When Do We Stop Finding New Music? A Statistical Analysis When Do We Stop Finding New Music? A Statistical Analysis

我们什么时候停止寻找新音乐?统计分析我们什么时候停止寻找新音乐?统计分析

When does our taste in music stagnate? When does our taste in music stagnate?

我们的音乐品味什么时候会停滞不前?我们的音乐品味什么时候会停滞不前?

Intro: Spotify's Comfort Food DJ

简介:Spotify 的 Comfort Food DJ

I recently tried Spotify's new DJ feature in which an AI bot curates personalized listening sessions, introducing songs while explaining the intention behind its selections (much like a real-life disc jockey). Every four or five pieces, the bot interjects to set up its next block of music, ascribing a theme to these upcoming works. Here are some of my example introductions:

我最近尝试了 Spotify 的新 DJ 功能,其中人工智能机器人会策划个性化的聆听会话,介绍歌曲,同时解释其选择背后的意图(很像现实生活中的唱片骑师)。每隔四到五首作品,机器人就会插入并设置下一个音乐块,为这些即将推出的作品指定一个主题。以下是我的一些示例介绍:

"Next, we're gonna play some of your favorites from 2016."

“接下来,我们将播放一些您 2016 年最喜欢的歌曲。”"Here are some of your favorite indie rock songs from the 2010s."

“这里有一些您最喜欢的 2010 年代独立摇滚歌曲。”"Up next, we have some music inspired by your love of 2000s hip-hop."

“接下来,我们将推出一些受您对 2000 年代嘻哈音乐的热爱启发的音乐。”

With each DJ interlude, something became increasingly clear: my music taste had barely changed over the course of a decade. Armed with full knowledge of my musical interests, this AI agent had pinpointed my musical paralysis, packaging an algorithmic echo chamber of 2010s indie rock, 2000s pop, Bo Burnham, Blink-182, and Bruce Springsteen. Had my music taste stagnated?

随着每一次 DJ 插曲,一些事情变得越来越清晰:十年来我的音乐品味几乎没有改变。凭借对我的音乐兴趣的全面了解,这位 AI 代理准确地指出了我的音乐障碍,将 2010 年代独立摇滚、2000 年代流行音乐、Bo Burnham、Blink-182 和 Bruce Springsteen 的算法回声室打包在一起。我的音乐品味停滞了吗?

This minor existential tailspin sent me down a Google rabbit hole—I began frantically researching music paralysis and the science of sonic preference. Was this phenomenon of my own doing or a natural product of aging? Fortunately, the topic of song stagnation has been well-researched, aided by the robust datasets of streaming services.

这个存在主义的小混乱让我掉进了谷歌兔子洞——我开始疯狂地研究音乐瘫痪和声音偏好的科学。这种现象是我自己造成的还是衰老的自然产物?幸运的是,在流媒体服务强大的数据集的帮助下,歌曲停滞的话题已经得到了深入的研究。

So today, we'll explore how our relationship to music changes with age and the developmental phenomena driving our forever-shifting cultural tastes.

因此,今天,我们将探讨我们与音乐的关系如何随着年龄的增长而变化,以及推动我们不断变化的文化品味的发展现象。

When Do We Stop Finding New Music?

我们什么时候停止寻找新音乐?

Open-earedness refers to an individual's desire and ability to listen and consider different sounds and musical styling. Research has shown that adolescents exhibit higher levels of open-earedness, with a greater willingness to explore and appreciate diverse musical genres. During these years of sonic exploration, music gets wrapped up in the emotion and identity formation of youth; as a result, the songs of our childhood prove wildly influential over our lifelong music tastes.

开放性是指个人聆听和考虑不同声音和音乐风格的愿望和能力。研究表明,青少年表现出更高水平的开放性,更愿意探索和欣赏不同的音乐流派。在这些年的声音探索中,音乐融入了年轻人的情感和身份形成;因此,我们童年的歌曲对我们一生的音乐品味产生了巨大的影响。

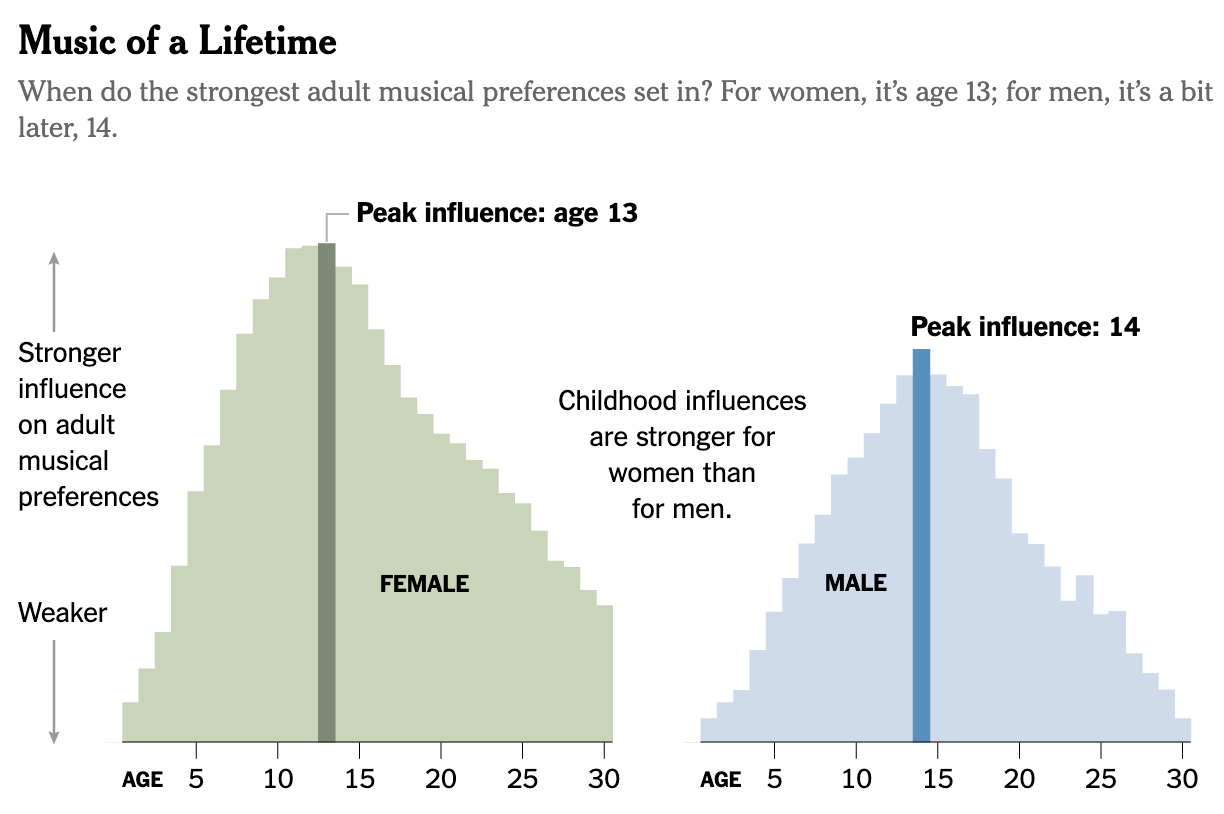

A New York Times analysis of Spotify data revealed that our most-played songs often stem from our teenage years, particularly between the ages of 13 and 16.

《纽约时报》对 Spotify 数据的分析显示,我们最常播放的歌曲通常源自青少年时期,尤其是 13 岁至 16 岁之间。

This finding has personal resonance, as I remember my cultural preferences being easily influenced during my pre-teen and early teenage years. For instance, I was twelve when Green Day released their landmark "American Idiot" album, a work that proved monumental in my relationship to music. Listening to the album's titular track felt like a supreme act of rebellion (for a twelve-year-old suburbanite). I was entranced by this song's iconoclastic spirit—could they actually say, "f**k America?"

这一发现引起了我个人的共鸣,因为我记得我的文化偏好在我青春期前和青少年早期很容易受到影响。例如,当 Green Day 发行他们具有里程碑意义的《American Idiot》专辑时,我才十二岁,这张专辑在我与音乐的关系中具有里程碑意义。听这张专辑的同名歌曲感觉就像是一种至高无上的反叛行为(对于一个十二岁的郊区人来说)。我被这首歌的反传统精神所吸引——他们真的会说“去他妈的美国吗?”

But "American Idiot" wasn't a true act of revolution. In fact, the album was produced and promoted by a multinational conglomerate with the intent of packaging seemingly transgressive pop-punk acts for my exact demographic. How was I so thoroughly seduced by this song? And yet, to this day, my visceral reaction to “American Idiot” is still one of euphoria, despite my cynicism. I guess I have no choice but to love this song forever (thanks to pre-teen me).

但《美国白痴》并不是真正的革命行为。事实上,这张专辑是由一家跨国集团制作和推广的,目的是为我的确切人群包装看似越轨的流行朋克表演。我怎么就被这首歌深深地吸引了呢?然而,直到今天,我对《美国白痴》的本能反应仍然是一种欣快感,尽管我对此持愤世嫉俗的态度。我想我别无选择,只能永远喜欢这首歌(感谢青春期前的我)。

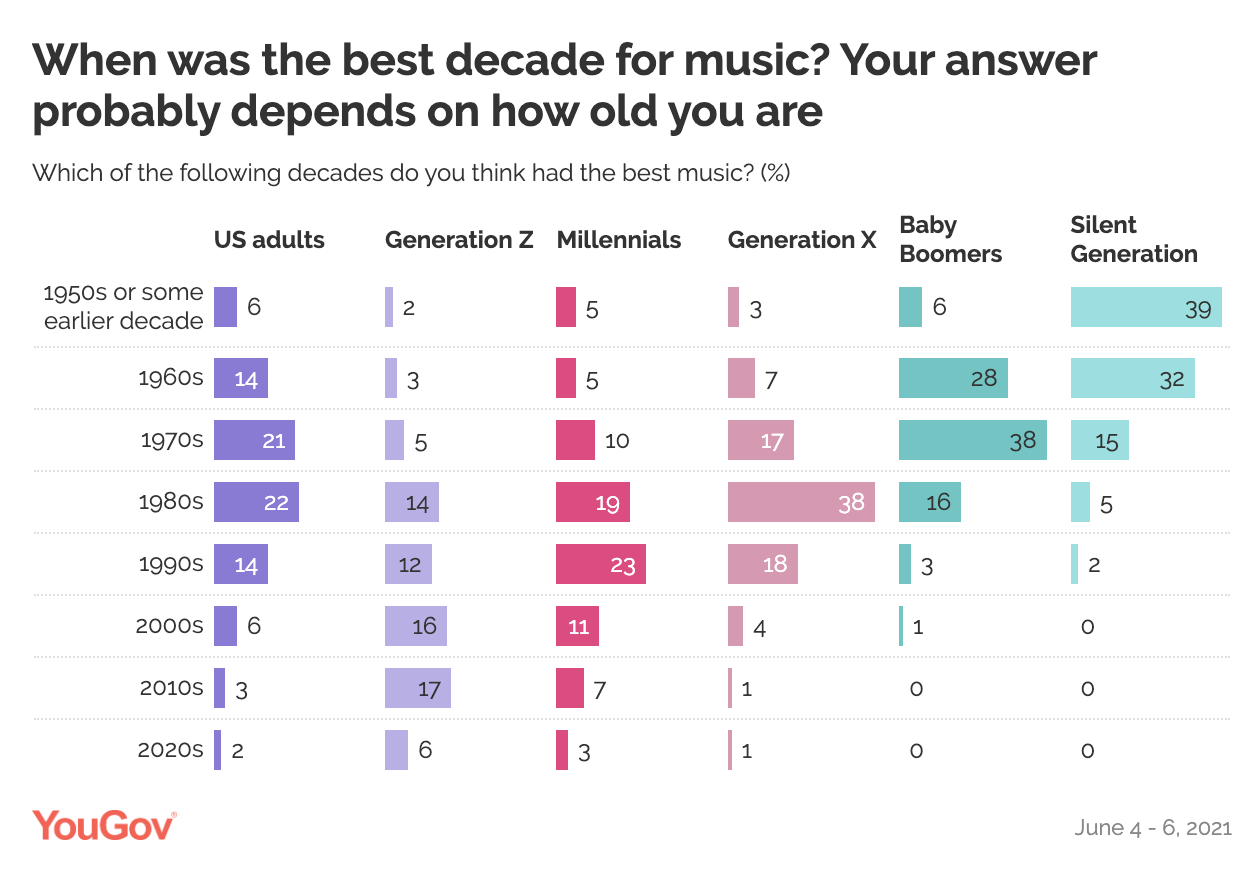

Indeed, YouGov survey data indicates a strong bias toward music from our teenage years, a phenomenon that is consistent across generations. Every cohort believes that music was "better back in my day."

事实上,YouGov 的调查数据表明,我们从青少年时期就对音乐产生了强烈的偏见,这种现象在各代人中都是一致的。每个群体都相信音乐“在我那个时代更好”。

Ultimately, cultural preferences are subject to generational relativism, heavily rooted in the media of our adolescence. It's strange how much your 13-year-old self defines your lifelong artistic tastes. At this age, we're unable to drive, vote, drink alcohol, or pay taxes, yet we're old enough to cultivate enduring musical preferences.

最终,文化偏好受到代际相对主义的影响,这种相对主义深深植根于我们青春期的媒体中。奇怪的是,13 岁的自己在多大程度上定义了你一生的艺术品味。在这个年龄,我们无法开车、投票、喝酒或纳税,但我们已经足够大了,可以培养持久的音乐偏好。

The pervasive nature of music paralysis across generations suggests that the phenomenon's roots go beyond technology, likely stemming from developmental factors. So what changes as we age, and when does open-eardness decline?

音乐瘫痪在几代人中普遍存在,这表明这种现象的根源超出了技术范围,很可能源于发展因素。那么,随着年龄的增长,什么会发生变化,开放性何时会下降呢?

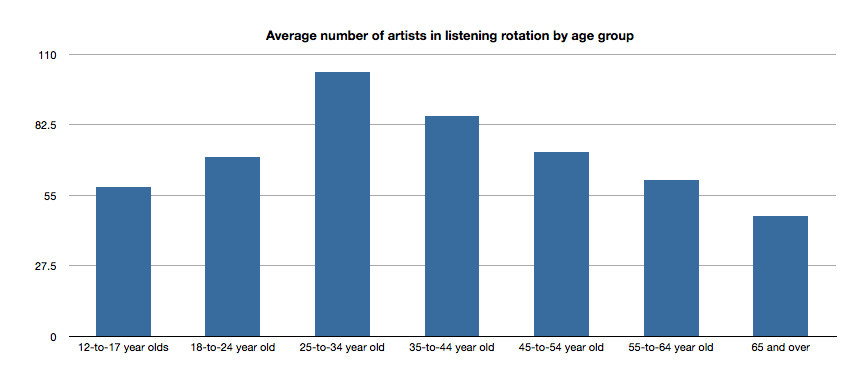

Survey research from European streaming service Deezer indicates that music discovery peaks at 24, with survey respondents reporting increased variety in their music rotation during this time. However, after this age, our ability to keep up with music trends typically declines, with respondents reporting significantly lower levels of discovery in their early thirties. Ultimately, the Deezer study pinpoints 31 as the age when musical tastes start to stagnate.

欧洲流媒体服务 Deezer 的调查研究表明,音乐发现量在 24 岁时达到顶峰,调查受访者表示,在此期间,他们的音乐循环更加多样化。然而,过了这个年龄,我们跟上音乐潮流的能力通常会下降,受访者表示,三十岁出头的发现水平明显较低。最终,Deezer 研究确定 31 岁是音乐品味开始停滞的年龄。

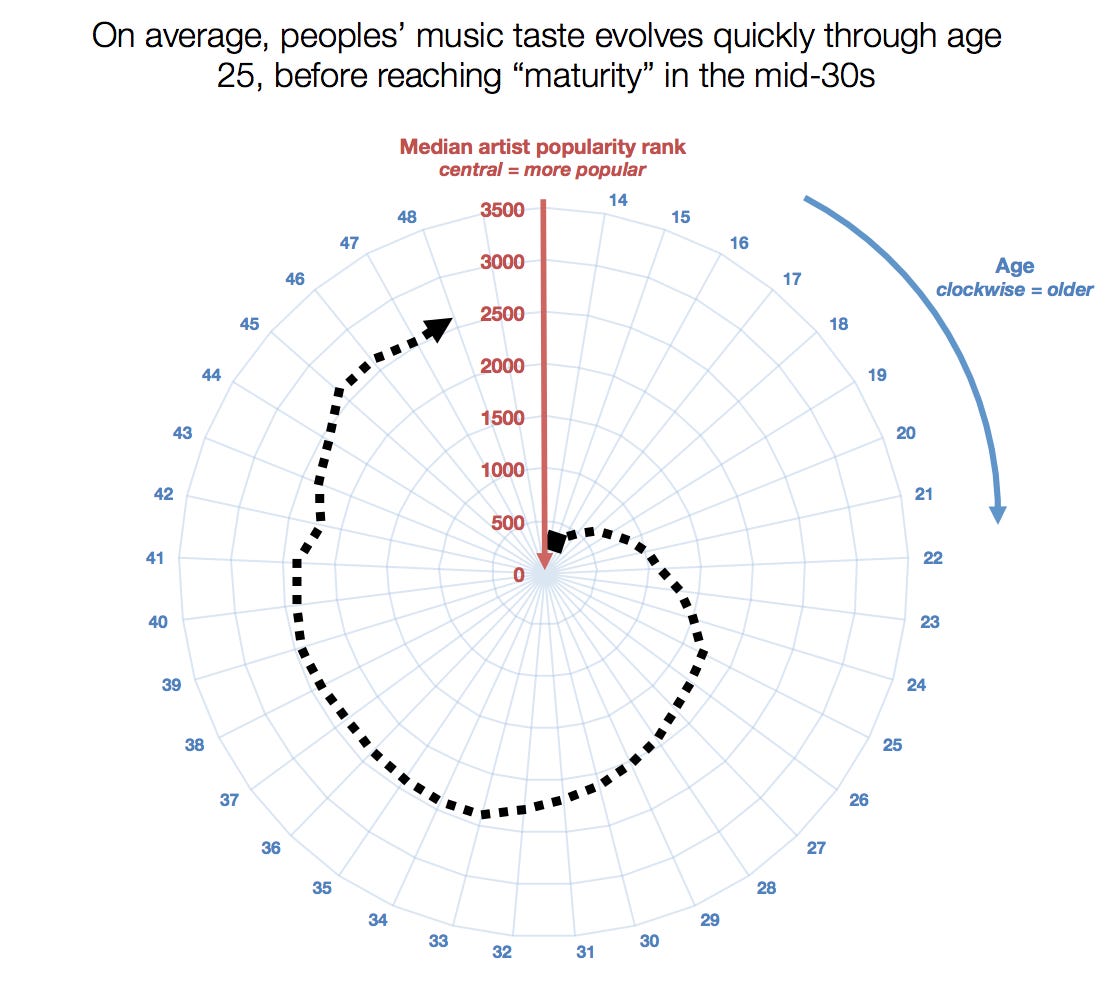

These findings have been replicated across numerous analyses, including a study of Spotify user data from 2014. Produced from Spotify's internal dataset, this research explores how tastes deviate from the mainstream with age. In this analysis, a contemporary pop star like Dua Lipa would score a 1 (the most popular), and an artist further out of the zeitgeist like Led Zeppelin would rank somewhere in the 200s. The resulting visual is unnerving as we observe our cultural preferences (quite literally) spiral away from the mainstream as we grow older.

这些发现已在众多分析中得到重复,包括对 2014 年 Spotify 用户数据的研究。这项研究根据 Spotify 的内部数据集生成,探讨了品味如何随着年龄的增长而偏离主流。在这个分析中,像 Dua Lipa 这样的当代流行歌星会得到 1 分(最受欢迎),而像 Led Zeppelin 这样远离时代精神的艺术家会排名在 200 左右。当我们观察到随着年龄的增长,我们的文化偏好(毫不夸张地)逐渐远离主流时,由此产生的视觉效果令人不安。

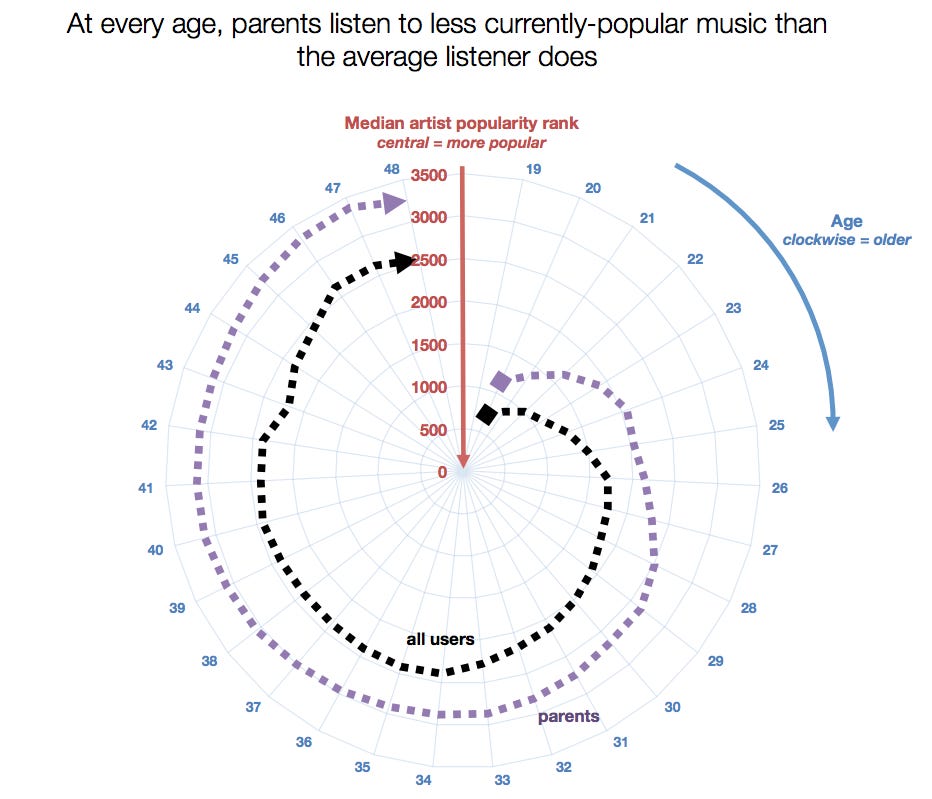

This study identifies 33 as the tipping point for sonic stagnation, an age where artistic taste calcifies, increasingly deviating from contemporary works. But wait, there's more. Spotify data indicates that parents stray from the mainstream at an accelerated rate compared to empty nesters—a sort of "parent tax" on one's cultural relevancy.

这项研究将 33 岁视为声音停滞的转折点,这是一个艺术品味钙化的时代,越来越偏离当代作品。但等等,还有更多。 Spotify 的数据表明,与空巢老人相比,父母偏离主流的速度更快——这是一种针对个人文化相关性的“父母税”。

But this stagnation goes beyond the popularity of our music selections; it's also the diversity across these works. From 30 onward, we listen to more music outside the mainstream and sample fewer artists during streaming sessions.

但这种停滞不只限于我们的音乐选择的受欢迎程度。这也是这些作品的多样性。从 30 岁开始,我们会听更多主流以外的音乐,并在流媒体会话中尝试更少的艺术家。

Reading these studies proved an existential body blow because I am 31, apparently on the precipice of becoming a musical dinosaur. I like to think I'm special—that my high-minded dedication to culture makes me an exceptionally unique snowflake—but apparently I'm just like everybody else. I turned 30, and now I'm in a musical rut, content to have an AI bot DJ pacify me with the songs of my youth.

阅读这些研究对我来说是一次重大的打击,因为我已经 31 岁了,显然正处于成为音乐恐龙的边缘。我喜欢认为自己很特别——我对文化的高尚奉献使我成为一片异常独特的雪花——但显然我和其他人一样。我已经 30 岁了,现在我已经陷入了音乐困境,满足于让人工智能机器人 DJ 用我年轻时的歌曲来安抚我。

I used to spend hours researching artists, scrutinizing my CD purchases, and, later, my iTunes selections. Musical exploration was an activity in and of itself; songs were more than background noise. Now, I'm stuck listening to James Blunt's "You're Beautiful" for the 1,000th time. What happened to me?

我曾经花几个小时研究艺术家、仔细检查我购买的 CD,以及后来我在 iTunes 上的选择。音乐探索本身就是一种活动。歌曲不仅仅是背景噪音。现在,我已经听了第一千遍 James Blunt 的《You're Beautiful》了。我发生什么事了?

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content?

喜欢到目前为止的文章并想要更多以数据为中心的流行文化内容吗?

Why Do We Stop Finding New Music?

为什么我们不再寻找新音乐?

Music paralysis is the product of both biological trends and practical constraints. Deezer survey respondents who identified as being "in a musical rut" cited numerous day-to-day limitations as cause for their stagnation, with the top three reasons being:

音乐麻痹是生物趋势和现实限制的产物。 Deezer 调查中那些认为自己“陷入音乐困境”的受访者表示,许多日常限制是他们停滞不前的原因,其中最主要的三个原因是:

Overwhelmed by the amount of choice available: 19%

因可供选择的数量而不知所措:19%Having a demanding job: 16%

工作要求较高:16%Caring for young children: 11%

照顾幼儿:11%

This first point regarding the paradox of choice is especially intriguing and would speak to streaming as some sort of societal ill, bombarding us with boundless content. It's easy to condemn Spotify for giving us too many options, but this complaint is likely emblematic of a broader developmental shift.

关于选择悖论的第一点特别有趣,它将流媒体视为某种社会病态,用无限的内容轰炸我们。人们很容易谴责 Spotify 为我们提供了太多选择,但这种抱怨很可能象征着更广泛的发展转变。

Context is critical to cultural discovery. An extensive cross-sectional study regarding musical attitudes and preferences from adolescence through middle age found that our relationship with music drastically changes over time. Surveying over 250,000 individuals, this study found:

背景对于文化发现至关重要。一项关于从青春期到中年的音乐态度和偏好的广泛横断面研究发现,我们与音乐的关系随着时间的推移而发生巨大变化。这项研究对超过 250,000 人进行了调查,结果发现:

The degree of importance attributed to music declines with age, even though adults still consider music important.

尽管成年人仍然认为音乐很重要,但音乐的重要性随着年龄的增长而下降。Young people listen to music significantly more than middle-aged adults.

年轻人听音乐的次数明显多于中年人。Young people listen to music in a wide variety of contexts and settings, whereas adults listen to music primarily in private contexts.

年轻人在各种各样的环境和环境中听音乐,而成年人主要在私人环境中听音乐。

The issue of music discovery does not originate from infinite choice; instead, this problem likely stems from decreased listenership and a waning commitment to exploration. Spending two hours a day combing through iTunes (now Spotify) is impractical. My priorities have changed, my emotional connection to music has changed, and I simply just don't have the time.

音乐发现的问题并非源于无限的选择,而是源于无限的选择。相反,这个问题可能源于听众数量的减少和对探索的承诺的减弱。每天花两个小时浏览 iTunes(现在的 Spotify)是不切实际的。我的优先事项已经改变,我与音乐的情感联系也已经改变,而我只是没有时间。

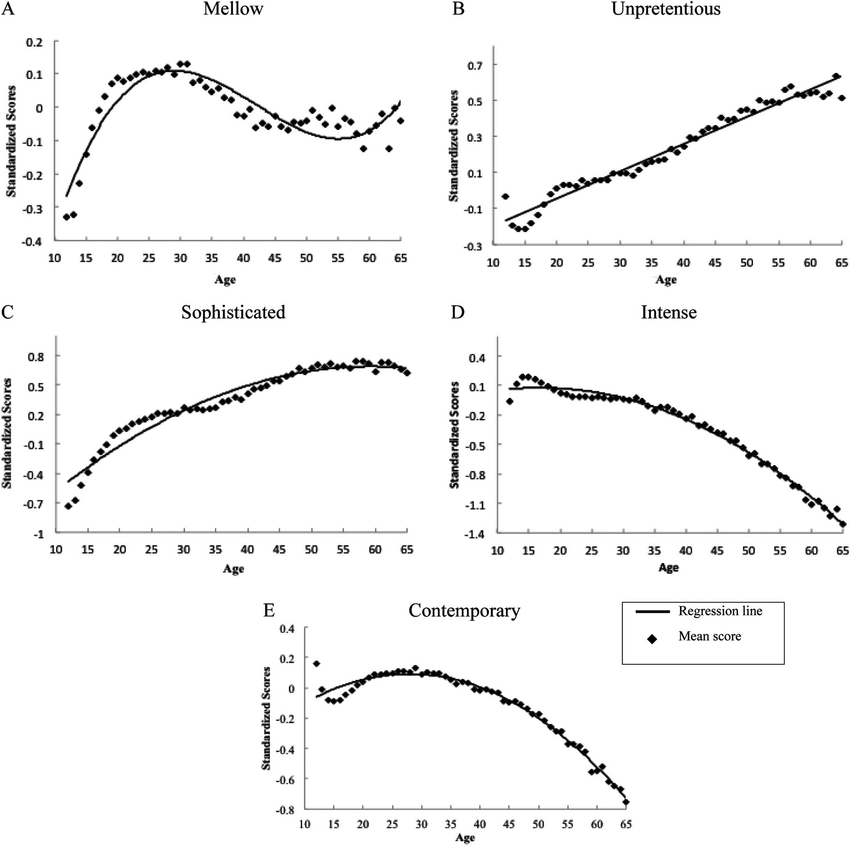

Indeed, this same cross-sectional study revealed that musical preferences are closely related to trends in psychosocial development. In this survey, researchers investigated how tastes vary across five dimensions as we age: intensity, contemporaneous, unpretentiousness, sophistication, and mellowness. The data they collected demonstrates a universality to our forever-changing relationship with music—it's natural to expect a progression in our preferences.

事实上,这项横断面研究表明,音乐偏好与心理社会发展趋势密切相关。在这项调查中,研究人员调查了随着年龄的增长,品味在五个维度上的变化:强度、同步、朴实、精致和醇厚。他们收集的数据证明了我们与音乐不断变化的关系的普遍性——我们很自然地期望我们的偏好会发生变化。

图片来源:“古往今来的音乐”

It's tempting to despair over these results, to accept changing cultural attitudes and the phenomenon of music paralysis as a predetermined truth. At the same time, stagnation is not a certainty. Research suggests that open-eardness and the discovery of new songs can be cultivated. Finding new music is a challenge, but it is achievable with dedicated time and effort. If we avoid the warm complacency of nostalgia, we can recapture our flare for music discovery.

人们很容易对这些结果感到绝望,并接受不断变化的文化态度和音乐瘫痪现象作为预定的事实。与此同时,停滞并不是必然的。研究表明,开放的态度和新歌的发现是可以培养的。寻找新音乐是一项挑战,但通过投入时间和努力是可以实现的。如果我们避免怀旧的热烈自满,我们就可以重新找回音乐发现的热情。

Final Thoughts: Music's Optimal Stopping Problem

最后的想法:音乐的最佳停止问题

My father "likes what he likes": Bruce Springsteen, Field of Dreams, The Washington Nationals, and consistently reminding me that Fleetwood Mac's Rumours was made after its bandmates divorced one another. Whenever I point out my dad's stubborn habits, he'll look at me, smile, and quote the immortal wisdom of Popeye: "I am what I am."

我父亲“喜欢他喜欢的东西”:布鲁斯·斯普林斯汀、梦想之地、华盛顿国民队,并不断提醒我弗利特伍德麦克的谣言是在其乐队成员相互离婚后制作的。每当我指出爸爸的顽固习惯时,他都会看着我,微笑着引用大力水手的不朽智慧:“我就是我。”

When I was younger, I strongly disliked this rationale. Surely, there is no fixed version of who we are. Humans are constantly evolving—perpetually engaged in self-discovery. But maybe this isn't the case for all facets of life.

当我年轻的时候,我非常不喜欢这个理由。当然,我们是谁并没有固定的版本。人类在不断进化——永远致力于自我发现。但也许生活的方方面面并非如此。

The explore-exploit trade-off refers to the dilemma between seeking new information (exploring) and optimizing decisions based on known information (exploiting). Some examples of the explore-exploit trade-off include:

探索-利用权衡是指寻求新信息(探索)和基于已知信息优化决策(利用)之间的困境。探索与利用权衡的一些例子包括:

Restaurant selection: Do you find a new restaurant or return to your old haunts?

餐厅选择:您会寻找新餐厅还是回到老地方?Movies: Do you watch something new or re-watch an all-time favorite?

电影:您会看一些新的东西还是会重新观看一直以来最喜欢的东西?Career: Should you keep your current job or look for a new one?

职业:你应该保留目前的工作还是寻找新的工作?

In the case of music discovery, exploring would consist of finding new songs and subgenres, while exploiting would entail listening to already-beloved tunes.

就音乐发现而言,探索包括寻找新歌曲和子流派,而利用则包括聆听已经喜爱的曲调。

The explore-exploit trade-off and an adjacent decision-making puzzle known as the optimal-stopping problem have prompted extensive research and the coining of a shortcut known as the 37% rule. This heuristic suggests we spend the first 37% of available search time exploring our options before settling on a preferred solution or selection.

探索与利用的权衡以及称为最优停止问题的相邻决策难题促使人们进行了广泛的研究,并创造了一种称为 37% 规则的捷径。这种启发式建议我们在确定首选解决方案或选择之前,先花 37% 的可用搜索时间探索我们的选项。

In the case of musical preference, the current American lifespan averages 80 years; when we multiply this figure by 37%, we get 30 years—coincidentally, the age at which music tastes stagnate. This back-of-the-envelope math could be interpreted in two ways:

就音乐偏好而言,目前美国人的平均寿命为80岁;当我们把这个数字乘以 37% 时,我们得到了 30 岁——巧合的是,到了这个年龄,音乐的味道就会停滞不前。这个粗略的数学可以用两种方式解释:

I am going crazy: I see numbers and symbols that don't mean anything. The 37% rule is a vague heuristic that may not even apply to this case, and I am perceiving order from true randomness.

我快要疯了:我看到的数字和符号没有任何意义。 37% 规则是一个模糊的启发式,甚至可能不适用于这种情况,而且我从真正的随机性中感知到了秩序。30 is our optimal stopping point: Despite the 37% rule being a highly generalized heuristic, there is some merit to doubling down on our favorites after a sustained period of searching—a phenomenon that appears to be our default state. We spend 30 years exploring new music, and once we've sampled enough works, we reach an optimal stopping point, comfortable with our rotation of artists and songs.

30 是我们的最佳停止点:尽管 37% 规则是一个高度概括的启发式规则,但在持续搜索一段时间后,加倍关注我们最喜欢的内容还是有一些优点的——这种现象似乎是我们的默认状态。我们花了 30 年的时间探索新音乐,一旦我们采样了足够多的作品,我们就达到了最佳的停止点,对艺术家和歌曲的轮换感到满意。

Maybe music paralysis is a feature, not a bug. Running on a never-ending treadmill of cultural exploration may be a recipe for discontent. There is nothing inherently wrong with "liking what you like." Is it my waning music discovery that's making me unhappy or the fact that I've yet to accept this reality?

也许音乐瘫痪是一个特征,而不是一个缺陷。在永无休止的文化探索跑步机上奔跑可能会导致不满。 “喜欢你喜欢的东西”本质上并没有什么错。是我对音乐的兴趣日渐减弱,还是我还没有接受这个现实,才让我不开心?

Perhaps I should forsake sonic exploration and exploit my love of "American Idiot," 2010s indie rock, 2000s pop, Bo Burnham, Blink-182, and Bruce Springsteen, content to live in an algorithmic echo chamber curated by DJ—my new AI savior.

也许我应该放弃声音探索,利用我对“美国白痴”、2010 年代独立摇滚、2000 年代流行音乐、Bo Burnham、Blink-182 和 Bruce Springsteen 的热爱,满足于生活在 DJ(我的新 AI 救星)策划的算法回声室中。

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

想讨论数据和统计吗?有有趣的数据项目吗?只是想打个招呼吗?电子邮件 daniel@statsignificant.com

Super interesting stuff, although interestingly none of it applies to me. I’m 32, and I’m still constantly discovering new music. I have always been hungry for more new sounds my whole life. I was actually more conservative as a kid, because kids tend to only like what’s hip, mainstream, or at least commercially accessible in some way. Now I like more extreme kinds of music.

超级有趣的东西,尽管有趣的是它们都不适合我。我已经 32 岁了,但我仍在不断发现新音乐。我一生都渴望更多新的声音。事实上,我小时候比较保守,因为孩子们往往只喜欢时髦的、主流的,或者至少在某种程度上可以商业化的东西。现在我喜欢更极端的音乐。

I'm in my 50s, and don't listen to much music at all, but I least want to listen to the songs of my youth. I heard them too much when they were new. I'm Gen-X, and if I had to pick a "best" era for music I'd probably say the 1940s or '50s.

我已经50多岁了,根本不怎么听音乐,但我最不想听年轻时的歌曲。当他们还是新人的时候,我听得太多了。我是 X 世代,如果我必须选择一个“最佳”音乐时代,我可能会说 20 世纪 40 年代或 50 年代。

My overall experience has been that when I was young I was into music that was new, and as I hit my late 20s I stopped caring about music. From age 35 to 40 a lot of sad things happened in my life, and music was a solace, so I became deeply involved in it, and discovered lots of then-new songs. Once life stopped being sad, I again stopped caring much about music.

我的总体经验是,当我年轻的时候,我喜欢新的音乐,当我二十多岁的时候,我不再关心音乐。从35岁到40岁,我的生活中发生了很多悲伤的事情,音乐是一种安慰,所以我深深地投入其中,发现了很多当时的新歌。一旦生活不再悲伤,我就不再关心音乐了。

I don't know if my experience is the norm, but I wonder if to at least some degree, when we are confused, sad, or otherwise unsure in our lives, music can console us, and once we grow up, get married, and have kids, and life is happier and more secure, we have less of a need for it.

我不知道我的经历是否是常态,但我想知道是否至少在某种程度上,当我们在生活中感到困惑、悲伤或其他不确定时,音乐可以安慰我们,一旦我们长大,结婚,有了孩子,生活更幸福、更安全,我们对它的需求就更少了。