- The construction of virtual reality

虛擬現實的建設 - Life = voyage, an equivalence expressed in the opening metaphor: “cammin di nostra vita” (path of our life), inherited from the “nuovo e mai non fatto cammino di questa vita” (the new and never before traveled path of this life) of Convivio 4.12.15

生命 = 航程,這在開頭的隱喻中表達出來:“cammin di nostra vita”(我們生命的道路),繼承自《宴會》第 4.12.15 中的“nuovo e mai non fatto cammino di questa vita”(這生命中新且從未走過的道路) - Divine love — “l’amor divino” — first caused the stars to move (Inf. 1.39-40), initiating the creation of the universe

神聖的愛——“l’amor divino”——首先使星星運行(《神曲》第一卷 1.39-40),啟動了宇宙的創造。 - The mixing of classical with Christian yields a uniquely hybrid “middling” textuality

將古典與基督教混合產生了一種獨特的混合“中庸”文本性 - To the traditional glosses of ”Nel mezzo”, which include Isaiah 38:10 and Horace’s Ars Poetica, I add:

對於「Nel mezzo」的傳統註解,包括以賽亞書 38:10 和賀拉斯的《詩藝》,我補充:- The existential mid-point, from Aristotle’s definition of time as a “kind of middle-point” in the Physics (Dante cites Aristotle on time in the Convivio) and

存在的中點,根據亞里士多德在《物理學》中對時間的定義為“某種中點”(但丁在《宴會》中引用了亞里士多德對時間的看法)和 - The ethical mezzo, from Aristotle’s definition of virtue as residing at the mean (cited by Dante in the canzone Le dolci rime and later in the Convivio)

倫理的中庸,根據亞里士多德對美德的定義,存在於中間(由但丁在《甜美的韻律》及後來的《宴會》中引用)

- The existential mid-point, from Aristotle’s definition of time as a “kind of middle-point” in the Physics (Dante cites Aristotle on time in the Convivio) and

- The voyager who is lost at sea and the Ulysses theme: on “Ulyssean” as an epithet in The Undivine Comedy and in this Commento

在海上迷失的航行者與《尤利西斯》主題:在《非神聖喜劇》和本評論中作為修飾語的“尤利西斯” - On desire and the she-wolf — la lupa — as the embodiment of negative desire, cupiditas

在欲望和母狼——拉盧帕——作為負面欲望的具現,貪婪 - First half of Inferno 1: mythic binaries in a visionary landscape

地獄篇第一部分:神話二元對立於一個富有遠見的景觀 - Second half of Inferno 1: arrival of Vergil/Virgilio and the introduction of history

地獄篇第一卷下半部分:維吉爾的到來及歷史的介紹 - The use of dialogue to build diegetic complexity and to construct character

使用對話來建立敘事複雜性和塑造角色 - Classical culture both in bono and in malo

古典文化無論在善與惡中 - A blueprint of the afterlife in three realms

三界來世的藍圖 - “Con lei ti lascerò nel mio partire” (Inf. 1.123): Dante’s ability to conjure real affect in real time

“Con lei ti lascerò nel mio partire” (Inf. 1.123): 但丁在實時中喚起真實情感的能力

[1] Inferno 1 and Inferno 2 are both introductory canti, although in quite different ways: Inferno 1 is more universal and world-historical in its focus, while Inferno 2 is more attentive to the plight and history — past and future — of one single man. The hero’s journey through Hell does not begin until Inferno 3. So what happens before we get to Inferno 3? What happens in Inferno 1 and Inferno 2?

[1] 地獄篇 1 和地獄篇 2 都是入門的詩章,雖然方式截然不同:地獄篇 1 的焦點更具普遍性和世界歷史性,而地獄篇 2 則更關注一個單獨人物的困境和歷史——過去和未來。英雄在地獄中的旅程直到地獄篇 3 才開始。那么在我們到達地獄篇 3 之前發生了什麼?在地獄篇 1 和地獄篇 2 中發生了什麼?

[2] In Inferno 1 and Inferno 2 Dante-poet is creating the premises that enable the subsequent action to occur. He is laying down the premises that enable the reader to suspend credibility and to “believe” in that action. Thus, the poet is already engaged in the Commedia’s great project of creating a virtual reality.

在《地獄篇》第一卷和第二卷中,詩人但丁正在創造使隨後的行動得以發生的前提。他正在奠定使讀者能夠暫時懷疑可信度並“相信”該行動的前提。因此,詩人已經參與了《神曲》偉大的項目,創造一個虛擬現實。

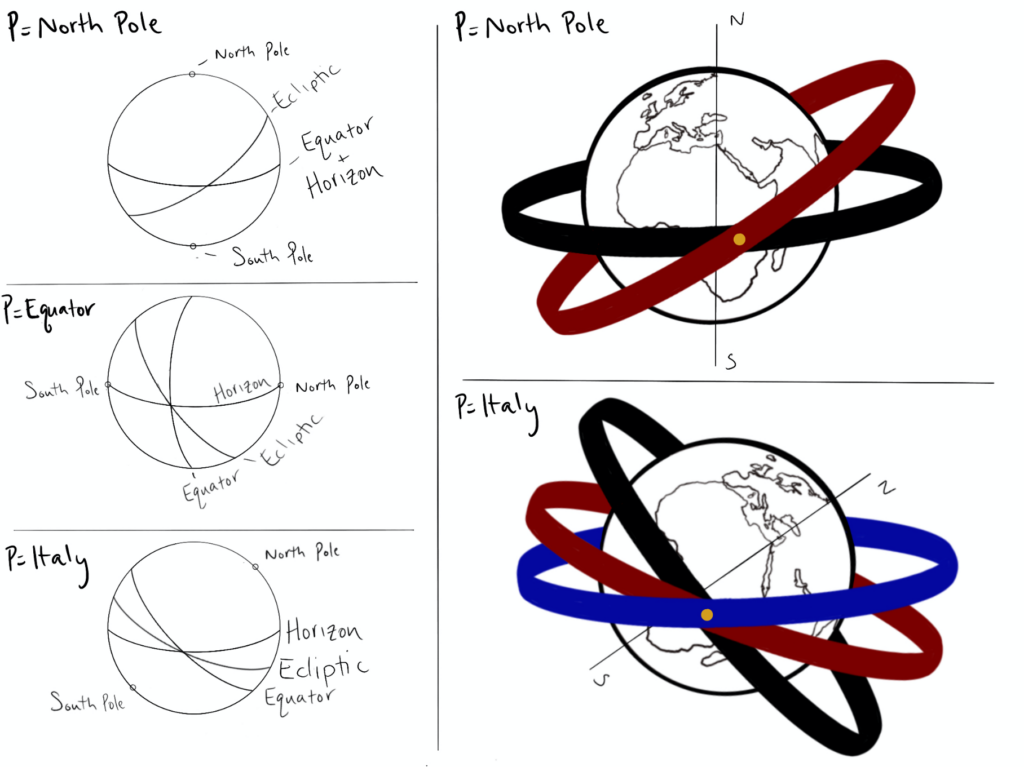

[3] Another way in which Dante sets about creating his possible world is by indicating the parameters of his universe, which he does by linking the rising sun to the original moment of creation: “’l sol montava ’n su con quelle stelle / ch’eran con lui quando l’amor divino / mosse di prima quelle cose belle” (the sun was rising now in fellowship / with the same stars that had escorted it / when Divine Love first moved those things of beauty [Inf. 1.38-40]). The sun is rising “with the same stars” that were with it when God first created stars and everything else. It was believed that creation occurred in springtime. Therefore, Dante is telling us that the the sun is in Aries — it is springtime. (See the astronomical diagram below by Louis Moffa.)

[3] 但丁創造他可能的世界的另一種方式是通過指示他宇宙的參數,他通過將升起的太陽與創造的原始時刻聯繫起來來做到這一點:“’l sol montava ’n su con quelle stelle / ch’eran con lui quando l’amor divino / mosse di prima quelle cose belle”(太陽現在在與它一起的同樣星星的陪伴下升起 / 當神聖的愛首次驅動那些美麗的事物時 [地獄 1.38-40])。太陽正在“與同樣的星星”一起升起,這些星星在上帝首次創造星星和其他一切時與它同在。人們相信創造發生在春天。因此,丹特告訴我們,太陽在白羊座——這是春天。(見下方路易斯·莫法的天文圖。)

[4] We note too that the ground of being is also the ground of aesthetics: God made cose belle — things of beauty. Moreover, this use of belle is the first occurrence of any form of the adjective “beautiful” in the Commedia. There is a cluster of first occurrences of forms of bello in Inferno 1-3: “cose belle” (Inf. 1.40), “lo bello stilo” (Inf. 1.87), “donna . . . bella” (Inf. 2.53), “bel monte” (Inf. 2.120), “i ciel . . . men belli” (Inf. 3.40).

[4] 我們也注意到存在的根基也是美學的根基:上帝創造了美麗的事物。此外,這裡使用的“美麗”是《神曲》中“美”的形容詞的首次出現。在《地獄篇》1-3 中,有一系列“美”的首次出現:“美麗的事物”(地獄 1.40),“美麗的風格”(地獄 1.87),“美麗的女人”(地獄 2.53),“美麗的山”(地獄 2.120),“天空中最美的”(地獄 3.40)。

[5] Inferno 1 features both the beauty of the universe (“cose belle”) and the beauty of Dante’s poetic style (“lo bello stilo”): in other words, the canto features being, that which is, and Dante’s poetry, that which represents being. The two — being and the representation of being — will go self-consciously in tandem throughout the Commedia. A term more familiar to literary critics than “being” is “reality”; thus, it is not surprising that reality and realism are themes that pulse through Dante Studies.

[5] 地獄篇第一章同時展現了宇宙的美(“cose belle”)和但丁詩歌風格的美(“lo bello stilo”):換句話說,這首詩歌展現了存在,即那個存在的事物,以及但丁的詩歌,即代表存在的事物。這兩者——存在和存在的表現——將在整部神曲中自覺地並行。對文學評論家來說,比“存在”更熟悉的術語是“現實”;因此,現實和現實主義成為但丁研究中脈動的主題並不令人驚訝。

[6] Inferno consists of 34 canti, Purgatorio of 33 canti, and Paradiso of 33 canti, making Inferno 1 the “extra” unit of text, as befits a canto that offers a prelude to the journey as a whole. Inferno 1 concludes with a schematic outline of the three regions of the afterlife: verses 114-117 describe Hell, verses 118-120 describe Purgatory, and verses 121-129 describe Paradise. Together, this section offers a blueprint of the entire journey, of all 100 canti of the poem. Therefore, when Dante wrote Inferno 1 he knew, at least in schematic terms, that the Commedia would comprise three regions, likely corresponding to three books.

[6] 《地獄》由 34 首詩組成,《煉獄》由 33 首詩組成,而《天堂》也由 33 首詩組成,使得《地獄》第一首成為“額外”的文本單位,正如一首為整個旅程提供序幕的詩所應有的。《地獄》第一首以對來世三個區域的示意圖結束:第 114-117 節描述地獄,第 118-120 節描述煉獄,第 121-129 節描述天堂。這一部分共同提供了整個旅程的藍圖,即詩的 100 首詩。因此,當但丁寫下《地獄》第一首時,他至少在示意上知道《神曲》將包括三個區域,可能對應於三本書。

* * *

[7] Ideas of the afterlife have histories, like all ideas. Dante has a place in the history of the imagining of the Christian afterlife, a place that can be traced and debated. Two Dantean signatures in the forging of his afterlife are the mixing of classical with Christian sources and of high with low culture:

[7] 來世的觀念有其歷史,就像所有觀念一樣。但丁在基督教來世的想像歷史中佔有一席之地,這一地位可以追溯和辯論。形成他來世的兩個但丁特徵是古典與基督教來源的混合以及高文化與低文化的交融:

Therefore, although Dante reflects the most informed theological thought on hell, he is certainly not constrained by it. Moving from the theological template, he widens the range of cultural resources available to him in two fundamental ways: one, he utilizes pagan sources as well as Christian ones; two, he does not limit his Christian sources to the high culture of theology. Thus, he explicitly borrows from such (high culture) pagan sources as Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, which he credits as a source for the structure of his hell, and Vergil’s underworld in Aeneid 6, various of whose characters and features he appropriates and transforms. But Dante’s hell also demonstrates clear links to the established popular iconography of hell and to popular cultural forms like sermons, visions, and the didactic poetry of vernacular predecessors such as Bonvesin da la Riva and Giacomino da Verona. As Alison Morgan correctly notes in Dante and the Medieval Other World, Dante ‘‘is the first Christian writer to combine the popular material with the theological and philosophical systems of his day’’ (“Medieval Multiculturalism and Dante’s Theology of Hell,” cited in Coordinated Reading, p. 103).

因此,儘管但丁反映了對地獄最具深度的神學思想,但他顯然並不受其限制。從神學範本出發,他以兩種基本方式擴大了可用的文化資源範圍:第一,他利用了異教來源以及基督教來源;第二,他並不將基督教來源限制於神學的高文化。因此,他明確地借鑒了如亞里士多德的《尼科馬可倫理學》這樣的(高文化)異教來源,並將其視為他地獄結構的來源,以及維吉爾在《埃涅阿斯紀》第六卷中的冥界,其中的各種角色和特徵他都加以借用和轉化。但丁的地獄也明顯與既定的地獄流行圖像以及如講道、異象和本土前輩如博恩維辛·達·拉·里瓦和賈科米諾·達·維羅納的教學詩等流行文化形式有著清晰的聯繫。正如艾莉森·摩根在《但丁與中世紀的另一個世界》中正確指出的,但丁“是第一位將流行材料與他所處時代的神學和哲學體系相結合的基督教作家”。

[8] The mixing of classical with Christian sources is a Dantean trait already established in the poem’s first verse. Here the pilgrim is lost in a dark wood at the midway point of life’s path, which is to say, at thirty-five years old. Very con veniently, Dante was born in 1265 and in 1300, the year that he stipulates for his afterlife journey, he was precisely thirty-five, midway through a lifespan of seventy years (see Psalm 90:10: “Our days may come to seventy years”)

[8] 將古典與基督教來源混合是但丁詩作中已確立的特徵。在這裡,朝聖者在生命旅程的中途,即三十五歲時,迷失在黑暗的森林中。非常巧合的是,但丁出生於 1265 年,而在 1300 年,即他所規定的來世旅程的年份,他恰好三十五歲,正處於七十年壽命的中途(見詩篇 90:10:“我們的年日如同七十年”)

[9] The poet has combined biblical and classical motifs to create a uniquely hybrid “middling” textuality. “Nel mezzo” marks a middle-point/meeting-point of cultural imbrication: “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita” (Midway upon the journey of our life [Inf. 1.1]) evokes, as critics have long noted, both biblical and classical precedents, both Isaiah 38:10 (“In the middle of my days I must depart”) and Horace’s injunction in Ars Poetica to commence a narrative “in medias res” (in the midst of things [Ars Poetica, 148]). The mid-point thus boasts both classical and biblical pedigrees.

詩人結合了聖經和古典主題,創造出一種獨特的混合“中庸”文本性。“Nel mezzo”標誌著文化交織的中點/交匯點:“Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita”(在我們生命的旅程中途[Inf. 1.1])喚起了,正如評論家們長期指出的,聖經和古典的先例,既有以賽亞書 38:10(“在我生命的中間我必須離去”)也有賀拉斯在《詩藝》中對敘事的要求,即在“中間事物”中開始敘述(在事物之中[詩藝,148])。因此,這個中點擁有古典和聖經的血統。

[10] To the above well-known intertexts for “Nel mezzo”, I will add two Aristotelian texts: the passage in the Physics where we find Aristotle’s discussion of time, and the passage in Nicomachean Ethics where we find his definition of virtue.

[10] 對於上述著名的“Nel mezzo”互文,我將添加兩段亞里士多德的文本:在《物理學》中我們找到亞里士多德對時間的討論,以及在《尼科馬科倫理學》中我們找到他對美德的定義。

[11] In the Physics, Aristotle describes time as “a kind of middle-point, uniting in itself both a beginning and an end, a beginning of future time and an end of past time” (Physics 8.1.251b18–26).[1] In his philosophical prose treatise, Convivio, written before the Inferno, circa 1304-1307, Dante shows that he is acquainted with Aristotle’s writings on time, citing the Physics as follows: “Lo tempo, secondo che dice Aristotile nel quarto de la Fisica, è ‘numero di movimento, secondo prima e poi’” (Time, according to Aristotle in the fourth book of the Physics, is “number of movement, according to before and after” [Conv. 4.2.6]).

[11] 在《物理學》中,亞里士多德將時間描述為「一種中點,將未來的開始和過去的結束統合在一起」(《物理學》8.1.251b18–26)。[1] 在他的哲學散文論文《宴會》中,這部作品寫於《地獄》之前,大約在 1304 年至 1307 年之間,丹特顯示他熟悉亞里士多德關於時間的著作,引用《物理學》如下:「根據亞里士多德在《物理學》第四卷所說,時間是‘運動的數量,根據之前和之後’」(《宴會》4.2.6)。

[12] When Dante begins the Commedia “Nel mezzo”, it is hard not to think of Aristotle’s definition of time as “a kind of middle-point” and to feel that the poet is alerting us to our existential being in time, also intrinsic to the opening metaphor of life as a path. As humans, we are ineluctably tethered to “number of motion, according to before and after”—to time.

[12] 當但丁在《神曲》中開始“在中間”時,很難不想到亞里士多德對時間的定義為“某種中點”,並感受到詩人正在提醒我們在時間中的存在,這也與生命作為一條道路的開場隱喻密切相關。作為人類,我們不可避免地與“運動的數量,根據之前和之後”相連——與時間相連。

[13] Now we turn to the second and more explicit Aristotelian resonance in the first verse of the poem, one built into the choice of the very word “mezzo”. Aristotle wrote on virtue as the mean between two vicious extremes in Nicomachean Ethics, Dante, by the time he came to write Inferno 1, had already meditated at length on the Ethics and on the Aristotelian concept of virtue. Indeed, in his canzone Le dolci rime, written circa 1294, long before the Inferno, Dante translates Aristotle from Latin into Italian, referring to the Aristotelian “mean” in Italian as “mezzo”: “Quest’è, secondo che l’Etica dice, / un abito eligente / lo qual dimora in mezzo solamente” (This is, as the Ethics states, a “habit of choosing which keeps steadily to the mean” [Le dolci rime, 85–87; trans. Foster-Boyde]). He returned to the same canzone roughly ten years later in Book 4 of the Convivio, which he devoted to the canzone Le dolci rime and to a discussion of Aristotle’s ethical system, in which virtue is the mean: the mezzo.

[13] 現在我們轉向詩的第一行中更明顯的亞里士多德共鳴,這是建立在“mezzo”這個詞的選擇上。亞里士多德在《尼科馬科倫理學》中寫到美德是兩個惡劣極端之間的中庸,當但丁在寫《地獄篇 1》時,他已經對倫理學和亞里士多德的美德概念進行了長時間的思考。事實上,在他約於 1294 年寫的歌曲《甜美的韻律》中,早於《地獄篇》,但丁將亞里士多德從拉丁文翻譯成意大利文,並將亞里士多德的“中庸”在意大利文中稱為“mezzo”: “Quest’è, secondo che l’Etica dice, / un abito eligente / lo qual dimora in mezzo solamente”(這是,正如倫理學所說的,“一種選擇的習慣,穩定地保持在中庸” [《甜美的韻律》,85–87;譯者:Foster-Boyde])。大約十年後,他在《宴會》中第 4 卷再次提到同一首歌曲,該卷專門討論《甜美的韻律》和亞里士多德的倫理體系,其中美德是中庸:mezzo。

[14] One of the themes of this commentary is the degree to which the Aristotelian idea of virtue as the mean carries over from the fourth book of the Convivio to permeate the deep structures of Dante’s thought. In other words, although Dante certainly resonates to Augustine and other dualist Christian thinkers on the topic of desire, as we shall discuss shortly, he does not keep his analysis within a binary structure, but opens it to the Aristotelian spectrum. It is important to grasp that Aristotle’s idea of the mezzo belongs within a unified and non-dualistic construction of human behavior.[2]

這段評論的一個主題是亞里士多德的美德作為中庸的觀念在《宴會》的第四卷中延續到但丁思想的深層結構的程度。換句話說,儘管但丁在欲望主題上確實與奧古斯丁和其他二元主義基督教思想家產生共鳴,正如我們稍後將討論的那樣,他並沒有將自己的分析局限於二元結構,而是將其開放到亞里士多德的光譜中。重要的是要理解,亞里士多德的中庸觀念屬於一個統一的、非二元的人的行為建構中。

[15] Both these Aristotelian understandings—of virtue as the mean and of time as a middle-point—inform the first verse of the Commedia. The word mezzo in the Commedia’s first verse is Aristotelian as well as biblical and Horatian. It resonates both to Aristotle on time, in the metaphysical dimension, and to Aristotle on virtue, in the moral-ethical sphere.

[15] 這兩種亞里士多德的理解——將美德視為中庸,將時間視為中點——影響了《神曲》的第一句。 《神曲》第一句中的“mezzo”一詞既是亞里士多德的,也是聖經和賀拉斯的。它在形而上學的維度上與亞里士多德的時間相呼應,在道德倫理的領域中與亞里士多德的美德相呼應。

* * *

[16] The metaphor “cammin di nostra vita”/“journey of our life” begins the work of conflating the journey of the poem with the existential and personal journeys through time and space that each of us on this planet experiences every day. As Dante had previously written in the Convivio, human life is a “new and never before traveled path”: “[il] nuovo e mai non fatto cammino di questa vita” (the new and never before traveled path of this life [Convivio 4.12.15]). The Commedia’s work of creating a virtual reality, of encouraging its readers to feel that they are journeying along with Dante, begins with the metaphor of life as a path on which we all walk. The walkers are plural and many, and each has her own path; in this sense the paths are many. But we all walk the cammino di questa vita: in this existential sense the path is one. The experience of life as a journey through time and space is an experience shared by all.

[16] 隱喻“cammin di nostra vita”/“我們生命的旅程”開始了將詩的旅程與我們每個人在這個星球上每天經歷的存在性和個人旅程融合在一起的工作。正如但丁在《宴會》中所寫的,人類的生活是一條“全新且從未走過的道路”: “[il] nuovo e mai non fatto cammino di questa vita”(這一生的新且從未走過的道路 [Convivio 4.12.15])。《神曲》創造虛擬現實的工作,鼓勵讀者感受到他們與但丁一同旅行,始於將生命比作我們都在行走的道路的隱喻。行走者是複數且眾多的,每個人都有自己的道路;在這個意義上,路徑是多樣的。但我們都在走這條“cammino di questa vita”:在這個存在的意義上,這條道路是唯一的。作為一段穿越時間和空間的旅程的生活體驗是所有人共同的體驗。

[17] The opening metaphor of the path, of the voyage by land, will shortly be enriched by the simile of a disastrous voyage by sea. The shipwrecked man who climbs from the watery deep to the shore is the first “Ulyssean” reference of the poem (Inf. 1.22-24). The mythic Greek hero Odysseus, Ulysses in Latin, as Dante encountered him in Vergil’s Aeneid and Cicero’s De Finibus and other Latin texts, is a prime reference point in the Commedia, as well as the featured soul of Inferno 26: Ulysses is the quintessential voyager who comes to perdition, who is lost at sea. As many have noted, Ulysses is Dante-pilgrim’s negative double. However, as my book The Undivine Comedy argues, Dante-poet becomes ever more transgressive and Ulyssean as the Commedia proceeds. From the point of view of the writing poet, Paradiso is the most transgressive — the most Ulyssean — part of the poem. The Ulyssean component of the Commedia is a major theme of The Undivine Comedy and of this Commento, and my usage of the epithet “Ulyssean” will be clarified as we proceed.

[17] 小路的開場隱喻,陸地的航行,將很快被海上災難性航行的比喻所豐富。從水深處爬上岸的船難者是詩中第一個“尤利西斯”的參考(地獄篇 1.22-24)。神話中的希臘英雄奧德修斯,拉丁文中的尤利西斯,正如但丁在維吉爾的《埃涅阿斯紀》和西塞羅的《論終極》等其他拉丁文文本中遇見的,是《神曲》的主要參考點,也是地獄篇第 26 章的主角:尤利西斯是典型的航行者,走向滅亡,迷失在海上。正如許多人所指出的,尤利西斯是但丁朝聖者的負面雙胞胎。然而,正如我在《非神曲》中所論述的,隨著《神曲》的進展,但丁詩人變得越來越越界和尤利西斯式。從寫作詩人的角度來看,《天堂篇》是詩中最具越界性——最尤利西斯式的部分。《神曲》的尤利西斯成分是《非神曲》和本評論的一個主要主題,我對“尤利西斯式”這一稱號的使用將在我們的討論中得到澄清。

[18] The premise of Dante’s journey is that, like Ulysses, he has lost his way: “ché la diritta via era smarrita” (for the straight way was lost [Inf. 1.3]). Moreover, he is not just passively lost; he has actively abandoned the true way: “la verace via abbandonai” (I abandoned the true path [Inf. 1.12]). However, he spies a way forward. He arrives at a hill whose shoulders are clothed by the rays of the sun, named in periphrasis as the planet that leads men straight by all paths:

[18] 但丁的旅程前提是,他像尤利西斯一樣迷失了方向:“ché la diritta via era smarrita”(因為正確的道路已經迷失 [Inf. 1.3])。此外,他不僅僅是被動地迷失;他主動放棄了真實的道路:“la verace via abbandonai”(我放棄了真實的道路 [Inf. 1.12])。然而,他看到了前進的道路。他來到一座山,山的肩膀被陽光的光芒所覆蓋,這座山以迂迴的方式被稱為引導人們沿著所有道路直行的行星:

Ma poi ch’i’ fui al piè d’un colle giunto, là dove terminava quella valle che m’avea di paura il cor compunto, guardai in alto, e vidi le sue spalle vestite già de’ raggi del pianeta che mena dritto altrui per ogne calle. (Inf. 1.13-18)

But when I’d reached the bottom of a hill— it rose along the boundary of the valley that had harassed my heart with so much fear— I looked on high and saw its shoulders clothed already by the rays of that same planet which serves to lead men straight along all roads.

[19] After resting, the protagonist sets out to climb the hill, “colle” in verse 13 (later called a mountain, in verse 77), whose heights are “dressed” in divine light. He attempts to climb the hill three times and three times he is repulsed and forced backward and downward, to perdition. The poet here creates a “stuttering” narrative texture of repeated “new beginnings” (see chapter 2 of Undivine Comedy for the concept of new beginnings and for the way they play out in the first canti of Inferno), thus giving narrative life to the bumpy and ever-impeded paths of our existential lives. The three beasts who block the pilgrim’s way grow ever more fearsome: the first is a leopard (lonza), then comes a lion (leone), and finally a she-wolf (lupa). Traditionally the three beasts have been identified with lust (lonza), pride (leone), and avarice (lupa).

[19] 在休息後,主角出發攀登詩句 13 中的“小山”(在詩句 77 中稱為山),其高度被神聖的光芒“裝飾”。他嘗試攀登這座小山三次,三次都被擊退,迫使他向後和向下退去,走向滅亡。詩人在這裡創造了一種“口吃”的敘事質感,重複的“新開始”(參見《非神曲》第 2 章中對新開始的概念及其在《地獄》首詩中的表現),從而賦予我們存在生活中崎嶇不平和不斷受阻的道路以敘事生命。阻擋朝聖者道路的三隻野獸變得越來越可怕:第一隻是豹子(lonza),然後是獅子(leone),最後是母狼(lupa)。傳統上,這三隻野獸被認為分別代表著慾望(lonza)、驕傲(leone)和貪婪(lupa)。

[20] Particularly important for the essential Dantean theme of desire as it will be unfolded throughout the Commedia is the lupa, who will be recalled in Purgatorio 20.10-12 for her “fame sanza fine cupa” (dark hunger without end; these verses are quoted in the long passage from page 110 of The Undivine Comedy cited in paragraph 24 below). The she-wolf goes beyond a narrow definition of avarice and embodies the negative polarity in the spectrum of desire: cupiditas.

[20] 對於整部《神曲》中將展開的基本但丁主題——欲望,特別重要的是那隻母狼,她將在《煉獄篇》20.10-12 中被提及,因為她的“fame sanza fine cupa”(無盡的黑暗渴望;這些詩句在下文第 24 段中引用的《非神曲》第 110 頁的長段落中提到)。母狼超越了對貪婪的狹隘定義,體現了欲望光譜中的負極性:貪求。

[21] Desire is defined in the Convivio as that which we lack: “ché nullo desidera quello che ha, ma quello che non ha, che è manifesto difetto” (for no one desires what he has, but what he does not have, which is manifest lack [Conv. 3.15.3]). Desire is defective, as I write in The Undivine Comedy:

[21] 渴望在《宴會》中被定義為我們所缺乏的東西:“ché nullo desidera quello che ha, ma quello che non ha, che è manifesto difetto”(因為沒有人渴望他所擁有的,而是渴望他所沒有的,這是明顯的缺失 [Conv. 3.15.3])。渴望是有缺陷的,正如我在《非神聖的喜劇》中所寫的:

Desire is defective, while the cessation of desire is happiness, beatitude, in a word perfection. Beatitude as spiritual autonomy — as emancipation from the new — is introduced as early as the Vita Nuova, where Dante learns to place his beatitudine not in Beatrice’s greeting, which can be removed (thus causing him to desire, to exist defectively), but in that which cannot fail him: “quello che non mi puote venire meno” (VN 18.4). Since nothing mortal can satisfy these conditions, we either learn from the failure of one object of desire to cease to desire mortal objects altogether, or we move forward along the path of life toward something else, something new. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 26)

欲望是有缺陷的,而欲望的停止是幸福、福祉,簡而言之就是完美。福祉作為精神自主——作為擺脫新事物的解放——早在《新生》中就已被引入,當時但丁學會將他的福祉放在不會被移除的事物上,而不是在貝阿特麗切的問候上(這會使他產生欲望,存在於缺陷中),而是放在“quello che non mi puote venire meno”(VN 18.4)上。由於沒有任何凡人事物能滿足這些條件,我們要麼從一個欲望對象的失敗中學會完全停止對凡人事物的渴望,要麼沿著生命的道路向其他事物邁進,向一些新的事物邁進。(《非神曲》,第 26 頁)

[22] The description of the lupa connotes desire as lack, for she eats and remains hungry, embodying Augustinian cupidity and lack of peace:

[22] 描述中的狼女暗示著渴望是一種缺乏,因為她吃了卻仍然感到飢餓,體現了奧古斯丁的貪婪和缺乏平靜:

The lupa of Inferno 1 illuminates the negative side of the basic human condition whereby disire è moto spiritale and recalls Augustine’s own reduction of all desire to spiritual motion, either in the form of “charity,” desire that moves toward God, or “cupidity,” desire that remains rooted in the flesh. As cupidity, our dark desire, the lupa is quintessentially without peace, “la bestia sanza pace” (Inf. 1.58). Her restlessness and insatiability denote unceasing spiritual motion, unceasing desire: heavy “with all longings” — “di tutte brame” (49) — her greedy craving is never filled, and after eating she is more hungry than before: “mai non empie la bramosa voglia, / e dopo ’l pasto ha più fame che pria” [Inf. 1.98-99]). Her limitless hunger is both caused by unsatisfied desire and creates the condition for ever less satisfaction, since, in Augustine’s words, “When vices have emptied the soul and led it to a kind of extreme hunger, it leaps into crimes by means of which impediments to the vices may be removed or the vices themselves sustained” (De Doctrina Christiana 3.10.16). When the “antica lupa” is recalled as an emblem of cupidity on purgatory’s terrace of avarice (again indicating the common ground that underlies all the sins of inordinate desire), her “hunger without end” is once more her distinguishing characteristic: “Maladetta sie tu, antica lupa, / che più che tutte l’altre bestie hai preda / per la tua fame sanza fine cupa!” (Cursed be you, ancient wolf, who more than all the other beasts have prey, because of your deep hunger without end! [Purg. 20.10-12]). (The Undivine Comedy, p. 110)

地獄第一章的狼女照亮了基本人性狀況的負面面向,其中欲望是靈魂的運動,並回想起奧古斯丁將所有欲望歸結為靈性運動的觀點,無論是以“慈愛”的形式,朝向上帝的欲望,還是以“貪婪”的形式,根植於肉體的欲望。作為貪婪,我們的黑暗欲望,狼女本質上是沒有平靜的,“無平靜的野獸”(地獄 1.58)。她的不安和無法滿足表明不斷的靈性運動,不斷的欲望:沉重地“承載著所有的渴望”——“di tutte brame”(49)——她貪婪的渴望永遠無法填滿,吃過之後她比之前更餓:“永遠無法滿足渴望,/ 吃過飯後比之前更餓”(地獄 1.98-99)。她無限的饑餓既是由於未滿足的欲望造成的,也創造了越來越少滿足的條件,因為,根據奧古斯丁的話,“當惡習使靈魂空虛並導致一種極端的饑餓時,它便通過犯罪來跳躍,藉此可以消除對惡習的障礙或維持惡習本身”(基督教教義 3.10.16)。 當“古老的狼”被喚起作為貪婪的象徵,位於煉獄的貪婪之台(再次指示所有過度欲望的罪惡之間的共同基礎),她“無盡的饑餓”再次成為她的特徵:“該詛咒你,古老的狼,/ 你比所有其他野獸更有獵物,/ 因為你那無盡的深沉饑餓!”(《非神曲》,第 20.10-12 頁)。 110)

[23] Desire is lack, but therefore it is also the imperative of forward motion, the “spiritual motion” in which we engage to fill the lack. This is precisely the definition of desire that Dante offers in Purgatorio 18: “disire, / ch’è moto spiritale” (desire, which is spiritual motion [Purg. 18.31–32]). Desire leads us astray, but desire also leads us to the good. How we negotiate our impulse of desire, whether we regulate it with our reason — these are the keys to our destiny. Desire for Dante is not wrong per se, but must always be controlled by reason, as he lets us know forcefully in Inferno 5. (Commento on Inferno 5)

[23] 慾望是缺乏,但因此它也是向前運動的必然性,即我們為了填補缺乏而參與的“精神運動”。這正是但丁在《煉獄篇》第 18 章中所提供的慾望定義:“disire, / ch’è moto spiritale”(慾望,即精神運動 [Purg. 18.31–32])。慾望使我們迷失,但慾望也引導我們走向善。 我們如何協商我們的慾望衝動,無論我們是否用理性來調節它——這些都是我們命運的關鍵。對於但丁來說,慾望本身並不是錯誤的,但必須始終受到理性的控制,正如他在《地獄篇》第 5 章中強烈告訴我們的那樣。(《地獄篇》第 5 章註解)

[24] Dante’s interest in the regulation of desire by reason is part of what leads him to value misura, the moderating force in the Aristotelian ethical scheme. Misura, a concept that Dante will first invoke in Inferno 7, is the behavior that keeps us “dwelling only at the mean” (Le dolci rime, 87).

但丁對理性調節欲望的興趣是他重視 misura 的部分原因,這是亞里士多德倫理體系中的調節力量。Misura 是一個但丁將在《地獄篇》第七章首次提到的概念,它是使我們“僅僅停留在中庸之處”的行為(《甜美的韻律》,87)。

* * *

[25] Throughout this reading of Inferno I use Italian “Virgilio” to refer to the character in Dante’s poem. In this way I distinguish the character “Virgilio” (invented by Dante Alighieri) from the historical person, Vergil, the Roman author of the Aeneid who lived from 70 BCE to 19 BCE. (On the reasons for my choice of spelling of “Vergil,” see Dante’s Poets, p. 207, n. 25.)

[25] 在這篇《地獄》閱讀中,我使用意大利文的“Virgilio”來指代但丁詩中的角色。這樣我就區分了角色“Virgilio”(由但丁·阿利吉耶里創造)和歷史人物維吉爾,這位生活在公元前 70 年至公元前 19 年的羅馬《埃涅阿斯紀》作者。(關於我選擇“Vergil”拼寫的原因,請參見《但丁的詩人》,第 207 頁,註釋 25。)

[26] The narrative structure of Inferno 1 makes the figure Virgilio a literally pivotal presence in the action of the first canto. Structurally and narratologically, Inferno 1 is a canto that divides into two parts: the part that precedes the arrival of Virgilio, and the part that follows the arrival of Virgilio. The first part of Inferno 1 takes place in an ambiguous surreal topography, one that is dream-like and uncanny, organized around mythic binaries: up/down, straight/crooked, light/dark, true/false, life/death. The actual landscape does not change until the entrance into Hell at the beginning of Inferno 3, but the narrative atmosphere, the poem’s tonality, shifts with the arrival of Virgilio in verse 62. His presence historicizes and grounds the text.

[26] 《地獄篇》第一章的敘事結構使得維吉里奧成為第一首詩行動中的一個字面上的關鍵存在。在結構和敘事學上,《地獄篇》第一章分為兩部分:維吉里奧到來之前的部分和維吉里奧到來之後的部分。《地獄篇》第一章的第一部分發生在一個模糊的超現實地形中,這個地形夢幻而詭異,圍繞著神話二元對立組織:上/下、直/彎、光/暗、真/假、生命/死亡。實際的景觀直到《地獄篇》第三章開始進入地獄時才會改變,但隨著維吉里奧在第 62 行的到來,敘事氛圍和詩的音調發生了變化。他的存在使文本具有歷史性並為其奠定基礎。

[27] In the first conversation between the pilgrim and Virgilio, Dante-poet moves his narrative from the mythic and visionary exordium of the poem (a the visionary “sleep” of verse 11) toward that mimetic and historical engagement with “reality” for which the Commedia is renowned.

在朝聖者與維吉爾的第一次對話中,丹特詩人將他的敘事從詩的神話和幻想開端(第 11 行的幻想“睡眠”)轉向與“現實”的模仿和歷史互動,這正是《神曲》所聞名的。

[28] Indeed, the suture marks that tie the mythic to the historical are not hidden, but left visible, rendered visible by a detail that is worth noting, although to my knowledge not picked up by the commentary tradition: the lupa is — remarkably, and quite unrealistically — present during the entire opening dialogue between Dante and Virgilio. What was Dante’s goal in writing this scene as he does? Why does he choose to construct the unrealistic overlap between the presence of the daunting lupa, so fearsome that she blocks all passage, all forward motion, and the arrival of the Roman poet?

[28] 確實,將神話與歷史聯繫起來的縫合痕跡並不隱藏,而是保持可見,這一細節值得注意,儘管據我所知,評論傳統並未提及:狼女在但丁與維吉爾的整個開場對話中——顯著且相當不現實地——一直存在。 但丁在這一場景中寫作的目的是什麼?他為什麼選擇構建這種不現實的重疊,即可怕的狼女的存在,令她阻擋所有通行、所有前進的動作,與羅馬詩人的到來之間的重疊?

[29] With complete lack of verisimilitude, the terrifying beast waits quietly and patiently during many tercets of conversation. The dialogue between Dante and Virgilio begins in verse 65, when Dante-protagonist calls out, beseeching pity of the unknown shade who has just appeared, and yet only in verse 88 does Dante finally ask the Roman poet for help. Twenty-six verses have thus elapsed from the beginning of their conversation until the pilgrim, in verse 88, finally points to the lupa and asks for succor:

[29] 完全缺乏真實感的可怕野獸在許多三行詩的對話中靜靜地耐心等待。當但丁主角在第 65 行呼喚,懇求剛出現的未知陰影施以憐憫時,與維吉利奧的對話開始了,然而直到第 88 行,但丁才終於向這位羅馬詩人求助。因此,從他們對話的開始到朝聖者在第 88 行最終指向母狼並請求救助,已經過去了二十六行詩。

Vedi la bestia per cu’ io mi volsi: aiutami da lei, famoso saggio, ch’ella mi fa tremar le vene e i polsi. (Inf. 1.88-90)

You see the beast that made me turn aside; help me, o famous sage, to stand against her, for she has made my blood and pulses shudder.

[30] Let us reconstruct the dialogue that occurs prior to the above request for assistance. Virgilio begins to speak in verse 67, and his first words embed his character in temporal and geographical specificity (at times resulting in curious anachronisms, like his reference to his family as “Lombard” in verse 68). In the phrase “Nacqui sub Julio” (I was born under Julius [Inf. 1.70]), Virgilio situates himself in the time of Julius Caesar (100–44 BCE), thus locating himself with precision in the flow of human history. He then announces that he was a poet and explains, by circumlocution, that he wrote the Aeneid (73-75). Virgilio at this point focuses on his interlocutor and asks Dante why he is going backwards rather than forwards. Why is he returning to the darkness whence he came?: “Ma tu perché ritorni a tanta noia?” (But why do you return to wretchedness? [Inf. 1.76]). Why isn’t he climbing the “delightful mountain” (a reference to the colle of verse 13) that is “the origin and cause of every joy”: “perché non sali il dilettoso monte / ch’è principio e cagion di tutta gioia?” (77-78).

[30] 讓我們重建在上述求助請求之前發生的對話。維吉利奧在第 67 行開始講話,他的第一句話將他的角色嵌入時間和地理的具體性中(有時導致奇特的年代錯誤,例如他在第 68 行提到他的家族為「倫巴第人」)。在「Nacqui sub Julio」(我出生於尤利烏斯之下 [Inf. 1.70])這句話中,維吉利奧將自己置於尤利烏斯·凱撒(公元前 100–44 年)的時代,從而精確地定位自己在人類歷史的流動中。然後他宣布自己是一位詩人,並通過迂迴的方式解釋他寫了《埃涅阿斯紀》 (73-75)。此時,維吉利奧專注於他的對話者,並問但丁為什麼他是向後而不是向前走。為什麼他要回到他來時的黑暗之中?:“Ma tu perché ritorni a tanta noia?”(但你為什麼要回到這麼痛苦的地方? [Inf. 1.76])。為什麼他不攀登那座「愉悅的山」(指第 13 行的山丘),那是「所有喜悅的起源和原因」:“perché non sali il dilettoso monte / ch’è principio e cagion di tutta gioia?”(77-78)。

[31] Dante-traveler does not answer these questions, although they offer the opportunity to address the presence of the she-wolf. In effect the pilgrim rejects the opportunity to beg for protection from the lupa. Why? Because he experiences overwhelming desire to focus on the identity of the shade whom he has just met.

[31] 但丁旅行者並未回答這些問題,儘管它們提供了機會來處理母狼的存在。事實上,朝聖者拒絕了向母狼乞求保護的機會。為什麼?因為他強烈渴望專注於他剛剛遇到的陰影的身份。

[32] Dante replies to the shade of the Roman poet by posing his own amazed question, which amounts to “Are you really Virgilio?”: “Or se’ tu quel Virgilio . . . ?” (And are you then that Vergil . . . ? [Inf. 1.79]). In the slippage between the question posed by Virgilio, which pertains to the canto’s major plot-line of Dante’s failure, fear, and distress, and the protagonist’s digressive reply, which opens a new plot-line regarding Dante’s overpowering love for Vergil and his poetry — a love that in the moment takes precedence even over seeking refuge from the lupa and being able to climb the mountain that leads to salvation — we learn something new about this poet. He adores Vergil’s poetry and classical antiquity. We also see how Dante-poet uses dialogue to generate new plot-lines and thus diegetic complexity. He also uses dialogue to construct character.

[32] 但丁對羅馬詩人影子的回應是提出他自己驚訝的問題,這相當於「你真的是維吉利奧嗎?」:“Or se’ tu quel Virgilio . . . ?”(那麼你就是那個維吉爾嗎 . . . ? [地獄 1.79])。在維吉利奧提出的問題與主角的離題回應之間的滑動中,前者涉及到詩篇的主要情節——但丁的失敗、恐懼和痛苦,而後者則開啟了一條新的情節線,關於但丁對維吉爾及其詩歌的壓倒性愛慕——這種愛在此刻甚至優先於尋求避難於狼和能夠攀登通往救贖的山——我們對這位詩人有了新的了解。他崇拜維吉爾的詩歌和古典古代。我們還看到但丁詩人如何利用對話來產生新的情節線,從而增加敘事的複雜性。他還利用對話來構建角色。

[33] Virgilio now explains figuratively the nature of the lupa and the threat that the beast poses: “e dopo ’l pasto ha più fame che pria” (when she has fed, she’s hungrier than before [Inf. 1.99]). We infer that the negative desire the lupa embodies is cupiditas, an ever-unsatisfied hunger and greed that can never be filled. The lupa is so fierce an impediment that the hill that she blocks cannot be climbed; in the next canto she is called precisely the beast “che del bel monte il corto andar ti tolse” (that barred the shortest way up the fair mountain [Inf. 2.120]). Unable to go directly upward, Dante must take a much longer route to the heights by traversing the three realms of the afterlife. Describing the three realms, Virgilio tells Dante that he will eventually come to a place where he must leave him and where another guide, an unnamed woman, will take his place: “con lei ti lascerò nel mio partire” (With her at my departure I will leave thee [Inf. 1.123]).

[33] 維吉里奧現在形象地解釋了狼女的本質以及這個野獸所帶來的威脅:“e dopo ’l pasto ha più fame che pria”(當她吃過後,她比之前更餓 [Inf. 1.99])。我們推斷,狼女所體現的負面欲望是貪婪,這是一種永遠無法滿足的飢餓和貪婪。狼女是一個如此兇猛的障礙,以至於她阻擋的山丘無法攀登;在下一首歌中,她被稱為“che del bel monte il corto andar ti tolse”(那阻礙了你通往美麗山丘的最短路徑 [Inf. 2.120])。無法直接向上攀登,丹特必須通過穿越三個來世的領域來走一條更長的路。維吉里奧描述這三個領域時告訴丹特,他最終會來到一個地方,在那裡他必須離開他,另一位導遊,一位未具名的女性,將取代他的位置:“con lei ti lascerò nel mio partire”(在我離開時我將把你留給她 [Inf. 1.123])。

[34] This verse, “con lei ti lascerò nel mio partire” (With her at my departure I will leave thee), is signally important: it provides a benchmark that the reader can use to measure Dante’s ability to conjure real affect in real time. Right now, in Inferno 1, Dante-protagonist (and mirroring him the reader) pays little attention to this announcement of Virgilio’s eventual departure. However, when that departure occurs in Purgatorio 30, much time and textual space later, the protagonist (and in my experience as a teacher, most readers) will be distraught, experiencing Virgilio’s “partire” as a personal abandonment. Between Inferno 1 and Purgatorio 30, therefore, Dante-poet convincingly and incrementally changes Dante-pilgrim from the figure we meet in Inferno 1 — a poetic enthusiast who is thrilled to meet the author of the Aeneid but does not care that Virgilio will ultimately leave him — to the man he is in Purgatorio 30: by then his sorrow at the loss of his father-guide is so great that it temporarily eclipses his joy at the arrival of his original lost beloved, Beatrice.

[34] 這句詩句「con lei ti lascerò nel mio partire」(在我離開時我將離開你)非常重要:它提供了一個基準,讀者可以用來衡量但丁在真實時間中喚起真實情感的能力。此時,在《地獄篇》第一章中,作為主角的但丁(以及與他相映的讀者)對維吉利奧最終離開的宣告並不太在意。然而,當這一離開在《淨界篇》第三十章中發生時,經過了很長的時間和文本空間,主角(根據我作為教師的經驗,大多數讀者)將感到痛苦,將維吉利奧的「離開」視為個人的拋棄。因此,在《地獄篇》第一章和《淨界篇》第三十章之間,但丁詩人令人信服且逐步地將但丁朝聖者從我們在《地獄篇》第一章中遇到的形象——一位對遇見《埃涅阿斯紀》作者感到興奮的詩歌愛好者,但不在乎維吉利奧最終會離開他——轉變為他在《淨界篇》第三十章中的樣子:到那時,他對失去父親導師的悲傷如此之大,以至於暫時掩蓋了他對原本失去的摯愛比阿特麗斯到來的喜悅。

[35] Let us return to the lovely interlude in which the pilgrim reacts with amazement to being in the presence of a poet whose work has been of seminal importance to him in his own poetic self-fashioning (Inf. 1.82-87). We readers, too, in mimetic reflection of the pilgrim, should be amazed: the guide chosen for this quintessentially Christian quest is the great author of the Latin epic of the founding of Rome. Through the creation of the character of Virgilio and the storyline that he devises for him, Dante-poet engages his deep feelings about classical antiquity, a major theme of this poem.

[35] 讓我們回到那段美妙的插曲,朝聖者對於能夠與一位對他自身詩歌塑造具有重要意義的詩人同在而感到驚訝(《神曲》1.82-87)。我們讀者也應該像朝聖者一樣感到驚訝:這個典型的基督教探索所選擇的導師是偉大的拉丁史詩《羅馬建國史》的作者。通過創造維吉里奧這個角色以及他為其設計的故事情節,詩人但丁表達了他對古典古代的深刻感受,這是詩中的一個主要主題。

[36] Dante’s feelings about classical culture are authentic and conflictual, not at all ironic. Lack of irony is indeed what the poet dramatizes in the pilgrim’s explosive and emotional and deflecting response to Virgilio’s initial questions about his failure to climb the mountain: “Or se’ tu quel Virgilio . . . ?” (Inf. 1.79). Dante’s adoration of classical culture is real: in historiographic terms, Dante’s veneration of classical culture certainly qualifies as an early form of humanism, as will be discussed in the Commento on Inferno 4. But, if Dante’s veneration of classical culture is real, so too is his concern about the non-Christianity of that culture. It is typical of Dante to present us with a paradoxical and challenging both/and, rather than with a simplistic either/or.

[36] 但丁對古典文化的感受是真實而矛盾的,完全沒有諷刺意味。缺乏諷刺正是詩人在朝聖者對維吉利奧最初關於他未能攀登山峰的問題的激烈、情感化和迴避的反應中所戲劇化的:“你是那個維吉利奧嗎 . . . ?”(地獄篇 1.79)。但丁對古典文化的崇拜是真實的:在歷史學的術語中,但丁對古典文化的尊崇無疑可以被視為人文主義的早期形式,這將在《地獄篇》第 4 章的註釋中討論。但是,如果但丁對古典文化的尊崇是真實的,那麼他對該文化非基督教特性的擔憂也是如此。這是但丁的典型風格,他呈現給我們的是一種矛盾而具挑戰性的兩者皆是,而不是簡單的二選一。

[37] Thus, Dante has his character Virgilio announce that he lived “in the time of the false and lying gods” (“nel tempo de li dèi falsi e bugiardi” [Inf. 1.72]), but he also makes clear his “great love” for the Roman poet: “O de li altri poeti onore e lume / vagliami ’l lungo studio e ’l grande amore / che m’ha fatto cercar lo tuo volume” (O light and honor of all other poets, / may my long study and the intense love / that made me search your volume serve me now [Inf. 1.82-84]). Both statements reflect genuine belief and genuine feeling: Dante does indeed consider Vergil to have lived in a time of false deities, and at the same time he does truly love and honor Vergil’s poetry. Dante’s love for the poet Vergil, which takes poetic form as the protagonist’s love for the character Virgilio, structures conflict and tension into the Commedia. In retrospect we understand that this conflict and tension are already present in the first canto.

[37] 因此,丹特讓他的角色維吉里奧宣稱他生活在“虛假和說謊的神明的時代”(“nel tempo de li dèi falsi e bugiardi” [Inf. 1.72]),但他也清楚表達了他對這位羅馬詩人的“偉大愛情”: “O de li altri poeti onore e lume / vagliami ’l lungo studio e ’l grande amore / che m’ha fatto cercar lo tuo volume”(哦,所有其他詩人的光榮與光輝,/ 願我漫長的學習和強烈的愛情 / 使我尋找你的著作的努力現在能夠幫助我 [Inf. 1.82-84])。這兩個陳述反映了真摯的信念和真摯的感情:丹特確實認為維吉爾生活在一個虛假的神明時代,同時他也真心愛著並尊重維吉爾的詩歌。丹特對詩人維吉爾的愛,通過主角對角色維吉里奧的愛的詩意形式,將衝突和緊張結構化進入《神曲》。回顧起來,我們明白這種衝突和緊張在第一首歌中已經存在。

[38] The Commedia will give us ample opportunity to ponder the novelty and significance of a Christian poet who chooses a Roman poet not only as his poetic model but also as a vehicle of his salvation. In Inferno 1 Dante stakes enormous claims for Virgilio, and hence for classical poetry. This he does through his usage of four key words: poeta, saggio, volume, and autore. In chapter 3 of Dante’s Poets, I trace these four words in the Commedia. The following passage focuses on volume and autore:

[38] 這部《神曲》將給我們充分的機會去思考一位基督教詩人選擇羅馬詩人作為他的詩歌典範以及他救贖的載體的創新性和重要性。在《地獄篇》第一章中,丹特對維吉利奧以及古典詩歌提出了巨大的主張。他通過使用四個關鍵詞來實現這一點:poeta、saggio、volume 和 autore。在丹特的《詩人》中第三章,我追溯了這四個詞在《神曲》中的使用。以下段落專注於 volume 和 autore:

As compared to poeta and saggio, terms that describe a trajectory or progression, volume and autore are used in only two contexts: in Inferno for Vergil, and in Paradiso for God. The transition is so immense that it both heightens Vergil, the only poet who is an autore and whose book is a volume, and shrinks him by comparison with that other autore, Who is God, and that other volume, which is God’s book (volume is used variously in the last canticle, but always with relation to texts “written by” God, for instance the book of the future, the book of justice, the universe gathered into one volume). Moreover, when God is termed an author, He is not “’l mio autore” (Inf. 1.85), but the “verace autore” (Par. 26.40). (Dante’s Poets, p. 268)

與描述軌跡或進程的術語 poeta 和 saggio 相比,volume 和 autore 僅在兩個上下文中使用:在《地獄》中指維吉爾,在《天堂》中指上帝。這一轉變是如此巨大,以至於它既提升了維吉爾,這位唯一的詩人同時也是 autore,且他的書是 volume,又使他在與那位其他 autore(即上帝)和那本其他 volume(即上帝的書)相比時顯得渺小(在最後的頌歌中,volume 的用法各異,但始終與“由”上帝“寫的”文本有關,例如未來之書、公正之書、宇宙匯聚成的一本書)。此外,當上帝被稱為作者時,他不是“’l mio autore”(《地獄》1.85),而是“verace autore”(《天堂》26.40)。

[39] While the words volume and autore are used only for Virgilio and God, the word poeta traces a poetic lineage in the Commedia. This genealogy leads to Dante himself, in a crescendo that moves from Vergil to Statius to Dante:

[39] 雖然“volume”和“autore”這兩個詞僅用於維吉利烏斯和上帝,但“poeta”這個詞在《神曲》中追溯了一條詩意的血脈。這條血脈通向但丁本人,形成一個從維吉利烏斯到斯塔提烏斯再到但丁的漸進過程:

If Statius replaces Vergil in Purgatorio 22 when he appropriates for himself (albeit in modified form) the name poeta, the final displacement is accomplished by Dante, when he becomes the only poeta of the last canticle, announcing in Paradiso 25 that he shall return as poet to Florence to receive the laurel crown. Although that hope was never fulfilled, the impact of the phrase “ritornerò poeta” remains undiminished at a textual level, since it reveals the arc Dante has inscribed into his poem through the restricted use of the word poeta: the poetic mantle passes from the classical poets, essentially Vergil, to a transitional poet, whose Christianity is disjunct from his poetic practice (and hence the verse in Purgatorio 22 with its neat caesura: “Per te poeta fui, per te cristiano” [73]), to the poet whose Christian faith is a sine qua non of his poetics. (Dante’s Poets, p. 269)

如果斯塔修斯在《炼狱篇》第 22 章中取代维吉尔,尽管以修改过的形式自称为“诗人”,那么最终的位移则由但丁完成,当他成为最后一首颂歌的唯一“诗人”,在《天堂篇》第 25 章中宣布他将作为诗人返回佛罗伦萨以接受月桂冠。尽管这个希望从未实现,“ritornerò poeta”这一短语在文本层面的影响依然未减,因为它揭示了但丁通过对“诗人”一词的有限使用所描绘的弧线:诗的外衣从古典诗人,基本上是维吉尔,转移到一个过渡性的诗人,他的基督教信仰与他的诗歌实践相脱节(因此在《炼狱篇》第 22 章中的那句整齐的停顿:“Per te poeta fui, per te cristiano” [73]),再到那个其基督教信仰是其诗学的必要条件的诗人。(《但丁的诗人》,第 269 页)

[40] The poetic genealogy that is inscribed into the Commedia reveals the arc of poetic history moving from Vergil to Statius to Dante. It is this arc that I attempt to capture in the sub-titles of chapter 3 of Dante’s Poets: “Vergil: Poeta fui” (“I was a poet”, citing Inf. 1.73), “Statius: Per te poeta fui” (“Through you I was a poet”, citing Purg. 22.73), and “Dante: ritornerò poeta” (“I shall return as poet”, citing Par. 25.8). This poetic genealogy, which is unfolded incrementally, works both to single out Vergil for special honor and ultimately to displace him.

[40] 在《神曲》中刻印的詩意家譜揭示了詩歌歷史的弧線,從維吉爾到斯塔提烏斯再到但丁。正是這條弧線,我試圖在但丁的《詩人》第三章的副標題中捕捉:“維吉爾:Poeta fui”(“我曾是一位詩人”,引用自《地獄篇》1.73),“斯塔提烏斯:Per te poeta fui”(“因為你我曾是一位詩人”,引用自《淨罪篇》22.73)和“但丁:ritornerò poeta”(“我將重返詩人身份”,引用自《天堂篇》25.8)。這條逐步展開的詩意家譜,既特別表彰維吉爾,又最終取代了他。

[41] The history that pierces the mythic penumbra of the Commedia’s overture is Roman history. The first historic moment of consequence that we encounter in this Christian poem belongs to classical antiquity, which is immediately sutured to contemporary Italy. Contemporary Italy is invoked in the “umile Italia” (106) for which Vergilian heroes and heroines gave their lives in the past, leading forward in an uninterrupted continuum:

[41] 刺穿《神曲》序曲神話半影的歷史是羅馬歷史。我們在這首基督教詩中遇到的第一個重要歷史時刻屬於古典時代,這與當代意大利立即相連。在“卑微的意大利”(106)中提到的當代意大利,是維吉爾的英雄和女英雄們在過去為之獻身的,並在一個不間斷的延續中向前推進:

Di quella umile Italia fia salute per cui morì la vergine Cammilla, Eurialo e Turno e Niso di ferute. (Inf. 1.106-8)

He will restore humble Italy for which the maid Camilla died of wounds, and Nisus, Turnus, and Euryalus.

[42] That “Italia” needs to be rescued again is clear in Dante’s apostrophe to contemporary “Italia” in Purgatorio 6. Dante depicts Roman history as crucially informing the present: from Roman history we move directly to that of contemporary “Italia” (106), as from Roman poetry (the Aeneid) we move directly to contemporary Italian poetry, Dante’s own “bello stilo che m’ha fatto onore” (the noble style that has honored me [87]).

[42] 那個“意大利”再次需要被拯救在但丁於《煉獄篇》第六章對當代“意大利”的呼喚中顯而易見。但丁描繪羅馬歷史對當前的關鍵影響:從羅馬歷史我們直接轉向當代“意大利”(106),正如從羅馬詩歌(《埃涅阿斯紀》)我們直接轉向當代意大利詩歌,但丁自己的“bello stilo che m’ha fatto onore”(使我榮耀的高貴風格)[87]。

* * *

[1] Aristotle here is referring to the moment, which he considers indistinguishable from time: ªNow since time cannot exist and is unthinkable apart from the moment, and the moment is a kind of middle-point, uniting as it does in itself both a beginning and an end, a beginning of future time and an end of past time, it follows that there must always be time: for the extremity of the last period of time that we take must be found in some moment, since time contains no point of contact for us except in the moment. Therefore, since the moment is both a beginning and an end, there must always be time on both sides of itº (Physics 8.1.251b18-26; in the translation of R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye, in The Basic Works of Aristotle, ed. Richard McKeon [New York: Random House, 1941]).

[1] 亞里士多德在這裡提到的時刻,他認為這與時間無法區分:ª既然時間無法存在,並且無法在沒有時刻的情況下思考,而時刻是一種中點,因為它在自身中結合了開始和結束,未來時間的開始和過去時間的結束,因此必須總是有時間:因為我們所取的最後一段時間的極限必須在某個時刻中找到,因為時間對我們來說除了在時刻中沒有接觸點。因此,既然時刻既是開始又是結束,那麼在它的兩側必須總是有時間º(物理學 8.1.251b18-26;翻譯自 R. P. Hardie 和 R. K. Gaye,收錄於理查德·麥基翁編輯的《亞里士多德基本著作》,[紐約:隨機屋,1941])。

[2] On this topic, see my essay “Aristotle’s Mezzo, Courtly Misura, and Dante’s Canzone Le dolci rime”, cited in Coordinated Reading. For further elaboration of this belief system, see in this commentary the chapters on Inferno 5, Inferno 7, and Inferno 11.

[2] 在這個主題上,請參見我的文章「亞里士多德的中庸、宮廷的度量,以及但丁的歌曲《甜美的韻律》」,該文章在《協調閱讀》中被引用。欲進一步闡述這一信仰體系,請參見本評論中的《地獄》第 5 章、第 7 章和第 11 章。