Consume less, create more

少消费,多创造

Modern technology makes us consumers instead of creators

现代科技使我们成为消费者而非创造者

Like most people, I like to sit on the bus, stare out at the zombies drooling over their phones, and feel smugly superior. I see their bored, lifeless eyes and pity these sheeple whose lives have been ruined in service of Big Tech profits.

像大多数人一样,我喜欢坐在公交车上,盯着那些对着手机流口水的僵尸们,感到自鸣得意。我看到他们那无精打采、毫无生气的眼睛,对这些为了大科技公司的利润而毁掉自己生活的羊群感到同情。

This lasts for about thirty seconds before I get bored. The guy next to me chuckles at something on Kanye’s Twitter feed. Wait Kanye? I thought he was off Twitter! In seconds my own phone is out, and I’m furiously scrolling through Reddit, looking for fresh memes.

这段持续大约三十秒,然后我就感到厌烦了。我旁边的家伙在侃爷的推特动态上笑出声。等等,侃爷?我以为他退出推特了!几秒钟后,我自己的手机也拿出来了,我疯狂地在 Reddit 上滚动,寻找新鲜的梗。

And so goes the common trope: we all hate our phones, social media, and Netlfix—but we also love them.

所以这就是常见的说法:我们所有人都讨厌我们的手机、社交媒体和 Netflix——但我们同时也爱它们。

Eventually tiring of plain-vanilla bus-ride superiority, I brought a book with me on the bus. Not a Kindle, or an iPad, but a bona fide bound book.

最终厌倦了普通的公交车优越感,我在公交车上带了一本书。不是 Kindle,也不是 iPad,而是一本真正的纸质书。

After every sentence or two I would gaze incredulously around the bus with a sneaky grin. These dumb cows, I thought, look at them melt their brains with their stupid social feeds. They can’t focus like I can. I was about to turn back to Sapiens when I noticed a woman in the back of the bus who wasn’t staring at her phone. Nor was she reading a book. She wasn’t even listening to a monotonous NPR podcast.

每两句话后,我就会惊奇地环顾公交车,脸上带着狡猾的微笑。这些愚蠢的牛,我想,看看他们如何用愚蠢的社交动态烧坏自己的脑子。他们无法像我一样集中注意力。我正要回头看向“智人”时,注意到车后有一位女士没有盯着手机。她也没有看书。她甚至没有在听乏味的 NPR 播客。

This psychopath was sketching. She had a charcoal pencil and was sketching a human figure. She didn’t look happy exactly. But she looked engaged. She looked intent. And all of a sudden my smugness fled. I realized that reading a book was really just like reading Reddit—both were consumptive activitives.

这个心理变态在画画。她拿着一支铅笔,正在画一个人形。她看起来并不开心,确切地说。但她看起来很投入。她看起来全神贯注。突然,我的得意感消失了。我意识到看书其实就像浏览 Reddit 一样——两者都是消耗性的活动。

Were previous generations really better off because they merely watched TV, or listened to radio, or read books? All of these activities are passive. All of these activities involve letting external thoughts temporarily replace your own.

前几代人真的因为只是看电视、听广播或读书就生活得更好了吗?所有这些活动都是被动的。所有这些活动都涉及到让外部思想暂时取代你自己的思想。

Today’s smartphones differ from medieval books only in degree—all media is created to be consumed.

今天的智能手机与中世纪的书籍只在程度上不同,所有媒体都是为了被消费而创造的。

I had to start creating.

我不得不开始创造。

Corín Tellado was a Spanish author who wrote over 5,000 books in her 81-year lifespan. That’s over sixty books a year, assuming she came out of the womb fully literate. She claimed she could write a book in two days, and I’m inclined to believe her.

科尔林·特拉多是一位西班牙作家,她在 81 年的生命中写了超过 5000 本书。如果假设她从出生起就完全识字,那么她每年大约能写出 60 本书。她声称可以在两天内写出一本书,我倾向于相信她。

I can’t write a tweet in two days. Nevertheless, I was inspired by Tellado to stop consuming and start creating.

我两天内无法撰写一条推文。然而,我受到了 Tellado 的启发,决定停止消费,开始创造。

If we categorize all our waking moments as either consumptive or creative, I was probably at a 10:1 ratio, and that’s only if I label “copy/pasting stock images into Keynote presentations” as “creative.” Tellado was probably closer to 1:1. How could I get closer to that?

如果我们将所有清醒时刻分类为消耗性或创造性,我可能的比例是 10:1,这还是在将“将库存图片粘贴到 Keynote 演示文稿中”视为创造性的情况下。Tellado 可能更接近 1:1 的比例。我如何才能更接近这个比例?

On my next bus ride I pulled out my phone and opened the iOS notes app. I created a new note titled Essay.

在下一次坐公交车的时候,我拿出了手机并打开了 iOS 笔记应用。我创建了一个新的笔记,标题为 Essay 。

I stared at that off-white screen for several long minutes without typing anything. I don’t have anything to write about, I thought. Also, I’m not even a good writer…maybe I should look online for some tips…

我盯着那块浅白色的屏幕看了好几分钟,什么也没打。我没什么可写的,我想。而且,我甚至不是一个好的作家……或许我应该上网找些技巧。

But that was a bad idea and I knew it. So I swallowed my pride and just started writing:

但那是个糟糕的主意,我知道。所以我放下自尊,开始写作:

Why I think creating stuff is a good thing.

我认为创造事物是一件好事。An essay by Tom C.

汤姆·C 的一篇文章

This was going to be rough.

这将会很艰难。

I think people consume too much, and don’t create enough. This is bad I think.

我认为人们消费过多,创造却不够。我觉得这是不好的。

Like, really rough. 像,真的很粗糙。

But I kept typing; pouring inane, kindergarten-level drivel into my phone.

但我继续打字;将幼稚、幼儿园水平的废话输入到我的手机中。

The average person can type about 20 words per minute on a phone. My commute is about 30 minutes each way, so that’s a maximum of 1,200 words a day. Realistically I’m going to have to spend some time thinking about what to write, so let’s be conservative and shoot for 500 words a day.

普通人使用手机时每分钟大约能打 20 个字。我的通勤时间单程大约 30 分钟,所以一天最多能打 1200 个字。实际上,我需要花时间思考要写什么,所以保守估计,我每天的目标是 500 个字。

I read somewhere that a good blog post is 1,600 words…so if I work fast I could pump one out every three days, right?

我在某个地方读到,一篇好的博客文章应该是 1600 个字……所以,如果我工作迅速,我可以每三天写出一篇,对吧?

The first day I wrote 100 horrible words. Really super bad. No one will ever see these words.

第一天我写了 100 个糟糕的单词。真的超级差。没有人会看到这些单词。

Day two I wrote 80 words. I think I psyched myself out over how bad the previous day went.

第二天我写了 80 个单词。我觉得自己对前一天的糟糕情况过于焦虑。

The third day I only kept writing out of stubbornness. I knew this project was doomed, but I felt like really dooming it.

第三天,我只是因为固执才继续写。我知道这个项目注定要失败,但我感觉自己真的让它失败了。

By then end of the first week I had 500 words in the bank. I didn’t feel good about it, but it felt slightly better than scrolling through 47 #AndThatsWhyYouAreMyEx tweets.

到第一周结束时,我已经有 500 个单词了。我不觉得这很好,但比浏览 47 条#AndThatsWhyYouAreMyEx 推文略好一些。

My essay was garbage. But it was my garbage.

我的文章是垃圾。但这却是我自己的垃圾。

So I kept at it, day after day. I once again started feeling smugly superior to my fellow bus riders. Look at me creating, I thought. Look at me contributing to the world, while these reptiles just distract themselves with their phones until they die.

所以我继续坚持,日复一日。我再次对同车的乘客感到自鸣得意。看我创造,我想。看我为世界做出贡献,而这些家伙只是用手机消磨时间,直到死去。

This arrogance lasts for a few seconds until I re-read the stream-of-consciousness dogshit I’m typing into my phone.

这种傲慢持续了几秒钟,直到我重新阅读我正在手机上输入的杂乱无章的自我意识垃圾。

I’ve never done sales, but I know a little bit about the “sales funnel.” You hire college grads to make 500 cold calls in a week. Of those 500 calls, maybe 5% agree to watch a demo of the product.

我从未做过销售,但我知道一点关于“销售漏斗”的知识。你雇佣大学毕业生每周进行 500 次冷呼。在这 500 次电话中,可能有 5%的人同意观看产品的演示。

Then some slightly-more-senior sales people do this demo, and perhaps 20% of those demos end up in contract negotiation. And 60% of those end up as actual sales. That means you need 500 cold calls to make three sales.

然后一些稍微资深的销售人员演示,大约 20%的演示最终进入合同谈判。其中 60%最终成为实际销售。这意味着你需要 500 次冷呼叫来促成三笔销售。

I think that’s what creating is like. You need to write 500 words to get three good ones. Or 500 sketches, business ideas, or recipes.

我认为创作就是这样的。你需要写出 500 个字,才能得到三个好的。或者 500 个草图、商业想法或食谱。

If you’re really really good, you can increase your overall conversion rate from 0.6% to 1%—but the most reliable way to get better results is to just produce more crap.

如果你真的非常出色,你可以将整体转化率从 0.6%提高到 1%——但获得更好结果最可靠的方法只是生产更多的垃圾内容。

So I kept at it. week after week. Sometime in the middle of the fourth week I had 3,000 words in my Notes app. That’s when I started editing.

所以我继续坚持,周复一 周。在第四周的某个时候,我在笔记应用中积累了 3000 个字。从那时起,我开始进行编辑。

Editing is hard because you realize how bad you are. But editing is easy because we’re all better at criticizing than we are at creating.

编辑工作很难,因为你意识到自己有多差。但编辑工作也很容易,因为我们所有人都在批评方面比在创造方面更擅长。

The good thing about forcing yourself to produce a bunch of garbage is that you don’t feel bad deleting it. You’re not married to any of your work, because you wrote it half-awake on the 1BX while some crazy dude negotiated his fare with the driver. I gleefully deleted hundreds of words, trying not to think about the neanderthal who must’ve written them.

强迫自己产生大量垃圾的好处是,你不会感到内疚将其删除。你对任何工作都不忠诚,因为你在 1BX 上半睡半醒时写下的,而一个疯狂的家伙正在与司机讨价还价。我高兴地删除了数百个单词,尽量不去想那个必须写下它们的原始人类。

It was exactly a month after I started this creative project that I finished this first essay. I read it over for the bazillionth time and thought this only a small tire fire.

我开始这个创意项目恰好一个月后,我完成了这篇第一篇散文。我反复读了无数遍,只觉得这就像一个小轮胎火灾。

In it’s final form, the essay was almost exactly 1,600 words. I called it Consume less, create more.

在最终形式下,这篇文章几乎正好有 1600 个单词。我称之为“减少消费,增加创造”。

You are, in fact, reading that essay right now. It may not look like it, but this is the product of an entire month of bus rides. If you live in San Francisco and saw someone on the 1BX smashing the face of his phone like he was angry at it, you probably saw me writing this essay.

实际上,你现在正在阅读这篇文章。它可能看起来不像这样,但这是整个一个月公交车行程的产物。如果你住在旧金山,并看到有人在 1BX 上用力打手机,好像对它很生气,你可能看到我在写这篇文章。

Perhaps three people will read this essay, including my parents. Despite that, I feel an immense sense of accomplishment. I’ve been sitting on buses for years, but I have more to show for my last month of bus rides than the rest of that time combined.

或许会有三个人阅读这篇文章,包括我的父母。尽管如此,我感到一种巨大的成就感。多年来我一直坐在公交车上,但我在过去一个月的公交车行程中所取得的成就,比之前所有时间加起来还要多。

Smartphones, I’ve decided, are not evil. This entire essay was composed on an iPhone. What’s evil is passive consumption, in all its forms.

智能手机,我决定,它们并非邪恶。这篇整篇文章就是在 iPhone 上撰写的。真正邪恶的是所有形式的被动消费。

Twitter, Facebook, Instagram—we can all agree that these are serious timewasters. But what about The Economist or War and Peace? How much can you really remember from all of those New York Times op-eds you’ve read? Could you summarize the major themes of Grapes of Wrath?

Twitter,Facebook,Instagram——我们都同意这些都是浪费时间的。但是《经济学人》或《战争与和平》呢?你真的能记住你读过的所有《纽约时报》社论吗?你能否总结《愤怒的葡萄》的主要主题?

Most knowledge worth having comes from practice. It comes from doing. It comes from creating. Reading about the trade war with China doesn’t make you smarter—it gives you something to say at dinner parties. It gives you the illusion that you have the vaguest idea what is happening in our enormously complex world.

大多数值得拥有的知识来自于实践。它来自于行动,来自于创造。关于中美贸易战的阅读并不能让你变得更聪明——它只是让你在晚宴上能有话可说。它让你产生一种错觉,以为自己对这个极其复杂的世界发生的事情有最起码的了解。

A lot of ink has been spilled about the perils of modern technology. How it distracts us, how it promotes unhealthy comparisons with others, how it makes us fat, how it limits social interaction, how it spies on us. And all of these things are probably true, to some extent.

关于现代科技的危险,已经写下了大量的墨水。它如何分散我们的注意力,如何与他人进行不健康的比较,如何让我们变胖,如何限制社交互动,如何监视我们。所有这些事情在一定程度上可能是真的。

But the real tragedy of modern technology is that it’s turned us into consumers. Our voracious consumption of media parallels our consumption of fossil fuels, corn syrup, and plastic straws. And although we’re starting to worry about our consumption of those physical goods, we seem less concerned about our consumption of information.

但现代科技的真正悲剧在于,它让我们成为了消费者。我们对媒体的贪婪消费与对化石燃料、玉米糖浆和塑料吸管的消费相平行。尽管我们开始担心对这些实体商品的消费,但我们似乎对信息的消费不太关心。

We treat information as necessarily good, and comfort ourselves with the feeling that whatever article or newsletter we waste our time with is actually good for us. We equate reading with self improvement, even though we forget most of what we’ve read, and what we remember isn’t useful.

我们将信息视为必然好的,用一种安慰自己的感觉来满足,即我们浪费时间阅读的每篇文章或新闻简报实际上对我们有益。我们将阅读等同于自我提升,尽管我们忘记了大部分读过的内容,而我们记得的内容也没有用处。

So stop reading and start creating. Paint, draw, compose, code, or plan. It will be hard. It will be slow. It will be frustrating. But I promise it will be worth it.

所以停止阅读,开始创造。画画,画画,作曲,编程,或者规划。这会很难。这会很慢。这会很令人沮丧。但我保证这将是值得的。

Subscribe to TJCX 订阅 TJCX

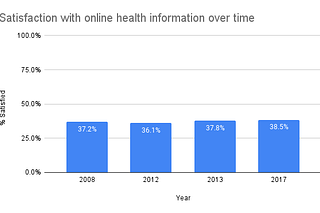

Mostly an exploration of consumer health information. Sometimes just a journal with extra steps.

主要是一种对消费者健康信息的探索。有时只是一本带有额外步骤的日记。