels [26]、GPArotation [27]、Hmisc [28]、lavaan [29]、ppcor [30]、psych [31] 和 semTools [32]。

First, the factorial structure of the ATAI scale was investigated by means of principal component analyses (PCAs) indicating a two-component structure in each of the three samples. The two components were rotated using the oblimin rotation to allow for correlations between the components. The two-factorial model based on the PCAs was tested by means of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs), followed by testing internal consistencies (by means of Cronbach’s α) of the two ATAI scales in each sample. Also, measurement invariance of the two-factorial model was tested across the three samples.

首先,通过主成分分析 (PCA) 研究 ATAI 量表的因子结构,表明三个样本中的每一个样本都具有双成分结构。使用 oblimin 旋转旋转两个组件,以允许组件之间的相关性。基于 PCA 的双因素模型通过验证性因子分析 (CFA) 进行测试,然后测试每个样本中两个 ATAI 量表的内部一致性 (通过 Cronbach α)。此外,在三个样本中测试了双因素模型的测量不变性。

The two ATAI scales derived from the PCAs showed a skewness and kurtosis of less than ± 1 in nearly all (sub-)samples (split by country/country and gender) from Germany, China, and the UK. Only in the Chinese male subsample the kurtosis of the ATAI Acceptance scale was 1.31. Therefore, a normal distribution was assumed for the two scales [33] given the negligible deviation in the Chinese male sample, only.

来自 PCA 的两个 ATAI 量表在来自德国、中国和英国的几乎所有(子)样本(按国家/国家和性别划分)中都显示偏度和峰度小于 ± 1。仅在中国男性子样本中,ATAI 接受量表的峰度为 1.31。因此,假设两个量表 [33] 呈正态分布,仅考虑到中国男性样本的可忽略不计的偏差。

Accordingly, correlations of the ATAI scales with age were calculated by means of Pearson correlations to check whether age should be treated as a control variable in further analyses. Differences between males and females, countries, and the gender by country interaction effect on the two ATAI scales were investigated using a multivariate multifactorial ANCOVA with age as control variable (see Sect. 3) and subsequent multifactorial ANCOVAs.

因此,通过 Pearson 相关性计算 ATAI 量表与年龄的相关性,以检查是否应在进一步分析中将年龄视为控制变量。使用以年龄为控制变量的多变量多因素 ANCOVA 研究了两个 ATAI 量表上男性和女性、国家之间的差异以及性别与国家之间的交互作用(见 Sect.3) 和随后的多因素 ANCOVAs。

To validate the ATAI scale, correlations between the scores in the two ATAI scales and the items on the willingness to use specific AI products were calculated in the German and Chinese samples. As some of the items assessing the willingness to use specific AI products did show a marked deviation from the normal distribution in accordance with the criteria by Miles and Shevlin [33] in at least one of the (sub-)samples, we opted for partial Spearman correlations with age included as covariate (see Sect. 3). These correlations were also calculated separately for males and females in the German and Chinese samples.

为了验证 ATAI 量表,在德国和中国样本中计算了两个 ATAI 量表的分数与使用特定 AI 产品意愿的项目之间的相关性。由于根据 Miles 和 Shevlin [33] 的标准,一些评估使用特定 AI 产品意愿的项目确实在至少一个(子)样本中显示出与正态分布的明显偏差,因此我们选择了将年龄作为协变量的部分 Spearman 相关性(参见 Sect.3). 德国和中国样本中男性和女性的这些相关性也分别计算。

Please note that there is an overlap in the wording between the second item of the ATAI scale (“I trust …”) and the items on trust in the AI products. Therefore, we only report correlations between the ATAI scale and the items on the willingness to use the specific AI products. The simultaneous use of the word “trust” could potentially lead to higher correlations and, therefore, an overestimation of the underlying correlations.

请注意,ATAI 量表的第二项(“我信任......”)与人工智能产品中的信任项目之间的措辞存在重叠。因此,我们只报告 ATAI 量表与使用特定 AI 产品意愿的项目之间的相关性。同时使用“信任”一词可能会导致更高的相关性,因此会高估潜在的相关性。

Lastly, all analyses were also calculated based on a sample excluding all univariate outliers in the ATAI scales (N = 1 in the German sample, N = 11 in the Chinese sample, N = 0 in the sample from the UK), classified by the formula defined by Tukey [34]. The results did not differ meaningfully depending on whether outliers were in- or excluded. Therefore, we decided to present results including all participants, including those who were classified as univariate outliers.

最后,所有分析也是基于一个样本计算的,该样本排除了ATAI量表中的所有单变量异常值(德国样本中N = 1,中国样本中N = 11,英国样本中N = 0),并按Tukey [34]定义的公式分类。结果没有有意义的差异,具体取决于异常值是被排除的。因此,我们决定呈现包括所有参与者的结果,包括那些被归类为单变量异常值的参与者。

3 Results 3 结果

3.1 Principal Component Analyses of the ATAI Items

3.1 ATAI 项目的主成分分析

The PCAs revealed two eigenvalues greater than 1 in each sample (Germany: 2.26, 1.06; China: 2.38, 1.20; UK: 2.31, 1.11), allowing for the extraction of two components. The item loadings on the oblimin rotated components reflected the wording of the items. Specifically, items reflecting positive attitudes towards AI (items 02, 04) loaded positively on one component (more specifically, on the second component with smaller eigenvalues), while loading from weakly positively to negatively on the other component (more specifically, the first component with higher eigenvalues). Items that represent negative opinions towards AI (items 01, 03, 05) showed the opposite pattern.

PCA 显示每个样本中有两个大于 1 的特征值(德国:2.26、1.06;中国: 2.38, 1.20;英国:2.31、1.11),允许提取两个组分。oblimin 旋转组件上的项目加载反映了项目的措辞。具体来说,反映对 AI 持积极态度的项目(项目 02、04)在一个组件上加载为正(更具体地说,在特征值较小的第二个组件上),而在另一个组件上从弱正加载到负加载(更具体地说,具有较高特征值的第一个组件)。代表对 AI 的负面看法的项目(项目 01、03、05)显示出相反的模式。

3.2 Confirmatory Factor Analyses, Reliabilities, and Measurement Invariance of the ATAI Scale

3.2 ATAI 量表的验证因子分析、可靠性和测量不变性

The two components extracted in the PCAs were labelled Acceptance (items 02, 04) and Fear (items 01, 03, 05). CFAs revealed negative associations between the two factors and, for the most part, an acceptable model fit for the two-factorial structure in all three samples (Germany: CFI: 0.976, TLI: 0.940, RMSEA: 0.075, SRMR: 0.032; China: CFI: 0.870, TLI: 0.676, RMSEA: 0.202, SRMR: 0.079; UK: CFI: 0.933, TLI: 0.833, RMSEA: 0.127, SRMR: 0.059) [35]. The standardized loadings of the items on the two factors are presented in Table 2. However, several fit indices indicated a non-satisfactory model-fit for the Chinese sample. This was most likely due to the fifth item weakly loading (0.23) on the Fear factor in the Chinese sample. A decision was made to keep the item for further analyses given the acceptable model fit for the samples from Germany and the UK. This topic is discussed in more detail in the discussion section of the present work.

在 PCA 中提取的两个组成部分被标记为 Acceptance(第 02、04 项)和 Fear(第 01、03、05 项)。CFA 揭示了两个因素之间的负相关,并且在大多数情况下,所有三个样本中双因素结构的可接受模型拟合(德国:CFI:0.976,TLI:0.940,RMSEA:0.075,SRMR:0.032;中国:CFI:0.870,TLI:0.676,RMSEA:0.202,SRMR:0.079;英国:CFI:0.933,TLI:0.833,RMSEA:0.127,SRMR:0.059)[35]。表 2 列出了项目对这两个因子的标准化载荷。然而,几个拟合指数表明中国样本的模型拟合不令人满意。这很可能是由于中国样本中的第五项对恐惧因子的弱加载 (0.23)。鉴于德国和英国样本的可接受模型拟合,我们决定保留该项目以供进一步分析。本主题在本书的讨论部分有更详细的讨论。

表 2 根据 CFA 对德国、中国和英国样本中 ATAI 量表项目对两个因素的标准化加载

The internal consistencies of the Acceptance and Fear scales were α = 0.65 and α = 0.66 in the German sample, α = 0.73 and α = 0.61 in the Chinese sample, and α = 0.64 and α = 0.65 in the sample from the UK. We deemed these values as acceptable given the low number of items per scale.

德国样本的接受和恐惧量表的内部一致性分别为 α = 0.65 和 α = 0.66,中国样本的 α = 0.73 和 α = 0.61,英国样本的 α = 0.64 和 α = 0.65。鉴于每个量表的项目数量较少,我们认为这些值是可以接受的。

Tests on measurement invariance revealed that configural invariance (see model fit) and equal loadings can be assumed across the three samples (delta Χ2 = 7.77, p = 0.255).

测量不变性测试表明,三个样本可以假设配置不变性(参见模型拟合)和相等的载荷 (delta Χ2 = 7.77,p = 0.255)。

3.3 Descriptive Statistics, Correlations with Age, and Country and Gender Differences

3.3 描述性统计、与年龄的相关性以及国家和性别差异

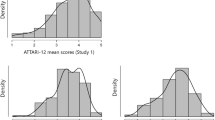

Descriptive statistics of the ATAI Acceptance and Fear scales derived from the PCAs are presented in Table 3 for each sample separately. Descriptive statistics of the items on the willingness to use the specific AI products are presented in the Supplementary Material alongside descriptive statistics on the items on whether participants actually use(d)/interact(ed) with specific AI products.

表 3 中分别列出了每个样本的 PCA 得出的 ATAI 接受量表和恐惧量表的描述性统计数据。补充材料中提供了有关使用特定 AI 产品的意愿项目的描述性统计数据,以及有关参与者是否实际使用特定 AI 产品/与特定 AI 产品交互的项目的描述性统计数据。

表 3 德国、中国和英国样本中两个 ATAI 量表的平均值和标准差(括号内)

Age did not correlate significantly with any of the two ATAI scales in the German sample, but with the Acceptance scale in the Chinese sample (r = 0.12, p = 0.019), and with the Fear scale in the sample from the UK (r = − 0.31, p = 0.005). When using Spearman correlations (age was not normally distributed in all samples), some more correlations turned out to be significant.

年龄与德国样本中的两个 ATAI 量表中的任何一个都没有显著相关性,但与中国样本中的接受量表 (r = 0.12, p = 0.019) 和英国样本中的恐惧量表 (r = − 0.31, p = 0.005) 相关。当使用 Spearman 相关性 (年龄并非呈正态分布于所有样本中) 时,更多的相关性被证明是显著的。

A multivariate multifactorial ANCOVA on differences in the two ATAI scales revealed significant effects of gender (F(2,950) = 9.22, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.019), country (F(4,1902) = 37.80, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.074), and the gender by country interaction (F(4,1902) = 3.26, p = 0.011, ηp2 = 0.007), but not of age (F(2,950) = 1.63, p = 0.073, ηp2 = 0.006). Further multifactorial ANCOVAs revealed that males scored higher than females in the ATAI Acceptance scale (F(1,951) = 18.33, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.019). No significant gender effect was observed on the ATAI Fear scale (F(1,951) = 3.36, p = 0.067, ηp2 = 0.004). Moreover, the samples from the three countries differed significantly in both ATAI scales (Acceptance: F(2,951) = 72.82, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.133; Fear: F(2,951) = 6.27, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.013) with the Chinese sample showing highest scores in the Acceptance scale and lowest scores in the Fear scale compared to the samples from Germany and the UK. It should be noted, though, that no scalar measurement invariance was found across the samples from the different countries. Therefore, an elaborate discussion on the interpretation of the differences between countries can be found in the discussion section. The gender by country interaction was significant on both scales (Acceptance: F(2,951) = 5.46, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.011; Fear: F(2,951) = 3.10, p = 0.046, ηp2 = 0.006). In the samples from Germany and the UK, males scored markedly higher on the Acceptance and lower on the Fear scale compared to females. In the Chinese sample, a trend in the same direction was visible, but to a smaller extent. Please note that the explanations on the effects of country and the gender by country interaction term rely on the descriptive statistics presented in Table 3.

对两个 ATAI 量表差异的多变量多因素 ANCOVA 揭示了性别 (F(2,950) = 9.22,p < 0.001,ηp2 = 0.019)、国家 (F(4,1902) = 37.80,p < 0.001,ηp2 = 0.074) 和性别与国家互动 (F(4,1902) = 3.26,p = 0.011,ηp2 = 0.007),但年龄 (F(2,950) = 1.63, p = 0.073,ηp2 = 0.006)。进一步的多因素 ANCOVA 显示,男性在 ATAI 接受量表中的得分高于女性 (F(1,951) = 18.33,p < 0.001,ηp2 = 0.019)。在 ATAI 恐惧量表上未观察到显着的性别影响 (F(1,951) = 3.36,p = 0.067,ηp2 = 0.004)。此外,来自三个国家的样本在两种 ATAI 量表上存在显着差异(接受度:F(2,951) = 72.82,p < 0.001,ηp2 = 0.133;恐惧:F(2,951) = 6.27,p = 0.002,ηp2 = 0.013),与德国和英国的样本相比,中国样本在接受量表中得分最高,在恐惧量表中得分最低。不过,应该注意的是,在不同国家的样本中没有发现标量测量不变性。因此,关于解释国家间差异的详细讨论可以在讨论部分找到。按国家划分的性别互动在两个量表上均显著(接受度:F(2,951) = 5.46,p = 0.004,ηp2 = 0.011;恐惧:F(2,951) = 3.10,p = 0.046,ηp2 = 0.006)。在德国和英国的样本中,与女性相比,男性在接受度方面的得分明显较高,而在恐惧量表上的得分明显较低。 在中国样本中,可以看到相同方向的趋势,但程度较小。请注意,对国家影响和按国家性别划分的交互作用术语的解释依赖于表 3 中提供的描述性统计数据。

3.4 Correlations Between the two ATAI Scales and the Items on the Willingness to Use Specific AI Products

3,4 两个 ATAI 量表与使用特定 AI 产品意愿项目的相关性

Partial Spearman correlations (controlled for age) between the ATAI Acceptance and Fear scales and the items on the willingness to use specific AI products for the German and Chinese samples are presented in Table 4.

表 4 列出了 ATAI 接受和恐惧量表之间的部分 Spearman 相关性(按年龄控制)以及德国和中国样本使用特定 AI 产品的意愿项目。

表 4 两种 ATAI 量表之间的部分 Spearman 相关性以及德国和中国样本中使用特定 AI 产品意愿的项目

As can be seen in Table 4, the ATAI Acceptance scale correlated substantially with all items on the willingness to use specific AI products in both samples from Germany and China. These correlations were all positive. In contrast, the ATAI Fear scale correlated negatively with these items in both samples from Germany and China. The observed associations were weaker compared to the correlations between the ATAI Acceptance scale and the items on the willingness to use the specific AI products.

从表 4 中可以看出,ATAI 接受量表与德国和中国样本中使用特定 AI 产品的意愿的所有项目都非常相关。这些相关性都是正的。相比之下,ATAI 恐惧量表与来自德国和中国的样本中的这些项目呈负相关。与 ATAI 接受量表与使用特定 AI 产品意愿的项目之间的相关性相比,观察到的关联较弱。

It is important to note that none of the correlations differed significantly between the German and Chinese (total) samples (all p-values of Fisher’s z-tests > 0.107).

值得注意的是,德国和中国(总)样本之间的相关性没有显著差异(Fisher z 检验的所有 p 值 > 0.107)。

As seen in Table 5, also in the male and female German and Chinese samples, there were moderate to strong positive correlations of the ATAI Acceptance scale with the items on the willingness to use specific AI products. On the other hand, there were weak to moderate negative correlations of the ATAI Fear scale with these items (several of the correlations were not significant). There was only one exception: The correlation between the ATAI Fear scale and the item on the willingness to use Pepper in the German male sample was just above zero.

如表 5 所示,同样在德国和中国的男性和女性样本中,ATAI 接受量表与使用特定 AI 产品的意愿项目存在中度到强的正相关。另一方面,ATAI 恐惧量表与这些项目存在弱到中度的负相关(其中一些相关性不显著)。只有一个例外:ATAI 恐惧量表与德国男性样本中愿意使用 Pepper 的项目之间的相关性略高于零。

表 5 两种 ATAI 量表之间的部分 Spearman 相关性以及德国和中国样本中关于使用特定 AI 产品意愿的项目,按性别划分

There were significant differences between German males and females in the correlations between the ATAI Acceptance scale and the item on the willingness to use self-driving cars (z = 2.22, p = 0.026) and the correlations between the ATAI Fear scale and the item on the willingness to use Pepper (z = 2.08, p = 0.037). No significant differences in any of the correlations were found between Chinese males and females (all p-values of Fisher’s z-tests > 0.176).

德国男性和女性在 ATAI 接受量表与使用自动驾驶汽车意愿项目之间的相关性 (z = 2.22, p = 0.026) 以及 ATAI 恐惧量表与使用 Pepper 意愿项目之间的相关性 (z = 2.08, p = 0.037) 之间存在显著差异。中国男性和女性之间未发现任何相关性存在显著差异 (Fisher z 检验的所有 p 值 > 0.176)。

There was a significant difference between German and Chinese males in the correlations between the ATAI Fear scale and the item on the willingness to use Pepper (z = 2.11, p = 0.035). No significant differences in any of the correlations were found between German and Chinese females (all p-values of Fisher’s z-tests > 0.128).

德国和中国男性在 ATAI 恐惧量表与使用 Pepper 意愿之间的相关性方面存在显着差异 (z = 2.11,p = 0.035)。德国女性和中国女性之间未发现任何相关性存在显著差异(Fisher z 检验的所有 p 值 > 0.128)。

4 Discussion 4 讨论

The present study aimed to develop and introduce a short, valid, and reliable measure to assess the Attitude Towards Artificial Intelligence (ATAI scale) in the different languages of German, Chinese, and English.

本研究旨在开发和引入一种简短、有效和可靠的措施来评估德语、中文和英语不同语言的人工智能态度(ATAI 量表)。

PCAs in each sample from Germany, China, and the UK consistently demonstrated that the ATAI scale consists of two negatively related scales describing Acceptance and Fear of AI. CFAs revealed mostly acceptable model fits in the three different samples. However, unexpectedly, the fifth item (“Artificial intelligence will cause many job losses.”) did not load strongly on the ATAI Fear factor, especially in the Chinese sample (standardized loading: 0.23). A similar pattern was found in the German and UK samples as well, where the loading of the same fifth item was not particularly high: Germany: 0.42, UK: 0.29. Excluding the fifth item would lead to a higher model fit, especially in the Chinese sample. Nevertheless, invariance analyses would still confirm “only” equal loadings. Overall, these findings indicate that job loss due to AI might not be a reason to have a negative attitude or even fear AI, especially in the present Chinese sample. This might be explained by the fact that part of the data (N = 284) was collected at a technology-oriented university (UESTC, Chengdu, China). Hence, the students here are most likely taught to create and work alongside AI. Their employment after university will potentially include working with AI products. Additionally, with an unemployment rate of around 4% [36], unemployment may not be considered a serious problem by Chinese students at all. However, according to the present results, students in Western countries also do not seem to see job loss as a serious reason to fear AI. In other samples that include more employed people being at a risk of losing their jobs due to AI progress, the fifth item might load more strongly on the ATAI Fear factor. Therefore, future researchers need to decide on the inclusion or exclusion of the fifth item by taking into account specific sample characteristics.

来自德国、中国和英国的每个样本中的 PCA 一致表明,ATAI 量表由两个负相关的量表组成,描述对 AI 的接受度和恐惧度。CFA 揭示了三个不同样本中基本可接受的模型拟合度。然而,出乎意料的是,第五项(“人工智能将导致许多失业”)并没有强烈地加载 ATAI 恐惧因子,尤其是在中国样本中(标准化加载:0.23)。在德国和英国的样本中也发现了类似的模式,其中相同的第五项的负载不是特别高:德国:0.42,英国:0.29。排除第 5 项将导致更高的模型拟合度,尤其是在中国样本中。尽管如此,不变性分析仍会确认“仅”相等的载荷。总体而言,这些发现表明,人工智能导致的失业可能不是持消极态度甚至害怕人工智能的理由,尤其是在目前的中国样本中。这可能是因为部分数据 (N = 284) 是在一所技术型大学(UESTC,中国成都)收集的。因此,这里的学生很可能被教导与 AI 一起创造和工作。他们大学毕业后的工作可能包括使用 AI 产品。此外,由于失业率约为 4% [36],中国学生可能根本不认为失业是一个严重的问题。然而,根据目前的结果,西方国家的学生似乎也没有将失业视为害怕人工智能的重要原因。在其他样本中,包括更多就业人员因 AI 进步而面临失业风险,第五项可能更强烈地加载 ATAI 恐惧因子。 因此,未来的研究人员需要通过考虑特定的样本特征来决定是否包含第五项。

Of major interest to the discussion on fear of AI and its association with job loss is a recent work by Granulo, Fuchs, and Puntoni [37]. In a series of studies, the researchers found that people prefer replacement of other human employees by other humans as opposed to by machines/robots/new technologies. But when it comes to their own current job and its potential loss, people prefer being replaced by machines/robots/new technologies rather than being replaced by other humans. The latter result was explained by higher self-threat when the own job is at risk to be carried out by another human as opposed to by a machine/robot/new technology [37]. These findings indicate that the perspective, whether one’s own or another one’s job is at risk for being replaced by AI, might also influence the attitude towards AI.

关于对人工智能的恐惧及其与失业关系的讨论主要感兴趣的是 Granulo、Fuchs 和 Puntoni 最近的一项工作 [37]。在一系列研究中,研究人员发现,人们更喜欢用其他人取代其他人类员工,而不是机器/机器人/新技术。但是,当谈到他们自己目前的工作及其潜在的损失时,人们宁愿被机器/机器人/新技术取代,也不愿被其他人取代。后一种结果可以用更高的自我威胁来解释,当自己的工作有可能由另一个人而不是机器/机器人/新技术来完成时[37]。这些发现表明,无论一个人自己的工作还是他人的工作有被人工智能取代的风险,这种观点也可能影响对人工智能的态度。

The Chinese sample showed highest scores on the ATAI Acceptance scale and lowest scores on the ATAI Fear scale (exception: Chinese males showed descriptively higher scores in the Fear scale than German males). This is in accordance with the enormous amount of human resources, time, and money invested into AI in China [38, 39]. It is also in line with the rising impact of Chinese research in the field of AI [40]. However, it might also be partly explained by recruitment of some participants at a technologically oriented university (UESTC, Chengdu, China), as previously mentioned. In line with previous literature on technology acceptance [18, 19], males demonstrated higher scores in the ATAI Acceptance scale than females, who in turn showed higher scores in the ATAI Fear scale. This gender difference was, however, substantially smaller in the Chinese sample. Perhaps, gender differences in technological research questions are generally smaller in China, though this implication requires further exploration. Also, the fact that we collected part of the data from China at a more technologically oriented university (UESTC, Chengdu, China) might explain the lack of significant gender differences in the Chinese sample. Overall, the findings from Germany, the UK, and the trend in China are in line with earlier research demonstrating that males are more interested in, and have a more positive attitude towards technologies [18, 19]. However, here it is worth mentioning that there is conflicting evidence [41]. These contradicting findings might be explained by the fact that gender differences in attitudes towards technology and technology acceptance vary depending on the domain of the technology [42]. For example, the notion that males generally hold more favourable attitudes towards technology has been challenged in recent years by females using specific digital platforms, such as online social networks, more than males do [43]. These findings point toward investigating different fields of AI and its products in future studies when investigating gender effects.

中国样本在 ATAI 接受量表上得分最高,在 ATAI 恐惧量表上得分最低(例外:中国男性在恐惧量表中的得分明显高于德国男性)。这与中国在 AI 上投入的大量人力资源、时间和金钱相一致 [38, 39]。这也与中国研究在人工智能领域日益增长的影响相一致 [40]。然而,如前所述,这也可能部分是由于在技术型大学(UESTC,中国成都)招募了一些参与者。与之前关于技术接受度的文献 [18, 19] 一致,男性在 ATAI 接受量表中的得分高于女性,而女性在 ATAI 恐惧量表中的得分更高。然而,这种性别差异在中国样本中要小得多。也许,中国技术研究问题的性别差异通常较小,尽管这种影响需要进一步探索。此外,我们在一所技术性更强的大学(UESTC,中国成都)收集了来自中国的部分数据,这一事实可能解释了中国样本中没有显著的性别差异。总体而言,德国、英国和中国的趋势与早期研究一致,表明男性对技术更感兴趣,对技术的态度也更积极 [18, 19]。然而,这里值得一提的是,存在相互矛盾的证据 [41]。这些相互矛盾的发现可能是因为对技术的态度和技术接受度的性别差异因技术领域而异 [42]。 例如,近年来,男性通常对技术持更有利态度的观念受到女性比男性更多地使用特定数字平台(如在线社交网络)的挑战[43]。这些发现表明,在未来的研究中,在调查性别影响时,可以调查人工智能及其产品的不同领域。

Moreover, in the present study the validity of the ATAI scale was tested by relating it to the items on the willingness to use specific AI products. Here, there are sound implications for the proposed measure, in that the ATAI Acceptance scale was positively associated with these items, whereas the ATAI Fear scale was inversely correlated with these items in both the German and Chinese samples.

此外,在本研究中,通过将 ATAI 量表与使用特定 AI 产品的意愿项目相关联来检验 ATAI 量表的有效性。在这里,拟议的措施有合理的意义,因为 ATAI 接受量表与这些项目呈正相关,而 ATAI 恐惧量表与德国和中国样本中的这些项目呈负相关。

Nevertheless, some limitations of the study need to be discussed. First of all, the samples are skewed with respect to the gender distribution. Specifically, there was a higher number of females in the German sample and the sample from the UK, and a higher number of males in the Chinese sample. However, this problem was counteracted by presenting descriptive statistics and correlations with the items on the willingness to use specific AI products separately for males and females of each sample (of note, correlations with the willingness to use specific products were not calculated in the sample from the UK). These correlations were, with single exceptions, equally pronounced across males and females. Moreover, the present samples mostly comprised rather young adults. Therefore, the generalizability of the results and applicability of the scale in older (or even younger) samples need to be investigated in future research. Additionally, the items were constructed based on rational choices and content of recent media debates. However, the items were not extracted out of a bigger item pool based on an exploratory factorial analysis/PCA. This might be seen as a shortcoming of the questionnaire. Nevertheless, the present scale clearly provides high face validity. As can be seen from the results, it seems to validly assess one’s attitude towards AI; but associations with other relevant constructs such as the Technology Acceptance Model (see below) need to be tested in the future. Moreover, we mention that we aimed to develop a brief scale to assess an individual’s attitude towards AI in different languages (here English, Chinese, and German) and this limited us in generating a large item pool immediately being available in the aforementioned languages. Such a large item pool brings advantages in terms of choosing the best possible items to assess latent constructs such as assessed with the ATAI scale but this was not possible against the background of lacking economic resources. Therefore, we name this explicitly as a limitation, in particular when future researchers aim to design scales giving insights into facets of such an attitude. This said, we believe our measure gives highly needed insights into general, broad attitudes towards AI, but without giving insights into such facets. Lastly, equal loadings could be assumed across all samples. However, scalar measurement invariance (equal intercepts; the next step after equal loadings) was not found. Therefore, the results regarding the mean value comparison of the two ATAI scales between the samples from different countries need to be interpreted with caution. Yet, we are of the opinion that reporting these results is important for understanding the data and for completeness of the reported results. Additionally, the results in all samples, especially the correlations between the ATAI scales and the items on the willingness to use specific AI products, were similar, underlining the cross-cultural applicability of our measure (see also a recent comment by Montag [44] pointing out that cross-cultural research might be an effective solution for the replication crisis).

尽管如此,该研究的一些局限性仍需讨论。首先,样本在性别分布方面存在偏差。具体来说,德国样本和英国样本中的女性数量较高,而中国样本中的男性数量较高。然而,通过提供描述性统计数据和与每个样本中男性和女性分别使用特定 AI 产品的意愿的相关性来抵消这个问题(值得注意的是,在英国的样本中没有计算与使用特定产品意愿的相关性)。除了少数例外,这些相关性在男性和女性中同样明显。此外,目前的样本大多由相当年轻的成年人组成。因此,在未来的研究中需要研究结果的普遍性和量表在较老(甚至更年轻)样本中的适用性。此外,这些项目是根据最近媒体辩论的理性选择和内容构建的。但是,这些项目不是根据探索性因子分析/PCA 从更大的项目池中提取出来的。这可能被视为问卷的缺点。尽管如此,目前的量表显然提供了很高的面效度。从结果中可以看出,它似乎有效地评估了一个人对 AI 的态度;但与其他相关结构的关联,例如技术接受模型(见下文))需要在将来进行测试。此外,我们提到我们的目标是开发一个简短的量表来评估不同语言(这里是英语、中文和德语)的个人对 AI 的态度,这限制了我们生成一个以上述语言立即可用的大型项目池。 如此大的项目池在选择最佳项目来评估潜在结构方面带来了优势,例如使用 ATAI 量表进行评估,但在缺乏经济资源的背景下这是不可能的。因此,我们将其明确命名为限制,特别是当未来的研究人员旨在设计量表来深入了解这种态度的各个方面时。也就是说,我们认为我们的衡量标准提供了对 AI 的一般、广泛态度的非常必要的见解,但没有提供对这些方面的见解。最后,可以假设所有样品的载荷相等。然而,未找到标量测量不变性(相等截距;相等载荷后的下一步)。因此,需要谨慎解释来自不同国家样本之间两个 ATAI 量表的平均值比较结果。然而,我们认为,报告这些结果对于理解数据和报告结果的完整性非常重要。此外,所有样本的结果,特别是 ATAI 量表与使用特定 AI 产品意愿项目之间的相关性,都是相似的,这强调了我们测量的跨文化适用性(另见 Montag [44] 最近的评论,指出跨文化研究可能是复制危机的有效解决方案)。

Importantly, the present ATAI scale measures the overall attitude towards AI. It might also be interesting to use this scale to address the attitude towards AI in specific contexts, such as traffic, medicine, etc. Moreover, we would like to acknowledge that AI has an emerging impact on daily life beyond the current examples of AI products. It was intentional to focus on products, which are either already in use in everyday life or can be explained to and understood by laypersons not working in the field of AI. Therefore, the present study represents a mere starting point to develop broader measures to assess one’s attitude towards AI. This could be the inclusion of facets such as the preference for interactions with AI products instead of interactions with real humans, or scales based on the Negative Attitude towards Robots Scale [45]. Additionally, future studies should investigate the reasons why people tend to accept or fear AI. For example, it could be due to the (or lack of) experience with AI products, societal norms, or subjective attitudes. Besides that, based on the Technology Acceptance Model, one could further investigate the impact of perceived ease of usage and perceived usefulness of AI products on the attitude towards distinct AI products [46, 47].

重要的是,目前的 ATAI 量表衡量的是人们对人工智能的整体态度。使用这个量表来解决特定环境(例如交通、医学等)对 AI 的态度也可能很有趣。此外,我们想承认,人工智能对日常生活的影响超出了目前的人工智能产品示例。它有意专注于产品,这些产品要么已经在日常生活中使用,要么可以向非人工智能领域工作的外行解释和理解。因此,本研究只是开发更广泛措施来评估一个人对人工智能的态度的起点。这可能是包括一些方面,例如偏好与人工智能产品交互而不是与真实人类交互,或者基于对机器人的消极态度量表[45]。此外,未来的研究应该调查人们倾向于接受或害怕人工智能的原因。例如,这可能是由于(或缺乏)使用 AI 产品的经验、社会规范或主观态度。除此之外,基于技术接受模型,人们可以进一步研究人工智能产品的感知易用性和感知有用性对不同人工智能产品的态度的影响 [46, 47]。

In conclusion, the present study contributes to the field of AI research by providing a short, reliable, and valid measure of the attitude towards AI as a starting point for further investigations of AI in the future.

总之,本研究通过提供对 AI 态度的简短、可靠和有效的衡量标准,作为未来进一步研究 AI 的起点,为 AI 研究领域做出了贡献。

References 引用

Fetzer JH (1990) What is artificial intelligence? In: Fetzer JH (ed) Artificial intelligence: its scope and limits. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 3–27

Fetzer JH (1990) 什么是人工智能?在:Fetzer JH (ed) 人工智能:其范围和限制。施普林格,多德雷赫特,第 3-27 页Mozur P (2017) Google’s AlphaGo defeats Chinese Go master in win for A.I. N. Y Times, New York. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/23/business/google-deepmind-alphago-go-champion-defeat.html. Accessed 3 Sept 2019

Mozur P (2017) 谷歌的 AlphaGo 击败中国围棋大师,为纽约 A.I. N. Y Times 获胜。https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/23/business/google-deepmind-alphago-go-champion-defeat.html。2019 年 9 月 3 日访问Jotham I (2017) Google’s AI clones itself and is smarter and more powerful than the man-made one. Int. Bus Times, London. https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/googles-ai-clones-itself-smarter-more-powerful-man-made-one-1643413. Accessed 3 Sept 2019

Jotham I (2017) 谷歌的人工智能克隆了自己,比人造的更聪明、更强大。国际巴士时报,伦敦。https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/googles-ai-clones-itself-smarter-more-powerful-man-made-one-1643413。2019 年 9 月 3 日访问Birdsall M (2014) Google and ITE: the road ahead for self-driving cars. Inst Transp Eng J 84:36–39

Lankau R (2015) Fragen Sie Alexa. Die Entmündigung des Individuums durch die Vermessung der Welt. In: Dammer K-H, Vogel T, Wehr H (eds) Zur Aktualität der Kritischen Theorie für die Pädagogik. Springer, Wiesbaden, pp 277–297

Sandoval EB, Mubin O, Obaid M (2014) Human robot interaction and fiction: a contradiction. In: Beetz M, Johnston B, Williams M-A (eds) Social robotics. Springer, Berlin, pp 54–63

Glas DF, Minato T, Ishi CT, Kawahara T, Ishiguro H (2016) ERICA: The ERATO intelligent conversational android. In: 2016 25th IEEE International symposium on robot and human interactive communication (RO-MAN), pp 22–29

Boston Dynamics Atlas®|Boston dynamics. https://www.bostondynamics.com/atlas. Accessed 10 Jan 2020

Markoff J (2013) Modest Debut of Atlas May Foreshadow Age of ‘Robo Sapiens’. N. Y Times, New York. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/12/science/modest-debut-of-atlas-may-foreshadow-age-of-robo-sapiens.html. Accessed 1 Jan 2020

Hamet P, Tremblay J (2017) Artificial intelligence in medicine. Metabolism 69:36–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2017.01.011

France-Presse A (2016) Robot receptionists introduced at hospitals in Belgium. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/jun/14/robot-receptionists-hospitals-belgium-pepper-humanoid. Accessed 6 Sept 2019

Loesche D (2017) Die gesellschaftlichen Kosten der digitalen Revolution. https://de.statista.com/infografik/11381/automatisierung-der-arbeitswelt/. Accessed 3 Sep 2019

Wilson JH, Daugherty PR, Morini-Bianzino N (2017) The jobs that artificial intelligence will create. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 58:13–16

Sánchez Nicolás E (2019) All “big five” tech firms listened to private conversations. In: EUobserver. https://euobserver.com/science/145759. Accessed 3 Sep 2019

Statista (2019) Sehen Sie künstliche Intelligenz grundsätzlich als Bedrohung oder als Chance? https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/977622/umfrage/umfrage-zu-assoziationen-mit-dem-begriff-kuenstliche-intelligenz-in-der-schweiz/. Accessed 3 Sep 2019

Cellan-Jones R (2014) Stephen Hawking warns artificial intelligence could end mankind. BBC News, London. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-30290540. Accessed 6 Sept 2019

Gibbs S (2014) Elon Musk: artificial intelligence is our biggest existential threat. The Guardian, London. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/oct/27/elon-musk-artificial-intelligence-ai-biggest-existential-threat. Accessed 6 Sept 2019

Cai Z, Fan X, Du J (2017) Gender and attitudes toward technology use: a meta-analysis. Comput Educ 105:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.11.003

Kuo IH, Rabindran JM, Broadbent E, Lee YI, Kerse N, Stafford RMQ, MacDonald BA (2009) Age and gender factors in user acceptance of healthcare robots. In: RO-MAN 2009—the 18th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication, pp 214–219

Marsden P (2017) Sex, lies and A.I. https://assets.website-files.com/59c269cb7333f20001b0e7c4/59d7792c6e475e0001de1a2c_Sex_lies_and_AI-SYZYGY-Digital_Insight_Report_2017_DE.pdf. Accessed 12 Sept 2019

R Core Team (2018) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

RStudio Team (2015) RStudio: integrated development for R. R. RStudio Inc., Boston

Fox J, Weisberg S (2019) An R companion to applied regression, 3rd edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks

Wickham H, François R, Henry L, Müller K (2019) dplyr: a grammar of data manipulation. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr

Torchiano M (2019) Effsize: efficient effect size computation. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=effsize

Warnes GR, Bolker B, Lumley T, SAIC-Frederick and RCJC from RCJ are C (2018) Program IF by the IR, NIH of the Institute NC, NO1-CO-12400 C for CR under NC (2018) gmodels: various R programming tools for model fitting. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gmodels

Bernaards C, Jennrich R (2005) Gradient projection algorithms and software for arbitrary rotation criteria in factor analysis. Educ Psychol Meas 65:676–696

Harrell FE Jr, with contributions from Charles Dupont and many others (2019) Hmisc: harrell miscellaneous. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gmodels

Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 48:1–36

Kim S (2015) Ppcor: partial and semi-partial (part) correlation. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gmodels

Revelle W (2019) psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research. Evanston, Illinois

Jorgensen TD, Pornprasertmanit S, Schoemann AM, Rosseel Y (2019) SemTools: useful tools for structural equation modeling. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semTools

Miles J, Shevlin M (2001) Applying regression and correlation: a guide for students and researchers. SAGE Publications, London

Tukey JW (1977) Exploratory data analysis, 1st edn. Pearson, Reading

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Eqn Model A Multi J 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Trading Economics (2019) China unemployment rate. https://tradingeconomics.com/china/unemployment-rate. Accessed 6 Sep 2019

Granulo A, Fuchs C, Puntoni S (2019) Psychological reactions to human versus robotic job replacement. Nat Hum Behav. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0670-y

CBS News (2017) China announces goal of leadership in artificial intelligence by 2030. CBS News, New York. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/china-announces-goal-of-leadership-in-artificial-intelligence-by-2030/. Accessed 10 Sept 2019

Pham S (2017) China wants to build a $150 billion AI industry. CNNMoney, London. https://money.cnn.com/2017/07/21/technology/china-artificial-intelligence-future/index.html. Accessed 9 Sept 2019

Elsevier ArtificiaI Intelligence: how knowledge is created, transferred, and used; trends in China, Europe, and the United States. https://www.elsevier.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/906779/ACAD-RL-AS-RE-ai-report-WEB.pdf. Accessed 9 Sept 2019

Bain CD, Rice ML (2006) The influence of gender on attitudes, perceptions, and uses of technology. J Res Technol Educ 39:119–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2006.10782476

Goswami A, Dutta S (2016) Gender differences in technology usage—a literature review. Open J Bus Manag 04:51–59. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2016.41006

Montag C, Błaszkiewicz K, Sariyska R, Lachmann B, Andone I, Trendafilov B, Eibes M, Markowetz A (2015) Smartphone usage in the 21st century: who is active on WhatsApp? BMC Res Notes 8:331. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1280-z

Montag C (2018) Cross-cultural research projects as an effective solution for the replication crisis in psychology and psychiatry. Asian J Psychiatry 38:31–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2018.10.003

Syrdal DS, Dautenhahn K, Koay KL, Walters ML (2009) The negative attitudes towards robots scale and reactions to robot behaviour in a live human-robot interaction study. In: Adaptive and emergent behaviour and complex systems: Proceedings of the 23rd convention of the society for the study of artificial intelligence and simulation of behaviour, AISB 2009. SSAISB, 2009. pp 109–115

Davis FD (1985) A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems : theory and results. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Davis FD (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q 13:319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. Christian Montag was supported by the German Research Foundation (MO 2363/3-2). Cornelia Sindermann was stipend of the German Academic Scholarship Foundation (Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes). JW is Stipend of the German Academic Scholarship Foundation (Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CM designed the present study including the questionnaire to assess the Attitude Towards Artificial Intelligence (ATAI scale). CS and CM drafted the present manuscript. CS conducted the statistical analyses. MZ and PS have been responsible for the Chinese translation process of the questionnaires. CS, JW, ML, and BB conducted the data collection in China, whereas CS and RS collected the German data. MS, CM, and CS were responsible for the translation process in English language. Moreover, MS conducted the data collection in the UK. CS, HS, and BB conducted data collection for the control survey. All statistical analyses were independently checked by HS. All authors read, revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest statement.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sindermann, C., Sha, P., Zhou, M. et al. Assessing the Attitude Towards Artificial Intelligence: Introduction of a Short Measure in German, Chinese, and English Language. Künstl Intell 35, 109–118 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13218-020-00689-0